Item

Chris Delvin Oral History, 2021/05/07

Title (Dublin Core)

Chris Delvin Oral History, 2021/05/07

Description (Dublin Core)

Chris Delvin is the RN perioperative manager at the Marshfield Clinic in Eau Claire. In this interview, Chris discusses the effects of the pandemic on his clinic and how he and his staff responded by converting a surgical clinic into a negative flow covid unit and doubling the number of beds they could handle. He talks not only about work but also about how the pandemic has transformed his home and spiritual life. Matt Schneider also joins midway through and offers his perspectives on how Chris managed the situation and contributed to helping protect his community.

Recording Date (Dublin Core)

Creator (Dublin Core)

Contributor (Dublin Core)

Partner (Dublin Core)

Controlled Vocabulary (Dublin Core)

Curator's Tags (Omeka Classic)

Collection (Dublin Core)

Curatorial Notes (Dublin Core)

Date Submitted (Dublin Core)

12/22/2021

Date Modified (Dublin Core)

05/21/2023

Date Created (Dublin Core)

05/07/2021

Interviewer (Bibliographic Ontology)

Bennett Running

Interviewee (Bibliographic Ontology)

Chris Delvin

Location (Omeka Classic)

54701

Altoona

Wisconsin

United States of America

Format (Dublin Core)

Audio

Language (Dublin Core)

English

Access Rights (Dublin Core)

05/07/2021

Duration (Omeka Classic)

00:53:37

abstract (Bibliographic Ontology)

Chris Delvin is the RN perioperative manager at the Marshfield Clinic in Eau Claire. In this interview, Chris discusses the effects of the pandemic on his clinic and how he and his staff responded by converting a surgical clinic into a negative flow covid unit and doubling the number of beds they could handle. He talks not only about work but also about how the pandemic has transformed his home and spiritual life. Matt Schneider also joins midway through and offers his perspectives on how Chris managed the situation and contributed to helping protect his community.

Transcription (Omeka Classic)

Bennett Running 0:05

But does it say recording for you?

Chris Delvin 0:09

Yes.

BR 0:10

Okay. So my name is Bennett Running. I'm a student at the University of Eau Claire, Wisconsin, the date is May 7 2021. And the time is currently 9:07. There have been 32,356,034 confirmed cases of COVID-19 in the United States and 576,238 deaths as a result, there have been 601,603 confirmed cases of COVID-19 II Wisconsin, and 6,877 deaths as a result. Currently, 32.8% of the US population has been fully vaccinated against COVID-19. What is your name? And do you mind sharing your demographic information with us?

CD 1:05

Yeah, my name is Chris Dublin. I'm an RN perioperative manager in Eau Claire, Wisconsin of Marshfield Clinic Health System.

BR 1:15

Thank you, what are the primary things you do on a day to day basis?

CD 1:22

I oversee all operations from a perioperative operational and procedural aspect of surgical services here. And also, I'm in control of the staffing and financial and growth opportunities for patient care in the procedural and surgical areas.

BR 1:46

Where do you live? And what is it like to live?

CD 1:50

I live in the Eau Claire area actually a resident of Altoona. It's a it's a nice, smaller community more of like a little of a suburb of Eau Claire. And it's kind of a nice regional setting close to the cities and not too far from Madison. So it's a nice centralized location in northern Wisconsin.

BR 2:17

What issues most concerns you have up to COVID-19

CD 2:26

Most of the issues came because you're trying to react to something in which you which was ever changing, it was such a fluid situation. That, you know, historically, everything in medicine throughout my career and many others is that you, you have a plan, you've seen it before. And you kind of have an idea of how to deal with it. And with COVID, we, they came in so strong and fierce that that we had to really kind of put up a ton of walls out of the gate, because we didn't know we didn't know how to test we didn't know how to treat, we didn't know what was going to work or what didn't work, we had no historical knowledge of this disease process and this virus. So you know, it really it really made us change. And then we would learn something new the following day. And we would have to, again, change the way that we were managing it. So it was really that that many folks and many opinions were brought into the fight against COVID-19. And then you tried to sort out the relevance and all of those thoughts.

BR 3:29

What was it like trying to sift through all of the different information and like daily updates from the CDC? Was it tough to implement the new changes that came out so quickly?

CD 3:41

It was, it wasn't as tough to sift through the recommendations. The recommendations came out from the CDC pretty straightforward. Again, you had to stay on it on a day to day basis there. You know, there's teams of folks that are constantly watching that from an infection prevention standpoint, and, and things like that, where they can give guidance and advice. The hardest part about that is the communication in which you get it out to you know, 1000s of staff members to make sure that everybody understands what the system has agreed to do, not to not to unsimilar from any other health system is, is you can make one recommendation, but you need to make sure that everybody else understands it and is able to follow it and then has the tools in which to complete that new objective.

BR 4:25

How has your job changed since the start of the pandemic?

CD 4:30

So, you know, when I was dealing, you know, my normal job is around perioperative services and operations that way and when the COVID pandemic came in, you know, and we had, we had our incident command set up and then I became more of an operational chief leader for that, essentially running the, the COVID unit. So I went out of procedural in surgical and into more of an inpatient care setting mainly because we were able to utilize a different, a different area within our hospital and, and I had the ability to in the honor to take over that that unit and really make it work.

BR 5:12

So in the email that I received from Matt Schnieder, it said that you helped set up and convert an area into a COVID. Like, Ward, can you tell me a little bit about that?

CD 5:25

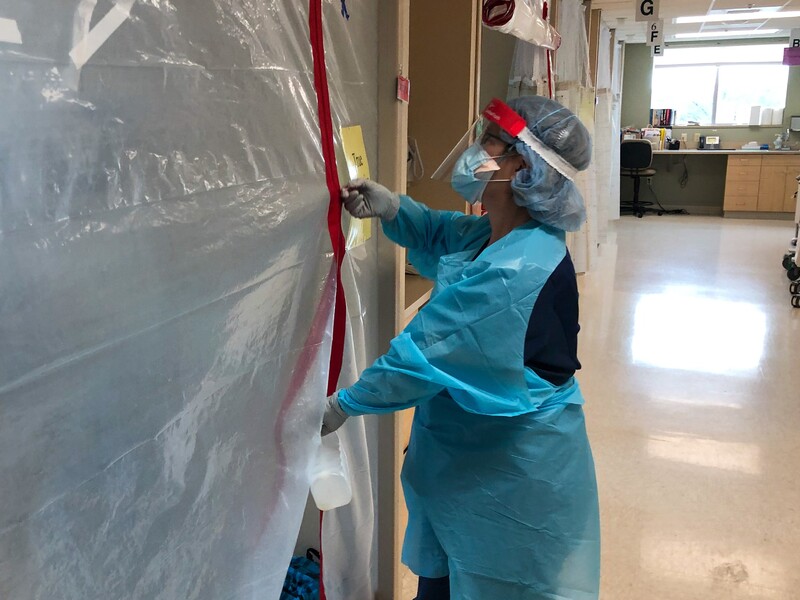

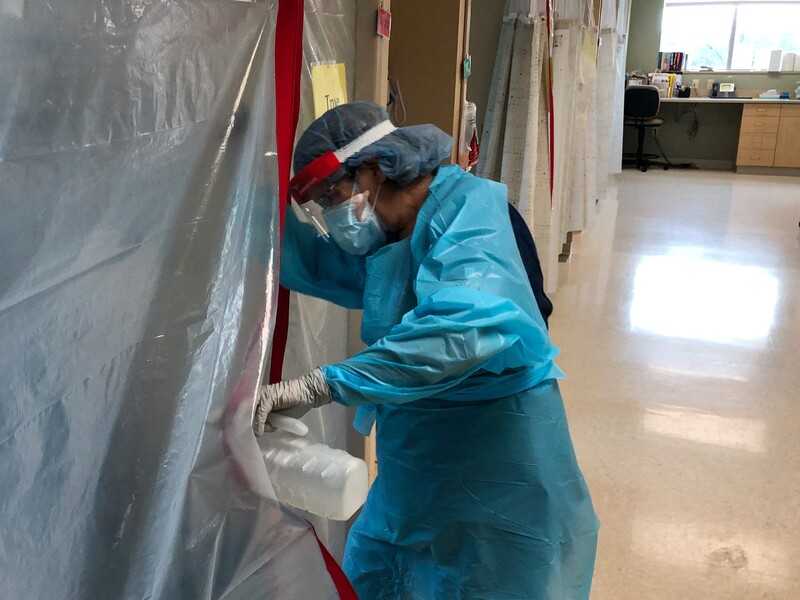

Sure, so what we took was our outpatient surgical department. So we have preoperative and post operative beds along with some operating rooms. And the conversion that we made was because because nationally, we had to, we had to pull back on surgicals, and start to do only emergent cases, because we didn't really know how the virus was going to spread. And we didn't know how to do effective testing, I was unable to use that to the use that location. So what we did was understanding that in a pre op and post operative setting, we have tools like oxygen and suction, and we have beds and bays in which we can use and then we have ways to run ventilators and you know, to be able to segregate our patients a bit, we converted that area into basically a negative pressure area by sealing it off, and then and then changing our ventilation to make sure that we we could put anybody with COVID positive diagnoses in there and be in that negative pressure setting because as you probably know, by now, the aerosol generating procedures is what is what creates COVID into an airborne precaution need. So we really can't have patients who need those aerosol generating procedures to be around other patients who don't have COVID. That's how that's the fastest way for it to spread.

BR 6:53

What was it like trying to staff this in the in the middle of a pandemic

CD 7:01

It was very, it was very difficult because we essentially you're taking, you're taking a staffing plan that's for 100% of your beds, effectively, right, and then we increased it by 30% or 40%. Right? So it's very difficult because you need to find those, those individuals with that skill set and that credential. But additionally, you also need to find the ones that have the skill set in which to do that. So it's not just that you need CNA as an RN, or pharmacy techs or housekeeping, but you need those folks to have the skills to actually be able to do the work, right. So if if COVID pandemic comes out, and most patients are ACU or acute care needs and or ICU intensive care needs, those nurses are in short supply. Additionally, staffing is a nightmare when we're normally you can come to work with a headache, and fight through your shift as anybody would do with any job when COVID sets in one of the symptoms of COVID is a headache. So now I'm down a staff member who otherwise might just have a headache, but we have to rule out COVID. So you're you're losing people for reasons and otherwise you would never lose for a day or two. So staffing became very, very difficult to fill those gaps. And really, our staff and the people around us were, you know, kind of came out of the woodwork to do what it took to get to get through that.

BR 8:30

Can you give me a rough estimate of how many patients have been treated at your medical center?

CD 8:37

Oh, that'sa great question. First of all, how many came through there.

BR 8:41

I put you on the spot here.

CD 8:43

Yeah. I just I don't want to come so far off the cuff. If, you know, over the course of all COVID all admit to the COVID unit 75 to 100.

BR 9:07

What was it like seeing those patients?

CD 9:12

It was it was interesting. COVID is is a unique virus. It was it was very difficult because you'd see one person who who had a lighter and more manageable version but needed some respite, you know, a little bit of respiratory help or a little little tune up, if you will, to help cover the gap and but otherwise very comfortable. And the next patient was very, very critical and really struggling, needing some more life sustaining interventions. So it was very difficult to it's very difficult not just for the patients, the ones that could talk would let you know that they're lonely and the ones who couldn't talk. You you knew that their families were lonely because we weren't able to let any visitors in for the sake of the transmission of disease. So it's just unlike anything we've ever had. Where, where you're not able to visit or see or understand what's happening with your loved one. Additionally, for the patients who can talk, communicate, and are mobile, they also want their family to be able to come visit them. So it's a it's a very lonely setting a very isolated setting, which we haven't experienced before by actually having to segregate these patients.

BR 10:31

What was it like trying to communicate with the families of people you were taking care of?

CD 10:40

It was hard. I mean, you really have to bank on your therapeutic communication. You know, we have teams with pastoral care, social services, palliative care, and our care case managers, that that are very good at coaching staff who, who may or may not have, you know, that higher level skill set to communicate with them. It's, it's very difficult to in any setting, ICU is the same way, you know, on a day to day basis pick us as the same way, you know, either the same way, it's very difficult to try to stay on a positive note, if you know, the outcome may not be great. So you try to instill hope, but not give false truths. Trying to explain what's happening with a loved one, but not actually knowing enough about the disease to understand the total progression of what's going to happen, is tough to give an outlook. Well, what do you think's going to happen? I don't know. Because I haven't seen. Here's what I think's going on right now. And here's what we're doing because of it is more the theory for treatment there. We did eventually, as the, as the year went on, understand more about how it was going to trend but out of the gate, it was very difficult to have those conversations and then try to maintain honesty, throughout throughout that letting them know, I want to give you answers. I just may not have them right now.

BR 12:00

It sounds pretty difficult not knowing what is actually happening to a person but still trying to care for.

CD 12:08

Exactly.

BR 12:11

Moving on from your employment to more of your like, family and household life? How is COVID-19 affected you and your family's day to day lives?

CD 12:24

Well, my wife and I are both nurses. So we worked through the pandemic, however, we have three kids, and they weren't unable to go to school. So childcare and management that way was difficult. My wife was furloughed for a little bit, much like many other people. And, you know, we had to wear the budget differently that way. We couldn't see family, you know, and you know, I guess it brought, I would say it brought a closeness to our family network. But it was hard to be separate from the rest of the world for a while.

BR 13:09

Did you have concerns working in a COVID Ward? And bringing that home to your family?

CD 13:17

That's a great question. I will let you know what I tell a lot of folks. We're fortunate in healthcare, right? So yes, I'm exposed closer to the known disease than then you are. But to give an analogy, you would go into Walmart or a gas station, wearing your mask and you try to stay away from people and then you go home. You don't know how many folks here around that have COVID or may not have COVID or any other disease for that matter. And then you go home, I know that I'm around them. But I'm also have the benefit of having the proper precautions. And the right supplies to do my job. I had a papper, I had gowns, I had gloves. I had negative pressure ventilation, I had everything set up for myself to stay safe. And then I was able to change my clothes and and we had processes set up so that when I left here, I was at the least amount of risk. So I felt I felt confident going home. Knowing that I used all those proper precautions, then I trust the system as I always have. And those things worked. Yeah, I trusted that. However, that being said, the caveat to that is what if PPE becomes a shortage. I did not have to experience that. We did monitoring of our supplies to make sure that we didn't run short. We tried to find ways in which to conserve, but much like the news set around the country. I in our local setting, I did not experience a shortage of PBE we always had enough to get by and stay safe

BR 15:02

That's great. How are you managing the day to day activities of your household?

CD 15:13

Currently, right now, my kids go four days a week to school, they're back to four days a week, and they still wear masks everywhere they go. But as far as, as far as segregation goes, we've definitely loosened the reins around what I would call our, our house in our neighborhood, you know, many people are vaccinated now where it's not as concerning, and we follow the CDC recommendations as best we can to, to make sure that we're doing the best for everybody around us. So right now are my are my kids that everybody else tired of the masks? Sure. But I really do believe that we've seen the effects of what good good hygiene and, and masking can do. And that's evidenced by the, you know, the reduced flu season and things like that, that, you know, if we stay a little bit cleaner, and we wash a little bit more, you know, we can do some good things. So and then the vaccines obviously, coming out, is very, very helpful for that herd immunity.

BR 16:15

It really, really is. How does the COVID-19 outbreak affect your communities be like your church club that your kids are in? Anything like that.

CD 16:31

Yes. So you know, that's a great example, when you think of church we have never had, we've never had a closed down church before, we have a very large community in our church. And with, you know, 1000s of people kind of coming through the door every day, to not actually be able to go there, they've done more outside services. And we actually, they've actually got very heavily into the multimedia online version of that, which, you know, is a great thing and tell you the truth, we find it more convenient for those times in which we do have other obligations that we can't avoid, to be able to attend. So what I say that we attend more often because it's virtual Sure. I think that we realized with school, my daughter's school, they had a snow day, but they didn't call it a snow day they'd had it or work from home day, because they were so used to doing online virtual schooling, that it wasn't a day that you're not in school, it's a day that you're just going to work from home and they know they can pull that off now. So many things have gone virtual, much like telehealth, in medicine that are they're leaning on heavily noticing that actually, it's it's very effective, and, and also cost effective for a lot of folks. So there's been some very good changes that we identified from the COVID pandemic. It's not it's not all, you know, sadness and, and things like that, but, but we learned a lot of things that are, you know, going to continue on going forward.

BR 18:02

How have your children adapted to the part in time or part in school and part online?

CD 18:11

You know, we are we're a fortunate family, my kids, sort of like that multimedia, I think it's very helpful that multimedia is such a big part of the youth life these days, so that they're used to looking at a screen talking to their friends on FaceTime and things like that. So, so honestly, they, they missed their friends, but they didn't miss getting up for the bus. So, you know, there's there's the good and the bad. But but they did they did fine. I think, I think that they would have maybe advanced just a hair more in their classes, they've they've all done very well, at least in our family. But do I think that they're a little bit more teacher, one on one contact, that that classroom focus that you get, versus maybe a few home distractions here and there. They probably would have done better in the school setting, and I'm sure they will going forward. But but they managed, they all knew what they were doing. And they're anywhere they're 12, 10 or 12, 10, and 7. So they, they were able to focus enough to get all their work done every day.

BR 19:14

How are people around you responding to the covid 19 pandemic?

CD 19:22

I feel that you really have to look at each person and each family as individuals. I can say there's any word from people still, you know, not wanting to be around other people and we respect that that they want to segregate and still work on 9 to 5's and, and and lockdown and there's there's other folks that you know, take the the non mandated or this the state reduction, a mandate of masking the other way and and they felt this they don't have to they don't want to and I think really you just have to not judge it. Just let other people do what what they think is right and, and just maintain your own? So how do I think other people responding? I think they respond as individuals going off their own ethics values and what they believe. And you know what, I'm doing the same, but I just don't judge anybody for what, what they think they should do.

BR 20:17

Have you seen any people around you change their opinions over the course of the pandemic?

CD 20:25

Yes, I think that I think that the emotions, the highs and lows of emotions, especially when it comes to, you know, a lot of this wasn't just Health and Health and Human safety. But a lot of it was financial, financially driven opinions. And what I did notice with a lot of folks was, you know, the furloughs was tough. When people weren't able to go to work, that was very difficult. And some people However, some other walks of life, with the, with the unemployment going up in the in the guaranteed additional, you know, they had those $600 stipends, and things like that they came out, some people were, were actually furloughed making more money on furlough than they were at their job, depending on your type of job. So, you know, there was there was a lot of financial emotions out there of I can't make it day to day. And, and please don't bring me back to work, you know, I'm doing better right now. So, but also that creates animosity between people too, right? Because, you know, here it was. And I'm sure any other employer would say the same you furlough somebody, and they're really bummed about it, and you feel really bad about it. And then they came up with the unemployment. So now they're doing okay, but now we're starting to loosen the restrictions. So now you need them to come back to work. And that also causes animosity, because now you're calling somebody back, and it becomes why me, not them. You know, I need my job. And then the, you know, and then the unemployment bonus went away. And then it's, well, now I want to come back to work. So you just have to understand that people's, you know, people's checkbook, was a big driver in what they wanted to hear from the way the COVID pandemic was going. And, you know, it's not as bad as it was, we should all be at work, or always terrible, you know, they need to support us financially this way, the government needs to do this. But it's all your personal situation, I think that really makes your emotions sway in such a way.

BR 22:27

Has COVID-19 changed your relationships with family and friends and the community?

CD 22:35

No, I don't think so. I think if anything change would have been for the positive knowing that you really saw I really saw here and I'm very fortunate for that 99% of the people were trying to do the right thing. And they were trying to figure out any way to help you know, I put out a thing when COVID first started. We put out a request for masks, right. And when there was a nationwide peepee shortage, and the amount of boxes 1000s and 1000s of masks and things that we got from folks, people coming, coming up with ideas to make specialized gowns or eye shields and things like that it was just really amazing to watch everybody in the community come together with with options to make us be safe and successful. I really was very impressed with I always say in times of crisis, people pulled together and they throw they set aside all their personal biases.

BR 23:39

Was that a one time community drive to get PP? Or did you guys do that multiple times?

CD 23:46

It went on for quite a while until until honestly, most of the general public right away it was a big deal because we had enough for our staff but we didn't have enough for patients but we needed patients to come in if they were going to need to come into the building we needed them to have masks, we didn't have enough for the staff and for the patients to give each patient who comes in for you know, say an hour to a mask and then they leave and we have to discard it. So the donations really came from when like you for example you would come to the clinic I'm sorry, I don't have a mask we use we gave you one of the donated masks to you and that way when you left you would have one as time went on with COVID and face coverings became mandatory everywhere you know as long as I do everywhere you go now everybody's got a mask so we just we just didn't need it anymore. But we needed it right away we didn't have any way to keep everyone safe and ourselves as well. So yes, as the need went down we stopped quote needing those donations. Because you can pick up a box now at Walmart if you need

BR 24:45

Yeah.

CD 24:48

Hi Matt I'm on with Bennett.

Matt Schneider 24:51

You are? Okay. I just he's given me a lecture about how interviews are only conducted one on one and I'm not invited. So I guess I just want to get up in your ear to be just very careful and cautious.

CD 25:02

He's on speaker with you and me.

MS 25:05

Okay. Bennett.

BR 25:07

Hi.

MS 25:09

Bennett. Are you familiar with HIPAA?

BR 25:12

Not particularly.

MS 25:15

Yeah, okay, we healthcare systems are required to abide by patient privacy, federal laws and laws are violated. Both you and our institution and Chris, as an individual could face some civil and criminal penalties basically. So that my reason for just wanting to be able to sit in is just to make sure those, you know, no lines across Chris is an experienced pro and I trust him. But sometimes you want to get rolling on telling a story. So that that's the reason why I want to be a part of this is I'm sure you're not aware of that. I was certain you weren't aware of those rules. So that's why.

BR 25:57

Sorry I had no idea. Sorry.

CD 25:59

No, it's all good. We haven't shared anything. Anything specific only generalized ideas.

MS 26:05

Perfect. Perfect. I trust you. But Mr. Mr. Running here...

CD 26:15

No, you're good. Go ahead, Bennett. I'll just leave you on speaker there, Matt.

BR 26:20

I can certainly send you the full transcript of the full interview. Before I submit it, of the 20 minutes that we did previously. Just so there's no..

CD 26:37

Yeah, it would be really nice. That'd be great. But yeah, so far, so good. So keep on rolling.

BR 26:46

Have anybody you know, got sick during the COVID-19 outbreak, and what was your experience in responding to their cities?

CD 26:54

You know, I have, I have known a lot of individuals for, you know, personally, and, you know, by by proxy. And, you know, the acuity definitely varied. Some, some of my, you know, family and friends got very, you know, got very ill, we have had some, some known folks, which in our familial community, pass away, and we've had others who tested positive and didn't even know they had it. So that's, that's what's really interesting about about this, you know, viral progression is, you just are not sure how it's going to hit each individual, I'll say I found this disease interesting. Because you could have one person in the family are two people in a family be positive, and the other three, they live together and eat together every day, be negative. So it's just such a unique scenario on why I'm interested to see study 10 years down the road of, of, you know, was there other? Was there other factors in which I have that maybe my wife didn't have, you know, and unfortunately, neither one of us have had COVID. But, you know, what, what are those things going to be that say, Oh, well, we now know that if you had this factor, you were more susceptible to that. So it's just interesting.

BR 28:17

Has your mental health been affected by the pandemic?

CD 28:26

I think there was times you know, in the, in the heat of the COVID pandemic, you know, where, where the communication and the amount of change and the adaptability that we needed to portray every day. It just got wearing, because, right, when you felt like you got settled, and you had good communication, and we were really doing all the right things, things would change a little bit. And you'd kind of go back to the drawing board, and that was okay, but you're kind of one foot in the pond, and one foot out of the pond in that was the thing is you just kept trying to do the next right thing. So yeah, mentally it was wearing I didn't ever get, I wouldn't say I would never got depressed. But frustrated from time to time. Sure. Only because our hearts in the right place, though. You want to do the best care and you're trying to do the best care. And then you kind of get a little curveball again. And so you go with that. And, you know, you do that over and over. And at some point, you're just thinking, my goodness, we could all use a little break. And you know, right now I got to tell you, we were we're doing we're doing pretty good. So we're feeling like we can breathe free air a little bit more now. So that's great.

BR 29:39

Would you say that's the general experience of those healthcare providers in general? Or do you think overall, there was a different experience?

CD 29:49

I think it depends on your setting. And the way that you deal with these experiences and some of this loss You know, everybody kind of takes it takes it a little bit differently, that's such a, that's going to be such an individualized reaction to the COVID pandemic, as you've heard before, glass half full glass half empty, you know, one person might say, you know, I lost a patient today, and the next person might say, I saved for. So it's always going to be your your outlook on it, that you, you did the best you could with this, the skills and the abilities that you had at the time. And and then you just have to accept the outcomes after that. So I would say that we everybody, I can't speak for the whole country, everybody did the best they could somebody saw 1000 deaths, and somebody may not have ever seen a death, obviously, they would each react completely different than the other one. It's just going to be so independent. On your experience. I will say that my experience, although it was it was happy and sad, and frustrating and interesting, all at the same time. That you just won't forget it, you know, but I can't say that. I can't say that the whole thing was a total loss at all, I think that we did a very good job for our community with what we could work with.

BR 31:18

Were you was your clinic involved? Like did it converting to giving out vaccines? Or is it still a COVID word?

CD 31:29

We are we are able to treat patients with COVID here. But we also are able to serve the community and our patients with with vaccines, we do get our allotment much like many other facilities. Yep. So we get vaccines every day.

BR 31:46

Have you received any pushback for providing vaccines?

CD 31:52

Not that I've heard. I think that's been a pretty positive thing that we're offering the community, I haven't heard any negative feedback for giving vaccine.

MS 32:00

I was I'll chime in on that one there is there's kind of a continual buzz in the community, anti vaxxers. And folks who are not interested in getting it, but I don't believe directly to my knowledge. And that's kind of my role. We've not gotten any direct negative pushback from people. As a matter of fact, we're really proud of the fact that 99.2% of our physicians have gotten this vaccine, and those who haven't. There's a reason.

BR 32:33

Have anyone, you know, had questions and concerns about the vaccine?

CD 32:41

Yeah, I think that there's, you know, there's always I really dislike the word skeptics, but those who get hesitant about, you know, things that they read there, there's a lot of misinformation, things that, you know, I think that people don't understand sometimes a lot of times in articles, they're they're meant to persuade you a certain way. And, you know, you believe in what you believe in, and there's some people that pre pre COVID, weren't vaccinators, and they're not going to be now. And I think that, you know, what, those those unfortunate issues that they had with the Johnson and Johnson vaccine, or, or even somebody who is a vaccine, a vaccine promoter would say, right, but I don't actually know what happens with this vaccine. 20 years down the line, you know, I get the flu shot, because we've had the flu shot forever, I get the the MMR shot, because everybody gets the MMR shot, and it's never caught, you know, it doesn't seem to cause an issue. But I think there's some hesitancy with that, yeah, that we, you know, we came out with this rather quickly, and and it's helping save millions of lives. But I think that it's appropriate for somebody to maybe have that question in the back of their head to say, but, you know, how does this affect me 20 years down the line? Sure. But those who have those strong opinions, usually let it be known. And, you know, I would say that the grand majority of folks are very supportive of vaccines, in my experience,

BR 34:09

What have been your primary sources of news during the pandemic?

CD 34:15

To be quite honest, I stick with just the the I try to, I personally, try to stick with the CDC guidelines, and really read up on what they're saying, you know, and FDA reports. I definitely stay away from the larger networks. They just, in my opinion, have a tendency to be a little bit biased one way or the other, but and I just want to know what the actual you know, as a medical professional, I want to know what the actual data says. And really, the only way for me to get that is to is to read it straight from the source and that way it's not manipulated or, or twisted just a little bit to make me believe one way or the other. So I really try to stay away from those but that's just because I personally believe in you know, it's tested, and it's read. And you know, it's coming from the folks which I put my trust in. And I put my trust in the FDA and the CDC, then that's what I go with, you know, and then we support our systems decisions for the way that we're handling that here. We do that as a system, system initiative system direction. And then we all you know, we do have the ability to chime in with our anything that we might know or understand a little bit differently. So

BR 35:27

Have your new sources change the pandemic, if you rely more on the CDC, or how's your news habits change?

CD 35:42

Is that aimed at me or Matt?

BR 35:45

Chris.

CD 35:47

Can you say it again?

BR 35:49

Has your sources of news changed with the pandemic, more on the CDC than you did before?

CD 36:02

No, I mean, I just had to take the real time data that I see, I can't say that I've changed my sources. I've just tried to rely on the national the national data that's put out through the CDC and what their recommendations are, and then trying to figure out, you know, how does that work with our current operation? How can we achieve the objective or the goal which they've set out? Because it's not always black and white. Is it's an it's an idea, or a recommendation? And then you say, Okay, how can we most closely resemble what they're trying to say here?

MS 36:40

When the when this all sort of started rolling out last March and April, when it really started getting intense. CDC guidelines were coming out three or four times a day. And so folks on the front line like Chris, we're having to continually adjust based on, you know, kind of as new information was learned about how the virus transmits or, you know, the reality, all that kind of stuff. So it's, it was interesting to see how that data off, it's fair to say this, Chris, but I think we kind of fortunate to really tune in to the CDC, we always have been to the guidance that they put out. But I think because it was such an intense thing and such a major global issue, and that things were changing so rapidly, we had to tune in more than we ever had in the past. That's a fair statement. You think, Chris?

CD 37:30

Yeah.

BR 37:35

What do you think are important issues the media is not or may be covering, and should be covered?

CD 37:49

I don't think it's so much what, you know what issues are important or not important? I feel that I feel that media, a bit tries to take, they try to find a voice that will be loud and strong in one in one aspect of their beliefs, and then they're able to run with it. So they may put out that a mask mandate is appropriate. But in the next turn, they'll interview somebody who wants to tell you 11 reasons why it's not appropriate. And I think sometimes for me, I would I would prefer it to just be, you know, what, what's the recommendation and why? And, you know, and then just trust that, but but I think a lot of it just happens to be you know, I don't know, what do they used to call that ratings driven, the more shock factor you can get or what so there's, there's a lot of people that just want their voice to be heard. But I do notice there's a lot of irrelevance and what a lot of people are saying, again, another reason why I just I kind of try to avoid the news, because I'm not really getting great information. I'm just giving more opinion. I think that's a great way to say like get more opinions on the news and they get actual information.

BR 39:16

But do you think there's a problem with misinformation in the media?

CD 39:25

Yes, and no, I mean, look, you know, we could we could have that discussion outside of here. But you know, for the sources of the interview, or the purpose of the interview, I would say that misinformation, probably not omission of information. Sure. So I can I can tell you, you know, whatever I want as long as I don't tell you what I don't want to hear. So it looks like my opinion is very good one, right. So I know I'm being very vague with you because I don't want to like point out anything that's not recommended, but by telling you 11 reasons why you shouldn't wear a comment or you know, you shouldn't wear masks, but I don't tell you 11 reasons why you should wear masks, then I guess I'm kind of being one sided. So I would say it's more omission of information than wrong information.

BR 40:15

How have the local leaders and state government officials in your community responded to the output?

CD 40:25

Honestly, I thought that our community did very well, I'm I, I have to make an I statement here, because not everybody will believe but I think that the state has tried to do a very good job, containing it, pushing out the vaccines helping with PPE giving resources where they need to, I think they've done a very good job trying to, you know, battle, I don't want to have a political conversation I never do. There's, there's folks on both sides of that wall that that want different things. But I think as far as the state, I have felt living in Wisconsin that I was supported, and that they had my best health interests in mind. And then I think that locally here to the city of Eau Claire and, and the health care facilities, and we have a lot of them here in Eau Claire, really pulled together to do the to do the best thing they could during this pandemic, I thought that everybody did a really good job supporting our community.

BR 41:18

Do you think there's anything that officials could have done differently to respond to the pandemic?

CD 41:31

You know, I guess I would have, you know, hindsight being 2020, I guess, you know, there's only there's only what you what could you have done more of, so we did, you know, mobile testing labs, but where they may be a little bit slower than they could have been? Sure. But at the same time, you know, they're trying to try to mobilize hundreds 1000s of people and, and, and get people out of the woodwork to get, you know, onside testing and rapid testing and which tests are appropriate. So, you know, I think that, that more localized testing during that time would have helped people maybe get tested quicker. And therefore, we could have responded to it a little bit quicker versus them waiting till they got real sick and then come in. So maybe, you know, a little bit more preventative care, or those early sign calls with, with more accurate and faster testing out of the gate, but really, here in the Eau Claire region, it was well handled it never so far knock on wood, it never got to a point where I felt, why why aren't we doing enough? I felt that the community kept up. And in every aspect that I needed to

MS 42:52

Bennett I will answer that I was part of the community wide, t's called joint command. So there's, you know, basically every all health entities, public health, anybody who really had a part to play in our community's response to this, which also kind of tied back to the state in the federal folks. I was involved with that starting. The first meeting happened, the second week in February, where we started kind of putting our heads together and kind of trying to look at the look at what's coming, and how do we respond and whatnot, instead of put a meeting with federal officials and providing recommendations on resource allocation. And one of the things that I think we discovered through this process, there really was an inadequate supply of the federal government keeps something called a strategic reserve. In this particular case, protective equipment was a real issue early on. And fortunately, Marshfield clinic and other large health systems have their own set of reserves, in case there's a supply chain issue, or something comes up. But because there was such a high global demand, and most of those are so critical to our care of highly virulent patients. That really wasn't an issue. They created a lot of strain on the system, and it took the supply chain well into late summer, early fall, to catch up to the point of having adequate than N95s and face masks and everything that we needed to really appropriately care for some patients that the standard we expect. So that's it. That was I think one thing that is such unique need to our community, if there was a federal thing and a global thing. We never, you know, as much as you try to anticipate everything the end of the day fully anticipated. What would happen if there was that kind of the demand or crushing, critical supplies? We also ran, you know, there's certain meds that were really tough to get ahold of and I don't want to get too far into your world, Chris, but there's a medicine called propofol, which is to make people think If they're having to be innovative, and they're uncomfortable, and they're struggling and whatnot, you give them that medicine to make them more comfortable. So they don't really miss they are aware of what's going on. And there was there was a global crush on medicine too. We were very lucky to have some very great pharmacists who get ahead of curve and get enough to get us in our patients cared for, and I know some hospitals to not have that. And that creates real challenges for their patients. Do you have anything else Chris, along those lines, that were challenges?

CD 45:33

No, I don't think so.

MS 45:39

We learned I think that that's the big thing, I think, and Chris again, I don't want to jump too far, you can feel sorry for doing this. But we Marshfield clinics as a hospital, we're not even three years old. And so I think going through the process of opening a new hospital, you know, to learn how to how to kind of operate in an urgent way, when things kind of came around, I'm going to toot and I did this in the original email about Chris. But Chris really took the lead on recognizing and they'll be, andI don't know, Chris, if you remember that meeting, when we all got together down in the administrative conference room that we just started spitballing, how are we gonna take care of these patients, and Chris really took the lead. And I think it was a matter of 48 hours, 72 hours, maybe they go from spitballing, conceptualizing what this COVID unit would look like to having it essentially up and ready for our first wave of patients should that surge calmness as early as we thought it might. So we're fortunate to have somebody like Chris. And then we were also fortunate, I think, to have a team that was very used to working together, you know, emergent situations, to be able to respond. Again, going back to the to the joint group that we were part of at the community level, we were the first ones to have our COVID unit up and ready to rock and roll. And we actually we at the time, were a 44 bed hospital. There were different tiers to the surge. But I think if we were to search all the way out at some level, Chris, tell me what, what the final number would have been of what we could have cared for having the staffing supplies in space. If we really got pushed, how many people could be taken care of if we had to?

CD 47:17

You know, honestly, we would have been in the in the 80s range, with staffing provided.

MS 47:25

First doubling up our capacity, which that's that's impressive.

CD 47:29

Yeah, no, that's building a second hospital basically.

BR 47:35

That's a very large expansion of care.

MS 47:41

Doing it in hours, and we can put it together in hours. But...

BR 47:43

Yeah I can only imagine.

MS 47:47

Chris, you are my hero.

CD 47:52

Heh we have a great team, my co partner, Lean Bolsinger. And, and everybody around us really, really killed it. And it was very impressive to watch. Everyone worked so fluidly. I mean, you know, everybody knows the ideas guy, but it's not just my hand doing it, you know?

BR 48:10

Has the pandemic brought you're, like staff together closer, like, more knit as a team?

CD 48:18

I would say 100%. Yes, we had folks that that worked in specialties and areas that came out of the woodwork and saying, Hey, I used to work in that I have that experience. And I think really what that did was it made us lean on folks that that you might have seen in the cafeteria didn't really know what they do. And now you are working hand in hand with them. And elbows to elbows, and and really gaining that trust in them. But now ultimately, you're also now when we're back in our what we would call the regular jobs or doing our original duties. You know, you talk to him on the phone, you understand. That's your colleague, but you know, the more the person instead of a role, you know, and I think that that's a big deal. Because a lot of times we pass people in the hallway, and you're friendly and cordial, and you know about where they work, but you don't know them. And I think that this drew everyone together very well.

BR 49:11

Has your experience transformed how you think about your family, your friends and community, your work? And in what ways?

CD 49:19

You know, it does, it's it's unique, you know, it's kind of like, kind of like a reset button, you know, back to the basics, if you will. So all the negative things about COVID What happened to my family? I said in our in our experience, we got closer, you know, we weren't we're traveling to the ball field every day and you know, going out to eat and or to friend's house and all this stuff. And it became you know, became more about the family vibe, and it's me and my wife and my kids. They don't sometimes I think, I think maybe that was a reset button to get back to the basics of you know, just enjoying each other's company. The, you know, we could evidence that by looking at the retail stores that there's no It was very difficult to find outdoors equipment, and things like that, because everybody was camping and fishing and, you know, doing these recreations because it's the only thing you could do all the bikes got sold, you know, and maybe that maybe that was really good for the world in that part, you know, that, that we all kind of got back to things a little bit of the simple life. So yeah, I'd say I've noticed that with a lot of folks. A lot of people enjoying the camping life and outdoors things now. So.

BR 50:29

So knowing what you know, now, what do you think that individuals, communities, governments need to keep in mind for the future?

CD 50:42

I think that pre planning preventative, you know, that, if it happens, what are we going to do? You know, it's a everything's kind of a up business thought, right? And if that happens, what will we do with you know, and I think that that was a, that was a big deal. With this, I think that's where we saw a lot of the drug in the PPE shortage was, you know, just not thinking about that not not that anyone was being malicious, and saying, you know, that'll never happen to us. But, but honestly, what if it did, did anybody really think that through, you know, and so, I think that, I think that we have ways in which Americans and the government and everybody can see that this is what we could do on a national level to pull everyone together if we needed to, it's a big deal, you know, it's a positive thing. And I'm kind of a positive thinker as it is. So I think that folks can realize, yeah, you can wear a mask for 18 months and not pass away, in or you can stay at home, and, and enjoy your family and not have to be involved in every single event out there. And, and from a governmental standpoint, you know, you can put out recommendations to the public. And yes, you're going to have some folks that, that push back, and that's just part of the natural progression. But you know, most people are gonna say, All right, let's pull together, let's do this, you know, you see it, you see it all the way from your household, to your community, to the statewide and the nationally, that, that we can pull together and get a lot of really, really cool things done, saw the whole world pulled together on this one trying to figure out a way to, to help stop it. That's a big deal. You know. So it's very interesting.

BR 52:19

Well that was all my questions. Thank you so much for giving this interview.

CD 52:25

Yeah, I appreciate it. And you know, I do have a question for you. Oh, how did it affect you? And you know, your, your student and, and son and all these other things, you know, how did how did you pull through?

BR 52:40

Um, similar experience to you, like if I brought my family, not just my nuclear family, but like my aunts and uncles closer together than I imagined we would ever be there. It was sort of strange to be getting closer to people. I mean, not physically, but like, emotionally closer to people through a pandemic.

CD 53:04

Absolutely, absolutely. Well, I know that I appreciate the interview. And I, you know, these words, obviously, and our talks will go on for a long time, and people keep reflecting on this 2020 situation. So yeah, appreciate you taking the time to talk with me and Matt and, and yeah, shoot me that email.

BR 53:27

All right I will.

CD 53:28

Yeah. And we'll talk next time.

BR 53:29

Awesome.

CD 53:32

Thank you. thank Matt.

MS 53:33

Thank you guys. Take care guys.

CD 53:35

Yeah bye.

But does it say recording for you?

Chris Delvin 0:09

Yes.

BR 0:10

Okay. So my name is Bennett Running. I'm a student at the University of Eau Claire, Wisconsin, the date is May 7 2021. And the time is currently 9:07. There have been 32,356,034 confirmed cases of COVID-19 in the United States and 576,238 deaths as a result, there have been 601,603 confirmed cases of COVID-19 II Wisconsin, and 6,877 deaths as a result. Currently, 32.8% of the US population has been fully vaccinated against COVID-19. What is your name? And do you mind sharing your demographic information with us?

CD 1:05

Yeah, my name is Chris Dublin. I'm an RN perioperative manager in Eau Claire, Wisconsin of Marshfield Clinic Health System.

BR 1:15

Thank you, what are the primary things you do on a day to day basis?

CD 1:22

I oversee all operations from a perioperative operational and procedural aspect of surgical services here. And also, I'm in control of the staffing and financial and growth opportunities for patient care in the procedural and surgical areas.

BR 1:46

Where do you live? And what is it like to live?

CD 1:50

I live in the Eau Claire area actually a resident of Altoona. It's a it's a nice, smaller community more of like a little of a suburb of Eau Claire. And it's kind of a nice regional setting close to the cities and not too far from Madison. So it's a nice centralized location in northern Wisconsin.

BR 2:17

What issues most concerns you have up to COVID-19

CD 2:26

Most of the issues came because you're trying to react to something in which you which was ever changing, it was such a fluid situation. That, you know, historically, everything in medicine throughout my career and many others is that you, you have a plan, you've seen it before. And you kind of have an idea of how to deal with it. And with COVID, we, they came in so strong and fierce that that we had to really kind of put up a ton of walls out of the gate, because we didn't know we didn't know how to test we didn't know how to treat, we didn't know what was going to work or what didn't work, we had no historical knowledge of this disease process and this virus. So you know, it really it really made us change. And then we would learn something new the following day. And we would have to, again, change the way that we were managing it. So it was really that that many folks and many opinions were brought into the fight against COVID-19. And then you tried to sort out the relevance and all of those thoughts.

BR 3:29

What was it like trying to sift through all of the different information and like daily updates from the CDC? Was it tough to implement the new changes that came out so quickly?

CD 3:41

It was, it wasn't as tough to sift through the recommendations. The recommendations came out from the CDC pretty straightforward. Again, you had to stay on it on a day to day basis there. You know, there's teams of folks that are constantly watching that from an infection prevention standpoint, and, and things like that, where they can give guidance and advice. The hardest part about that is the communication in which you get it out to you know, 1000s of staff members to make sure that everybody understands what the system has agreed to do, not to not to unsimilar from any other health system is, is you can make one recommendation, but you need to make sure that everybody else understands it and is able to follow it and then has the tools in which to complete that new objective.

BR 4:25

How has your job changed since the start of the pandemic?

CD 4:30

So, you know, when I was dealing, you know, my normal job is around perioperative services and operations that way and when the COVID pandemic came in, you know, and we had, we had our incident command set up and then I became more of an operational chief leader for that, essentially running the, the COVID unit. So I went out of procedural in surgical and into more of an inpatient care setting mainly because we were able to utilize a different, a different area within our hospital and, and I had the ability to in the honor to take over that that unit and really make it work.

BR 5:12

So in the email that I received from Matt Schnieder, it said that you helped set up and convert an area into a COVID. Like, Ward, can you tell me a little bit about that?

CD 5:25

Sure, so what we took was our outpatient surgical department. So we have preoperative and post operative beds along with some operating rooms. And the conversion that we made was because because nationally, we had to, we had to pull back on surgicals, and start to do only emergent cases, because we didn't really know how the virus was going to spread. And we didn't know how to do effective testing, I was unable to use that to the use that location. So what we did was understanding that in a pre op and post operative setting, we have tools like oxygen and suction, and we have beds and bays in which we can use and then we have ways to run ventilators and you know, to be able to segregate our patients a bit, we converted that area into basically a negative pressure area by sealing it off, and then and then changing our ventilation to make sure that we we could put anybody with COVID positive diagnoses in there and be in that negative pressure setting because as you probably know, by now, the aerosol generating procedures is what is what creates COVID into an airborne precaution need. So we really can't have patients who need those aerosol generating procedures to be around other patients who don't have COVID. That's how that's the fastest way for it to spread.

BR 6:53

What was it like trying to staff this in the in the middle of a pandemic

CD 7:01

It was very, it was very difficult because we essentially you're taking, you're taking a staffing plan that's for 100% of your beds, effectively, right, and then we increased it by 30% or 40%. Right? So it's very difficult because you need to find those, those individuals with that skill set and that credential. But additionally, you also need to find the ones that have the skill set in which to do that. So it's not just that you need CNA as an RN, or pharmacy techs or housekeeping, but you need those folks to have the skills to actually be able to do the work, right. So if if COVID pandemic comes out, and most patients are ACU or acute care needs and or ICU intensive care needs, those nurses are in short supply. Additionally, staffing is a nightmare when we're normally you can come to work with a headache, and fight through your shift as anybody would do with any job when COVID sets in one of the symptoms of COVID is a headache. So now I'm down a staff member who otherwise might just have a headache, but we have to rule out COVID. So you're you're losing people for reasons and otherwise you would never lose for a day or two. So staffing became very, very difficult to fill those gaps. And really, our staff and the people around us were, you know, kind of came out of the woodwork to do what it took to get to get through that.

BR 8:30

Can you give me a rough estimate of how many patients have been treated at your medical center?

CD 8:37

Oh, that'sa great question. First of all, how many came through there.

BR 8:41

I put you on the spot here.

CD 8:43

Yeah. I just I don't want to come so far off the cuff. If, you know, over the course of all COVID all admit to the COVID unit 75 to 100.

BR 9:07

What was it like seeing those patients?

CD 9:12

It was it was interesting. COVID is is a unique virus. It was it was very difficult because you'd see one person who who had a lighter and more manageable version but needed some respite, you know, a little bit of respiratory help or a little little tune up, if you will, to help cover the gap and but otherwise very comfortable. And the next patient was very, very critical and really struggling, needing some more life sustaining interventions. So it was very difficult to it's very difficult not just for the patients, the ones that could talk would let you know that they're lonely and the ones who couldn't talk. You you knew that their families were lonely because we weren't able to let any visitors in for the sake of the transmission of disease. So it's just unlike anything we've ever had. Where, where you're not able to visit or see or understand what's happening with your loved one. Additionally, for the patients who can talk, communicate, and are mobile, they also want their family to be able to come visit them. So it's a it's a very lonely setting a very isolated setting, which we haven't experienced before by actually having to segregate these patients.

BR 10:31

What was it like trying to communicate with the families of people you were taking care of?

CD 10:40

It was hard. I mean, you really have to bank on your therapeutic communication. You know, we have teams with pastoral care, social services, palliative care, and our care case managers, that that are very good at coaching staff who, who may or may not have, you know, that higher level skill set to communicate with them. It's, it's very difficult to in any setting, ICU is the same way, you know, on a day to day basis pick us as the same way, you know, either the same way, it's very difficult to try to stay on a positive note, if you know, the outcome may not be great. So you try to instill hope, but not give false truths. Trying to explain what's happening with a loved one, but not actually knowing enough about the disease to understand the total progression of what's going to happen, is tough to give an outlook. Well, what do you think's going to happen? I don't know. Because I haven't seen. Here's what I think's going on right now. And here's what we're doing because of it is more the theory for treatment there. We did eventually, as the, as the year went on, understand more about how it was going to trend but out of the gate, it was very difficult to have those conversations and then try to maintain honesty, throughout throughout that letting them know, I want to give you answers. I just may not have them right now.

BR 12:00

It sounds pretty difficult not knowing what is actually happening to a person but still trying to care for.

CD 12:08

Exactly.

BR 12:11

Moving on from your employment to more of your like, family and household life? How is COVID-19 affected you and your family's day to day lives?

CD 12:24

Well, my wife and I are both nurses. So we worked through the pandemic, however, we have three kids, and they weren't unable to go to school. So childcare and management that way was difficult. My wife was furloughed for a little bit, much like many other people. And, you know, we had to wear the budget differently that way. We couldn't see family, you know, and you know, I guess it brought, I would say it brought a closeness to our family network. But it was hard to be separate from the rest of the world for a while.

BR 13:09

Did you have concerns working in a COVID Ward? And bringing that home to your family?

CD 13:17

That's a great question. I will let you know what I tell a lot of folks. We're fortunate in healthcare, right? So yes, I'm exposed closer to the known disease than then you are. But to give an analogy, you would go into Walmart or a gas station, wearing your mask and you try to stay away from people and then you go home. You don't know how many folks here around that have COVID or may not have COVID or any other disease for that matter. And then you go home, I know that I'm around them. But I'm also have the benefit of having the proper precautions. And the right supplies to do my job. I had a papper, I had gowns, I had gloves. I had negative pressure ventilation, I had everything set up for myself to stay safe. And then I was able to change my clothes and and we had processes set up so that when I left here, I was at the least amount of risk. So I felt I felt confident going home. Knowing that I used all those proper precautions, then I trust the system as I always have. And those things worked. Yeah, I trusted that. However, that being said, the caveat to that is what if PPE becomes a shortage. I did not have to experience that. We did monitoring of our supplies to make sure that we didn't run short. We tried to find ways in which to conserve, but much like the news set around the country. I in our local setting, I did not experience a shortage of PBE we always had enough to get by and stay safe

BR 15:02

That's great. How are you managing the day to day activities of your household?

CD 15:13

Currently, right now, my kids go four days a week to school, they're back to four days a week, and they still wear masks everywhere they go. But as far as, as far as segregation goes, we've definitely loosened the reins around what I would call our, our house in our neighborhood, you know, many people are vaccinated now where it's not as concerning, and we follow the CDC recommendations as best we can to, to make sure that we're doing the best for everybody around us. So right now are my are my kids that everybody else tired of the masks? Sure. But I really do believe that we've seen the effects of what good good hygiene and, and masking can do. And that's evidenced by the, you know, the reduced flu season and things like that, that, you know, if we stay a little bit cleaner, and we wash a little bit more, you know, we can do some good things. So and then the vaccines obviously, coming out, is very, very helpful for that herd immunity.

BR 16:15

It really, really is. How does the COVID-19 outbreak affect your communities be like your church club that your kids are in? Anything like that.

CD 16:31

Yes. So you know, that's a great example, when you think of church we have never had, we've never had a closed down church before, we have a very large community in our church. And with, you know, 1000s of people kind of coming through the door every day, to not actually be able to go there, they've done more outside services. And we actually, they've actually got very heavily into the multimedia online version of that, which, you know, is a great thing and tell you the truth, we find it more convenient for those times in which we do have other obligations that we can't avoid, to be able to attend. So what I say that we attend more often because it's virtual Sure. I think that we realized with school, my daughter's school, they had a snow day, but they didn't call it a snow day they'd had it or work from home day, because they were so used to doing online virtual schooling, that it wasn't a day that you're not in school, it's a day that you're just going to work from home and they know they can pull that off now. So many things have gone virtual, much like telehealth, in medicine that are they're leaning on heavily noticing that actually, it's it's very effective, and, and also cost effective for a lot of folks. So there's been some very good changes that we identified from the COVID pandemic. It's not it's not all, you know, sadness and, and things like that, but, but we learned a lot of things that are, you know, going to continue on going forward.

BR 18:02

How have your children adapted to the part in time or part in school and part online?

CD 18:11

You know, we are we're a fortunate family, my kids, sort of like that multimedia, I think it's very helpful that multimedia is such a big part of the youth life these days, so that they're used to looking at a screen talking to their friends on FaceTime and things like that. So, so honestly, they, they missed their friends, but they didn't miss getting up for the bus. So, you know, there's there's the good and the bad. But but they did they did fine. I think, I think that they would have maybe advanced just a hair more in their classes, they've they've all done very well, at least in our family. But do I think that they're a little bit more teacher, one on one contact, that that classroom focus that you get, versus maybe a few home distractions here and there. They probably would have done better in the school setting, and I'm sure they will going forward. But but they managed, they all knew what they were doing. And they're anywhere they're 12, 10 or 12, 10, and 7. So they, they were able to focus enough to get all their work done every day.

BR 19:14

How are people around you responding to the covid 19 pandemic?

CD 19:22

I feel that you really have to look at each person and each family as individuals. I can say there's any word from people still, you know, not wanting to be around other people and we respect that that they want to segregate and still work on 9 to 5's and, and and lockdown and there's there's other folks that you know, take the the non mandated or this the state reduction, a mandate of masking the other way and and they felt this they don't have to they don't want to and I think really you just have to not judge it. Just let other people do what what they think is right and, and just maintain your own? So how do I think other people responding? I think they respond as individuals going off their own ethics values and what they believe. And you know what, I'm doing the same, but I just don't judge anybody for what, what they think they should do.

BR 20:17

Have you seen any people around you change their opinions over the course of the pandemic?

CD 20:25

Yes, I think that I think that the emotions, the highs and lows of emotions, especially when it comes to, you know, a lot of this wasn't just Health and Health and Human safety. But a lot of it was financial, financially driven opinions. And what I did notice with a lot of folks was, you know, the furloughs was tough. When people weren't able to go to work, that was very difficult. And some people However, some other walks of life, with the, with the unemployment going up in the in the guaranteed additional, you know, they had those $600 stipends, and things like that they came out, some people were, were actually furloughed making more money on furlough than they were at their job, depending on your type of job. So, you know, there was there was a lot of financial emotions out there of I can't make it day to day. And, and please don't bring me back to work, you know, I'm doing better right now. So, but also that creates animosity between people too, right? Because, you know, here it was. And I'm sure any other employer would say the same you furlough somebody, and they're really bummed about it, and you feel really bad about it. And then they came up with the unemployment. So now they're doing okay, but now we're starting to loosen the restrictions. So now you need them to come back to work. And that also causes animosity, because now you're calling somebody back, and it becomes why me, not them. You know, I need my job. And then the, you know, and then the unemployment bonus went away. And then it's, well, now I want to come back to work. So you just have to understand that people's, you know, people's checkbook, was a big driver in what they wanted to hear from the way the COVID pandemic was going. And, you know, it's not as bad as it was, we should all be at work, or always terrible, you know, they need to support us financially this way, the government needs to do this. But it's all your personal situation, I think that really makes your emotions sway in such a way.

BR 22:27

Has COVID-19 changed your relationships with family and friends and the community?

CD 22:35

No, I don't think so. I think if anything change would have been for the positive knowing that you really saw I really saw here and I'm very fortunate for that 99% of the people were trying to do the right thing. And they were trying to figure out any way to help you know, I put out a thing when COVID first started. We put out a request for masks, right. And when there was a nationwide peepee shortage, and the amount of boxes 1000s and 1000s of masks and things that we got from folks, people coming, coming up with ideas to make specialized gowns or eye shields and things like that it was just really amazing to watch everybody in the community come together with with options to make us be safe and successful. I really was very impressed with I always say in times of crisis, people pulled together and they throw they set aside all their personal biases.

BR 23:39

Was that a one time community drive to get PP? Or did you guys do that multiple times?

CD 23:46

It went on for quite a while until until honestly, most of the general public right away it was a big deal because we had enough for our staff but we didn't have enough for patients but we needed patients to come in if they were going to need to come into the building we needed them to have masks, we didn't have enough for the staff and for the patients to give each patient who comes in for you know, say an hour to a mask and then they leave and we have to discard it. So the donations really came from when like you for example you would come to the clinic I'm sorry, I don't have a mask we use we gave you one of the donated masks to you and that way when you left you would have one as time went on with COVID and face coverings became mandatory everywhere you know as long as I do everywhere you go now everybody's got a mask so we just we just didn't need it anymore. But we needed it right away we didn't have any way to keep everyone safe and ourselves as well. So yes, as the need went down we stopped quote needing those donations. Because you can pick up a box now at Walmart if you need

BR 24:45

Yeah.

CD 24:48

Hi Matt I'm on with Bennett.

Matt Schneider 24:51

You are? Okay. I just he's given me a lecture about how interviews are only conducted one on one and I'm not invited. So I guess I just want to get up in your ear to be just very careful and cautious.

CD 25:02

He's on speaker with you and me.

MS 25:05

Okay. Bennett.

BR 25:07

Hi.

MS 25:09

Bennett. Are you familiar with HIPAA?

BR 25:12

Not particularly.

MS 25:15

Yeah, okay, we healthcare systems are required to abide by patient privacy, federal laws and laws are violated. Both you and our institution and Chris, as an individual could face some civil and criminal penalties basically. So that my reason for just wanting to be able to sit in is just to make sure those, you know, no lines across Chris is an experienced pro and I trust him. But sometimes you want to get rolling on telling a story. So that that's the reason why I want to be a part of this is I'm sure you're not aware of that. I was certain you weren't aware of those rules. So that's why.

BR 25:57

Sorry I had no idea. Sorry.

CD 25:59

No, it's all good. We haven't shared anything. Anything specific only generalized ideas.

MS 26:05

Perfect. Perfect. I trust you. But Mr. Mr. Running here...

CD 26:15

No, you're good. Go ahead, Bennett. I'll just leave you on speaker there, Matt.

BR 26:20

I can certainly send you the full transcript of the full interview. Before I submit it, of the 20 minutes that we did previously. Just so there's no..

CD 26:37

Yeah, it would be really nice. That'd be great. But yeah, so far, so good. So keep on rolling.

BR 26:46

Have anybody you know, got sick during the COVID-19 outbreak, and what was your experience in responding to their cities?

CD 26:54

You know, I have, I have known a lot of individuals for, you know, personally, and, you know, by by proxy. And, you know, the acuity definitely varied. Some, some of my, you know, family and friends got very, you know, got very ill, we have had some, some known folks, which in our familial community, pass away, and we've had others who tested positive and didn't even know they had it. So that's, that's what's really interesting about about this, you know, viral progression is, you just are not sure how it's going to hit each individual, I'll say I found this disease interesting. Because you could have one person in the family are two people in a family be positive, and the other three, they live together and eat together every day, be negative. So it's just such a unique scenario on why I'm interested to see study 10 years down the road of, of, you know, was there other? Was there other factors in which I have that maybe my wife didn't have, you know, and unfortunately, neither one of us have had COVID. But, you know, what, what are those things going to be that say, Oh, well, we now know that if you had this factor, you were more susceptible to that. So it's just interesting.

BR 28:17

Has your mental health been affected by the pandemic?

CD 28:26

I think there was times you know, in the, in the heat of the COVID pandemic, you know, where, where the communication and the amount of change and the adaptability that we needed to portray every day. It just got wearing, because, right, when you felt like you got settled, and you had good communication, and we were really doing all the right things, things would change a little bit. And you'd kind of go back to the drawing board, and that was okay, but you're kind of one foot in the pond, and one foot out of the pond in that was the thing is you just kept trying to do the next right thing. So yeah, mentally it was wearing I didn't ever get, I wouldn't say I would never got depressed. But frustrated from time to time. Sure. Only because our hearts in the right place, though. You want to do the best care and you're trying to do the best care. And then you kind of get a little curveball again. And so you go with that. And, you know, you do that over and over. And at some point, you're just thinking, my goodness, we could all use a little break. And you know, right now I got to tell you, we were we're doing we're doing pretty good. So we're feeling like we can breathe free air a little bit more now. So that's great.

BR 29:39

Would you say that's the general experience of those healthcare providers in general? Or do you think overall, there was a different experience?

CD 29:49

I think it depends on your setting. And the way that you deal with these experiences and some of this loss You know, everybody kind of takes it takes it a little bit differently, that's such a, that's going to be such an individualized reaction to the COVID pandemic, as you've heard before, glass half full glass half empty, you know, one person might say, you know, I lost a patient today, and the next person might say, I saved for. So it's always going to be your your outlook on it, that you, you did the best you could with this, the skills and the abilities that you had at the time. And and then you just have to accept the outcomes after that. So I would say that we everybody, I can't speak for the whole country, everybody did the best they could somebody saw 1000 deaths, and somebody may not have ever seen a death, obviously, they would each react completely different than the other one. It's just going to be so independent. On your experience. I will say that my experience, although it was it was happy and sad, and frustrating and interesting, all at the same time. That you just won't forget it, you know, but I can't say that. I can't say that the whole thing was a total loss at all, I think that we did a very good job for our community with what we could work with.

BR 31:18

Were you was your clinic involved? Like did it converting to giving out vaccines? Or is it still a COVID word?

CD 31:29

We are we are able to treat patients with COVID here. But we also are able to serve the community and our patients with with vaccines, we do get our allotment much like many other facilities. Yep. So we get vaccines every day.

BR 31:46

Have you received any pushback for providing vaccines?

CD 31:52

Not that I've heard. I think that's been a pretty positive thing that we're offering the community, I haven't heard any negative feedback for giving vaccine.

MS 32:00