Item

Silenced voices of the commoner

Title (Dublin Core)

Silenced voices of the commoner

Disclaimer (Dublin Core)

DISCLAIMER: This item may be missing media that was intended to be included.

Description (Dublin Core)

The recent Covid-19 pandemic has had immense local and global ramifications, especially for us Victorians who have experienced the world’s longest lockdowns. It was a significant worldwide event which will certainly be looked back upon by future generations, just as we have analysed previous historical diseases, such as the bubonic plague. But how should archivists determine which sources, and likewise which voices should be permanently preserved within the historical record?

Traditionally, an archive is a collection of documents that archivists have selected to be permanently preserved as sources for future historical or other forms of research. Initially, only scholars with an ambition to conduct historical research had access to archives, but their digitisation and free nature have ensured that anyone is able to access the documents they contain online.

However, the process of creating both physical and digital archives is inherently flawed. Archivists have a formidable power to evaluate which sources are “worthy of inclusion”, and simultaneously which ones are not; essentially what compromises the historical record.

Therefore, although archivists are characterised as unbiased and impartial individuals, they are inextricably influenced by “societal biases” in their decision-making, as they simply have to select what they personally believe will have value to future researchers. It has culminated in them privileging and prioritising the voices of individuals within positions power, which has indefinitely created “gaps within the historical record” through inhibiting the voices of those without it.

Rodney G.S. Carter echoes the problem in asserting that the existence of archival “silences” is the “manifestation of the actions of the powerful”, which has a substantial impact on how marginalised groups produce and likewise form both social history and memory. Ariella Aïsha Azoulay has cautioned readers that “digital archives are no exception”.

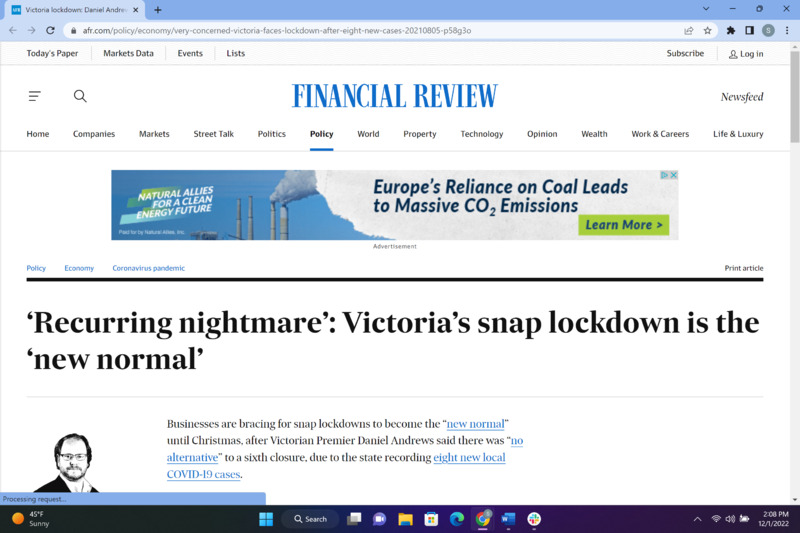

With this in mind, if we consider the 19-month impact of the pandemic upon Victoria, I am certain that archivists will acknowledge the voices of those within positions of power when determining what sources should be preserved. Of particular importance would be those of primary actors that shaped Victoria’s lockdown experience, most importantly the protagonist of the lockdowns, Premier Daniel Andrews (fig.1).

Figure 1. Video of Premier announcing sixth lockdown, cited in Patrick Durkin, “’Recuring nightmare’: Victoria’s snap lockdown is the ‘new normal,’” Financial Review, August 5, 2021, URL: https://www.afr.com/policy/economy/very-concerned-victoria-faces-lockdown-after-eight-new-cases-20210805-p58g3o.

I am aware of the threat of “information overload” both real and digital archives currently face with an abundance of available sources, but I would argue that the preservation of major political statements alongside previously supressed voices would be beneficial to any archive created surrounding the Victorian Covid-19 experience.

A consideration of the experiences of marginalised voices would be imperative to a future historian, as it would enrich historiography by offering insight into the social-political dynamics of the event, and its psychological impact beyond official government and political documents.

I will now consider the value of this “bottom-up approach” in capturing the Victorian pandemic experience from the viewpoint of the common man, me, a historically marginalised group within the realm of archives.

I personally wasn’t too concerned about the first lockdown and its stage three and four restrictions as they would “flatten the curve” of infectious cases, providing our health system with the best opportunity to tackle the fast-spreading virus. Life as we know it changed though with only four reasons to leave home; shopping, exercise, caregiving, and work. The café I worked at had to shift to “take away only”, as many others (fig.2).

Figure 2. The Food Republic Café, “covid update for customers,” Blackburn, March 23, 2020, URL: https://www.facebook.com/thefoodrepubliccafe.

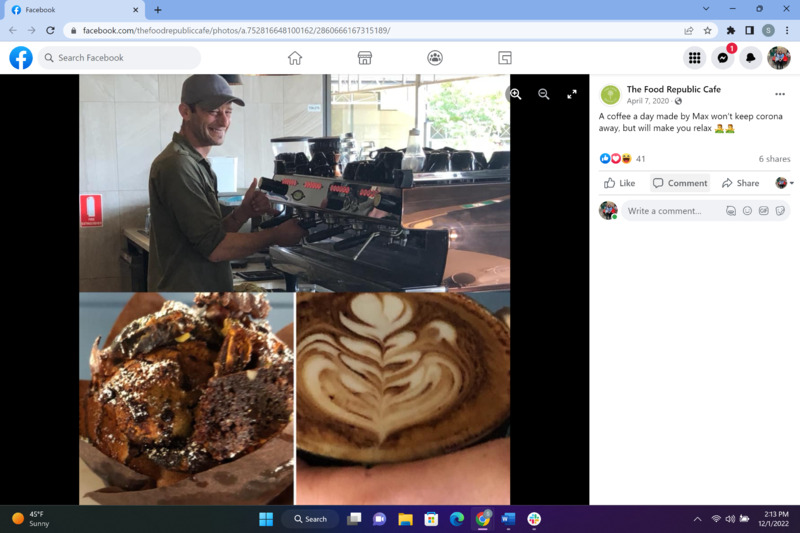

I was still able to work alongside my barista colleague and friend Max which was pretty good, and I was able to perfect my coffee artwork (fig.3).

Figure 3. The Food Republic Café, “promotional post during lockdown 1” Blackburn, April 8, 2020, URL: https://www.facebook.com/thefoodrepubliccafe.

I was also able to continue exercising and riding my bike, but I wasn’t able to see or visit any friends or family, which initially seemed like a fair sacrifice to make for the health and wellbeing of all Victorians (fig.4).

Figure 4. George Vesnaver, Selfie on bike ride, April 10, 2020, photograph, Main Yarra Trail, Melbourne.

However, after being continuously plunged in and out of lockdowns by the time the sixth one came about, I was very angry to say the least as representative within my covid journal entry (fig. 5).

Figure 5. George Vesnaver, Covid Journal Entry, October 27, 2022, photograph, Kew East, Melbourne.

Laura A. Millar’s observation that “the concept of evidence” must be broadened as opposed to its current restrictive and rigid format adopted by archivists has reaffirmed my belief that my experience and that of other regular people should not be forgotten.

My sources may just seem like information to an archivist because of their form, but they are filled with evidence of this historic moment. Their eternal preservation within an archive would serve anyone wanting to write about the Victorian Covid-19 experience in the foreseeable future. For example, figure 2. would enable one to see how government information was disseminated via social media; the confirming and likewise conforming of political decisions. Figure 3. would reveal the way in which people adapted to Victoria’s first initial lockdown via humour, helping us remember attitudes towards the past event. Figure 4. would showcase a sense of normality during unprecedented times, through an ability to continue exercising. But most importantly the response depicted in figure 5. towards figure 1., a first-hand account of the psychological impact of the endless lockdowns instigated by those with political powers.

Winston Churchill once said that “history is written by the victors”, so considering those with and without power survived the pandemic it seems only fair that all our voices should be recognised in the historical record.

Traditionally, an archive is a collection of documents that archivists have selected to be permanently preserved as sources for future historical or other forms of research. Initially, only scholars with an ambition to conduct historical research had access to archives, but their digitisation and free nature have ensured that anyone is able to access the documents they contain online.

However, the process of creating both physical and digital archives is inherently flawed. Archivists have a formidable power to evaluate which sources are “worthy of inclusion”, and simultaneously which ones are not; essentially what compromises the historical record.

Therefore, although archivists are characterised as unbiased and impartial individuals, they are inextricably influenced by “societal biases” in their decision-making, as they simply have to select what they personally believe will have value to future researchers. It has culminated in them privileging and prioritising the voices of individuals within positions power, which has indefinitely created “gaps within the historical record” through inhibiting the voices of those without it.

Rodney G.S. Carter echoes the problem in asserting that the existence of archival “silences” is the “manifestation of the actions of the powerful”, which has a substantial impact on how marginalised groups produce and likewise form both social history and memory. Ariella Aïsha Azoulay has cautioned readers that “digital archives are no exception”.

With this in mind, if we consider the 19-month impact of the pandemic upon Victoria, I am certain that archivists will acknowledge the voices of those within positions of power when determining what sources should be preserved. Of particular importance would be those of primary actors that shaped Victoria’s lockdown experience, most importantly the protagonist of the lockdowns, Premier Daniel Andrews (fig.1).

Figure 1. Video of Premier announcing sixth lockdown, cited in Patrick Durkin, “’Recuring nightmare’: Victoria’s snap lockdown is the ‘new normal,’” Financial Review, August 5, 2021, URL: https://www.afr.com/policy/economy/very-concerned-victoria-faces-lockdown-after-eight-new-cases-20210805-p58g3o.

I am aware of the threat of “information overload” both real and digital archives currently face with an abundance of available sources, but I would argue that the preservation of major political statements alongside previously supressed voices would be beneficial to any archive created surrounding the Victorian Covid-19 experience.

A consideration of the experiences of marginalised voices would be imperative to a future historian, as it would enrich historiography by offering insight into the social-political dynamics of the event, and its psychological impact beyond official government and political documents.

I will now consider the value of this “bottom-up approach” in capturing the Victorian pandemic experience from the viewpoint of the common man, me, a historically marginalised group within the realm of archives.

I personally wasn’t too concerned about the first lockdown and its stage three and four restrictions as they would “flatten the curve” of infectious cases, providing our health system with the best opportunity to tackle the fast-spreading virus. Life as we know it changed though with only four reasons to leave home; shopping, exercise, caregiving, and work. The café I worked at had to shift to “take away only”, as many others (fig.2).

Figure 2. The Food Republic Café, “covid update for customers,” Blackburn, March 23, 2020, URL: https://www.facebook.com/thefoodrepubliccafe.

I was still able to work alongside my barista colleague and friend Max which was pretty good, and I was able to perfect my coffee artwork (fig.3).

Figure 3. The Food Republic Café, “promotional post during lockdown 1” Blackburn, April 8, 2020, URL: https://www.facebook.com/thefoodrepubliccafe.

I was also able to continue exercising and riding my bike, but I wasn’t able to see or visit any friends or family, which initially seemed like a fair sacrifice to make for the health and wellbeing of all Victorians (fig.4).

Figure 4. George Vesnaver, Selfie on bike ride, April 10, 2020, photograph, Main Yarra Trail, Melbourne.

However, after being continuously plunged in and out of lockdowns by the time the sixth one came about, I was very angry to say the least as representative within my covid journal entry (fig. 5).

Figure 5. George Vesnaver, Covid Journal Entry, October 27, 2022, photograph, Kew East, Melbourne.

Laura A. Millar’s observation that “the concept of evidence” must be broadened as opposed to its current restrictive and rigid format adopted by archivists has reaffirmed my belief that my experience and that of other regular people should not be forgotten.

My sources may just seem like information to an archivist because of their form, but they are filled with evidence of this historic moment. Their eternal preservation within an archive would serve anyone wanting to write about the Victorian Covid-19 experience in the foreseeable future. For example, figure 2. would enable one to see how government information was disseminated via social media; the confirming and likewise conforming of political decisions. Figure 3. would reveal the way in which people adapted to Victoria’s first initial lockdown via humour, helping us remember attitudes towards the past event. Figure 4. would showcase a sense of normality during unprecedented times, through an ability to continue exercising. But most importantly the response depicted in figure 5. towards figure 1., a first-hand account of the psychological impact of the endless lockdowns instigated by those with political powers.

Winston Churchill once said that “history is written by the victors”, so considering those with and without power survived the pandemic it seems only fair that all our voices should be recognised in the historical record.

Date (Dublin Core)

Creator (Dublin Core)

Contributor (Dublin Core)

Type (Dublin Core)

Video

Facebook posts

selfie

picture of Journal entry

Link (Bibliographic Ontology)

Controlled Vocabulary (Dublin Core)

English

Food & Drink

English

Emotion

English

Politics

English

Social Media (including Memes)

English

News coverage

Curator's Tags (Omeka Classic)

Contributor's Tags (a true folksonomy) (Friend of a Friend)

Date Submitted (Dublin Core)

10/29/2022

Date Modified (Dublin Core)

12/01/2022

04/03/2023

Date Created (Dublin Core)

10/30/2022

Item sets

This item was submitted on October 29, 2022 by George Vesnaver using the form “Share Your Story” on the site “A Journal of the Plague Year”: https://covid-19archive.org/s/archive

Click here to view the collected data.