Items

Mediator is exactly

Law Enforcement

-

12/07/2021

12/07/2021Heather Perrault Oral History, 2021/12/07

Heather Perrault is an Eau Claire, WI resident and currently works for the Wisconsin Department of Corrections as a parole officer. In this interview, Heather talks about her experience with COVID and how it affected her life as a stay-at-home mom/ pseudo-teacher for her kids as well as her job that she rejoined about halfway through COVID. She also talks about how COVID has affected her family and friends in terms of their physical and mental health and how the people she oversees as a parole officer may be affected by COVID as well. Heather also gives future generations advice on how she thinks they should look at information about the pandemic in the future. -

2020-05-28

Covid 19- The First Wave

Schools were shut down, business were closing. My parents stood outside my living room waving as they dropped off Easter baskets for my children. The monotonous routine of my husband coming home from his shift as a police officer and bagging his uniform in a garbage bag in the garage so I could immediately wash them for fear he had brought home Covid. Two months passed of this until that dreadful day when neither of us could smell or taste anything. He had brought home Covid. At first, it felt just like a cold with the exception of the loss of taste and smell. But a few days into our positive results, my husband's symptoms became more severe. He began having trouble breathing at night. We had medicines and took precautions to get him through those nights. I was scared because we had two young children at home and they began to show signs of Covid as well. I didn't feel like I had anywhere to turn. In the beginning, you were told only to come to an ER if it was absolutely necessary and even then, the people who were checking into the hospitals were not checking out. It felt like a death trap to bring in my husband. Days passed and symptoms improved. We were lucky, it had passed. We had long-lasting effects when it came to rapid heart rates and regaining our taste and smell, but feel very lucky we eventually recovered. -

August 30th, 2020

August 30th, 2020Mayor DeBlasio visits Staten Island

Former Mayor Bill DeBlasio visiting Staten Island Branch of the New York City Police Department -

August 24, 2020

August 24, 2020Co-Vid car stops in Staten Island

Co-Vid car stops in Staten Island Sheriff advised me that they have a combination of 10 cars, a mix of TLC and Sheriff cars.They are staging by the entrance of the Outerbridge crossing administration bldg near page Ave. Steve white 8/6/20 -

2020-03-24

2020-03-24Mental Breakdown

My sister, Heidi, passed away in Washington, DC, on March 23, 2020. I wasn’t allowed to be with her when she died. My sister was my best friend. I was so lost. Her children, Significant other, my mother, her best friend, and I couldn’t have a funeral for her because of the rules put into place for Covid. So, we could not have a memorial for her till and year and four months later. At the same time, everything began to shut down. My husband works for the NYPD; I was terrified of him getting sick and losing him. Every day after he left for work, I would fall on the floor and break down in tears. I live next to a nursing home facility on Beach 119th St. in Rockaway Park. At this time, I would stare out my windows to look at the ocean to try to calm myself. For weeks, I would see out the right side of my windows and the ambulances and medical examiner vans showing up non-stop to the nursing home for ten days. Bodies were being taken out morning, noon, and night. The flashing red lights signaled that my mental health was in danger. I felt myself crashing many times. I was devasted. To this day, I carry so much internal trauma, I don’t know if I’ll ever recover. I hate this world and the cruel people in it. People have become so ugly because of Covid. I doubt I’ll ever be able to escape the mental anguish that lives in my soul... -

2022-05-26

2022-05-26From COVID-19 to shootings: Is mass death now tolerated in America?

This is a news story from The Associated Press. Just recently, there have been over one million COVID deaths recorded in the United States. The author of this piece asks if Americans have just begun to tolerate mass death. Racial and social inequalities are also cited, where the author claims that those of certain backgrounds are more likely to die sooner or more violently. The COVID deaths are then related to the recent shooting deaths, such as in Buffalo and in Texas. While the gun violence deaths are lower than the COVID deaths, the author uses this to show that little is being done for either to help lessen the amount of deaths. I don't agree with the author completely on this due to dying from COVID being very different from dying from a mass shooter. With COVID, people could pass it along unknowingly and get someone infected, as it is an asymptomatic spread. With a mass shooter, it is much less predictable and far more sudden. From what I have seen on my social media, I did not see anyone I follow really mark the 1,000,000 COVID death milestone, but many have expressed outrage over both the Buffalo and Texas shootings. I don't think the question should be whether Americans accept mass death or not, but of methods of prevention. Obviously, gun ownership won't solve all problems. The police that had guns were waiting outside the school as the shooter was slaughtering kids and adults. Though, one man with a gun, a border patrol agent, is who finally shot the mass shooter and killed him. This is more of a question of character, as well as how competent police forces are in these scenarios. I do not think the author made a fair comparison because protecting yourself from COVID to prevent death would be an entirely different process than protecting yourself from a mass shooter. While the goal of preserving life is the same, the methods differ. Outrage isn't an issue because I have seen people upset over death from COVID and mass shootings. The main problem I see is that people have trouble coming together on a solution. -

2022-05-13

2022-05-13INDY PRIDE FESTIVAL ORGANIZERS HOPE TO RECLAIM CROWDS AFTER COVID

This is a news story from WIBC by Chris Davis. According to the article, the Indy Pride Festival will be back after a two year hiatus due to COVID. The event will be held Indianapolis. Since the hiatus, some changes have been made. Cops at Pride will be in softer uniforms to make them more approachable. This will include shorts instead of the standard pants. There will also be police on bicycle patrol during the event. Shelly Snider, an executive director of the parade, says that the goal is to help queer people feel safe from major incident, but understands the rough relationship queer people in the past have had with the police force in general. -

2022-04-13

2022-04-13700 Chicago officers are refusing the city’s vaccine mandate without consequence

This is a news story from WBEZ Chicago by Patrick Smith. This story is about 700 police officers in Chicago refusing to comply with the vaccine mandates. Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot promised that officers refusing to abide by the mandate will face consequences by being placed on a no-pay status. Figures from the Chicago Police Department show that almost no officers have faced consequences for refusing vaccination. In total, the number of unvaccinated cops in Chicago is 2,110. -

05/03/2021

05/03/2021Kyle Sauley Oral History, 2021/05/03

-

05/09/2021

05/09/2021Josh Miller Oral History, 2021/05/07

Josh Miller is from Eau Claire, Wisconsin and he is a police officer. We discuss how Covid 19 has impacted his work, family, and community and how he feels about the pandemic. -

04/30/2021

04/30/2021Daniel Monson Oral History, 2021/04/30

The contributor of this item did not include verbal or written consent. We attempted to contact contributor (or interviewee if possible) to get consent, but got no response or had incomplete contact information. We can not allow this interview to be listened to without consent but felt the metadata is important. The recording and transcript are retained by the archive and not public. Should you wish to listen to audio file reach out to the archive and we will attempt to get consent. -

2021-10-14

2021-10-14Smell of Covid in Carolina

This story of the pandemic deals with the sense of smell and how it relates to my experiences while working as a security guard at a local college. -

2021-01-11

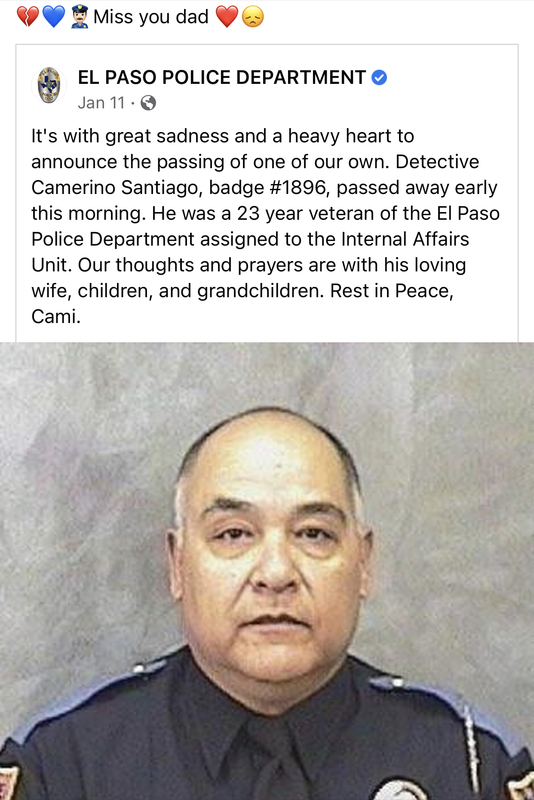

2021-01-11My Dad...The first EPPD officer to die from Covid-19

After a month of battling Covid-19, my father passed away due to complications caused by the virus. He was due to retire in January 2021. He worked for the El Paso Police Department for 23.5 years. His passing hit us all hard and it was unexpected as the doctors had told us several days before that he would make it. Then he took a turn for the worst. When his co-workers asked what did he look forward to in his retirement, he said spending time with his family and his granddaughter. We still miss him to this day, especially as the holidays approach. -

2021-10-04

2021-10-04Ashley Pierce Oral History, 2021/10/04

A quick comment about Law Enforcement during the pandemic. -

2021-10-04

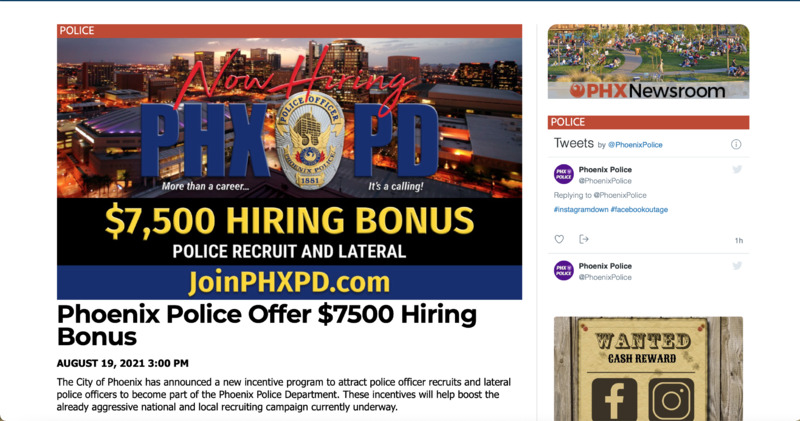

2021-10-04Show me the money

Working in law enforcement the past few years has been tough. So tough that many are reconsidering the career and either leaving or just not applying in the first place. So many agencies, including my own are now offering hiring incentives... and each agency is trying to offer better than the others to entice people to hire on. It has turned into an incentive frenzy... -

2021-09-17

2021-09-17Sobering Statistics

Once again, Covid-19 tops the list for Law Enforcement In Line of Duty Deaths, just as it did last year. Now, more than ever, Law Enforcement needs our support and assistance! -

2020-05

2020-05Remembering NYC 2020

These photographs taken from April-June 2020 capture New Yorkers interacting with the empty stress of the city during COVID-19. The first image displays an off duty fireman walking down vacant 5th Avenue, apparently in tribute. His body position highlights the stress, grief, determination, and exhaustion experienced by so many New York frontline workers. The next image was taken of the once bustling streets of SOHO. In this photograph, an older man appears exhilarated during a moment out of quarantine. Getting some fresh air, he turned up his car radio and bellowed out the lyrics of “New York, New York”, the anthem for New Yorkers. The third image captures young cyclists riding, practicing tricks, and laughing. The final snap is of two jazz musicians near the entrance to Central Park, a spot they often inhabited pre-pandemic. They played exactly as they once did, only masked this time. As a twenty year old who would normally be thrilled to spend the summer at home, surrounded by the lively energy of NYC, I was determined to find a way to interact with my city in a creative and safe way. After completing many projects from home (such as making filter masks for medical staff and collecting supplies for donation), I decided to use my knowledge of and passion for photography to capture fellow New Yorkers doing their part to help lower the spread of COVID and to find moments of camaraderie to fuel their, and others’, fight against this virus. In turn, the act of getting in my car and driving throughout the city, equipped with my Canon Rebel 55mm was my way of finding a measure of peace, purpose, joy, and meaning during the six long months in quarantine in New York City. -

2020-07-22

2020-07-22Chile wants Covid-19 sniffer dogs to help reopen public spaces

Police dogs in Chile are being trained to sniff out Covid-19 in humans, with hopes that they will facilitate the reopening of busy public spaces including malls, sports centers, bus terminals and airports this fall. The so-called "bio-detector" dogs are expected to complete training by mid-September and will be deployed to places with high concentrations of people, according to the Chilean police. -

2021-07-14

2021-07-14California woman first to face federal charges over fake COVID immunizations, vaccination cards

A homeopathic doctor in California became the first person in the United States to face federal charges over fake COVID-19 immunizations and falsified coronavirus vaccine cards. Juli A. Mazi, 41, of Napa was arrested Wednesday and charged with one count of wire fraud and one count of false statements related to health care matters, the Department of Justice said in a press release. "This defendant allegedly defrauded and endangered the public by preying on fears and spreading misinformation about FDA-authorized vaccinations, while also peddling fake treatments that put people’s lives at risk. Even worse, the defendant allegedly created counterfeit COVID-19 vaccination cards and instructed her customers to falsely mark that they had received a vaccine, allowing them to circumvent efforts to contain the spread of the disease," said Deputy Attorney General Lisa O. Monaco. -

2020-05

2020-05Masked Visitors

How has Covid-19 changed your daily life? My husband and I moved here in 2014 so I could volunteer with the city archaeologist, Carl Halbirt, and I have been doing that most every day since then. We have two new archaeologists now, but volunteers aren’t allowed until the virus social distancing is lifted. In November my husband died and after a short hiatus from volunteering I started again. Now, I am in my house with my dog every day. I miss being with people. Even our church is doing online services now. On Easter the priest printed large photos of many of our congregation and taped them to the pews, so it looks like we were in church. I saw myself, and right where I usually sit! How is your neighborhood and/or social circle responding to the crisis? My neighbors are all staying home like I am except for a few Flagler students who went to their parents homes. Some are furloughed, others are working from home. Since I’m retired, I’m just missing my volunteer work. Several of my friends and I have a group text several times a week so we can keep up with each other. My Community Hospice social worker is staying in touch with each of our grief support group members by phone, and several of us have exchanged phone numbers so we talk occasionally. The Tolomato Cemetery group is planning a Zoom visit on the third Saturday, which is the day we have the cemetery open for visitors. It will be my first Zoom conversation. I’m looking forward to that. My church, St. Cyprian’s is open each day for individual prayer and the commons and labyrinth are open as well for anyone who wants to pray or just sit in a peaceful place. How has Covid impacted your perspective of St. Augustine? I am happy that our city leaders have been proactive in closing so many businesses. I feel so sorry for the small business owners and workers who have lost their jobs, and I hope when the danger has passed we can get to a new normal. I don’t thing everything will be the same. I am hopeful the city will be able to help the businesses and workers with tax relief or some other means. I am proud of the way the police and firefighters are connecting with us by social media. How has Covid-19 impacted your use of social media? I’ve used it much more to keep up with friends near and far. I have also been using FaceTime with my daughter and son who live in other cities. I’ve been using Shipt to order my groceries for delivery to my house. What practices have you implemented to mitigate the impact of social distancing on your mental health? I’ve tried to make a small list of things I want to accomplish each day, but if I don’t finish it, I don’t beat myself up about it. It helps to keep me from sitting around watching mind numbing Hallmark movies. I’ve tried to walk most evenings around my neighborhood, just to be outside. I am reading books and doing jigsaw puzzles as well. I’ve cleaned/organized several cedar chests and drawers and I am working on bookshelves now. I am also writing a Corona Virus Journal describing my feelings (and there have so many emotional times during this quarantine) and making note of things I’m doing and friends I am talking with. It’s on my computer and I have no idea what I will do with it, but maybe my children will read it someday and maybe I will too. -

2021-04-26

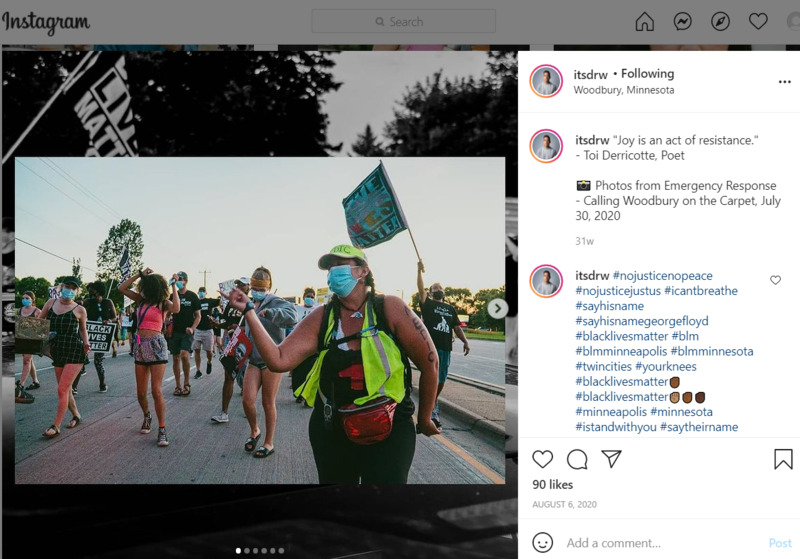

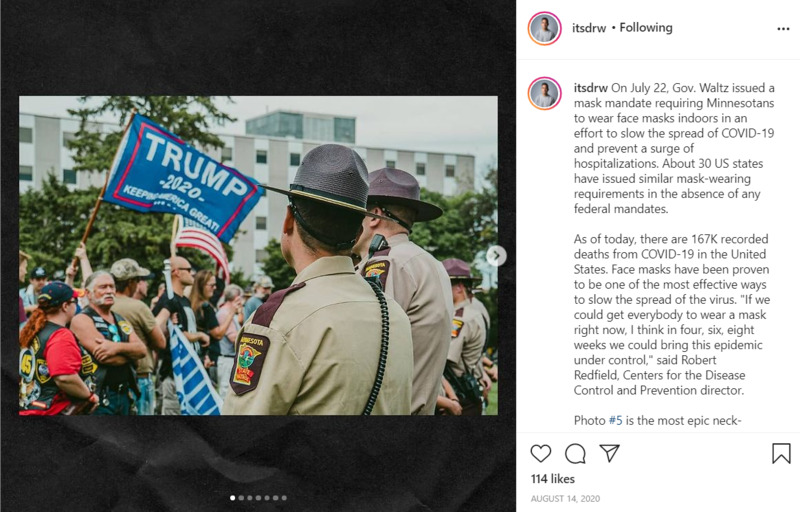

2021-04-26Image Submission for LE Collection Call

[1] This copyright-free image, courtesy of pexels.com, shows Corporal S. Brantley from the Wheeling (West Virginia) Police Department monitoring a protest. [2] This copyright-free image, courtesy of pexels.com, shows officers from the New York City Police Department, some of whom wear COVID face masks, beneath scaffolding on a sidewalk. -

2021-04-21

2021-04-21James Rayroux's JOTPY Portfolio

--Reflections on the Pandemic Archive-- Looking back over my experience with the “Journal of the Plague Year” COVID-19 archive, my prevailing emotion is gratitude. This opportunity granted me experience that few historians earn, and the remote, asynchronous work schedule allowed me to collaborate with my colleagues in ways that maximized our respective contributions. The breadth and depth of our individual experiences and perspectives tremendously improved our collective process and products. I spent enough time in the Arizona State Archives last year to recognize such collections as historical treasure chests, but I have now participated in processing an archive’s content and navigating the ethical dilemmas those submissions sometimes create. Archivists and curators are the history profession’s truly unsung heroes, and their work facilitates society’s perception of itself. My background in police work and public safety drew me to the archive’s existing Law Enforcement collection. In taking on that subset, I succeeded in reshaping the collection’s parameters to now include stories about police and law enforcement. I wanted to diversify the collection to encompass perspective of both the police and the public with whom they interact and serve. While some overlap exists between the Law Enforcement and Social Justice collections, each remains distinct. Through my contacts and writing, I promoted a Call for Submissions to an international audience of law enforcement professionals to reduce their relative silence within the archive. Within the archive’s content, I recognized that one’s location might shape their pandemic experience, and I created and designed an Arizona-based exhibit to explore that. Further research and discussion with my mentors and colleagues ensured the exhibit illustrated these differences without excluding visitors whose diverse experiences could further enrich the archived and exhibited content. I am proud of my “Arizona’s COVID-19 Pandemics” exhibit, particularly because of its compressed, one-month incubation period. Beyond displaying images, data, and stories representative of the diverse pandemic experiences within the state, the ACP exhibit offers visitors numerous levels of interaction and engagement to became active participants and create their own exhibit experience. Visitors can complete opinion surveys, add a story to the archive, explore additional content related to the displayed pieces, view ever-changing results from pre-defined archival content searches, conduct their own archival search, view collective visitor survey results, and apply to join the staff. The exhibit’s searches will include the archive’s future submissions, which reshapes both the exhibit and the experience visitors may have with it. A more detailed explanation of my ACP exhibit may be reviewed here: https://covid-19archive.org/s/archive/item/43037 Because of Dr. Kathleen Kole de Peralta and Dr. Mark Tebeau, I stand prepared to join research, curation, and exhibition teams and immediately contribute to their work products. Despite my gratitude for this experience and the opportunities it presented, I look forward to the day COVID-19 is no longer part of humanity’s daily vernacular. James Rayroux 22 April 2021 -

2021

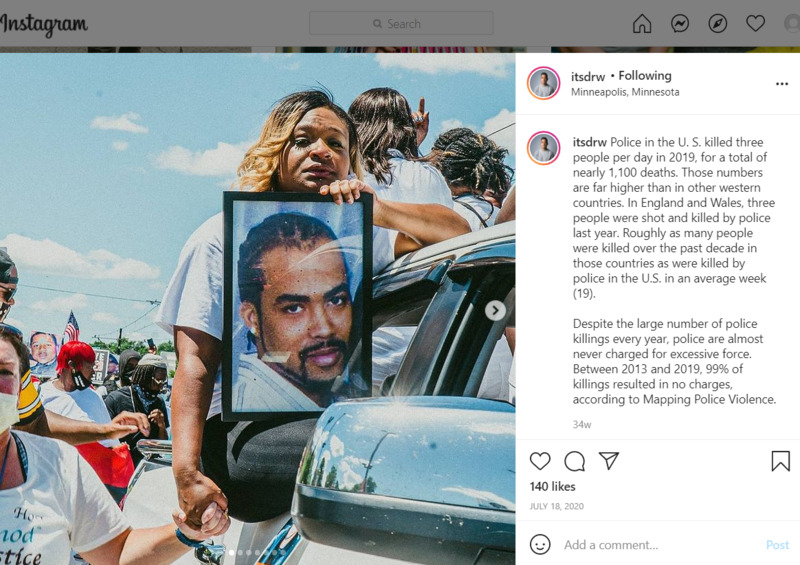

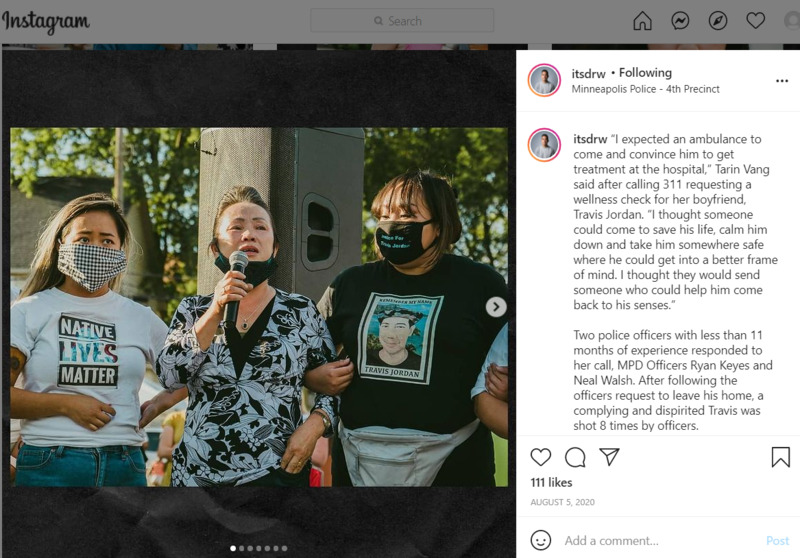

2021Policing Isn't Broken — It Was Designed This Way

Our policing institutions were designed to exert control over Black people. We need to limit the role, responsibilities, power, and funding of police so interactions that lead to the death of Black people don't happen in the first place. -

2021-04-20

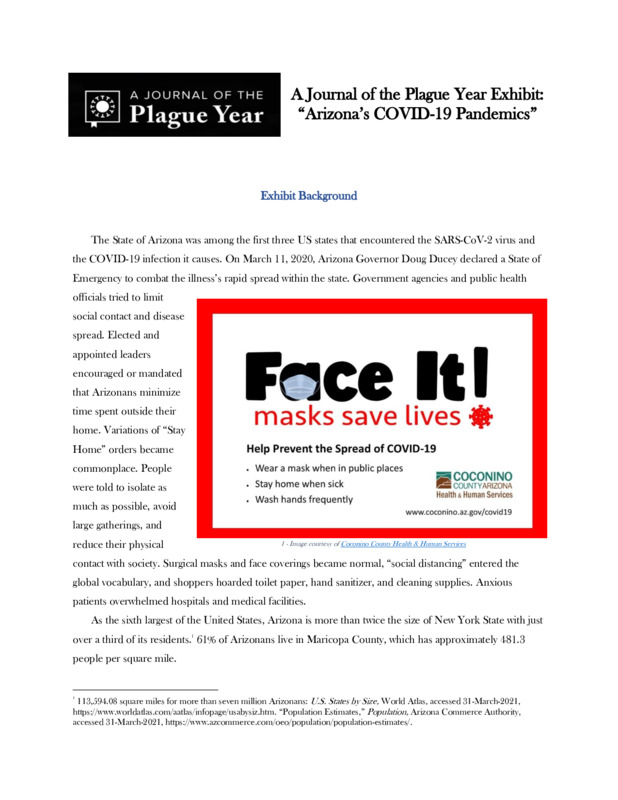

2021-04-20JOTPY Exhibit: "Arizona's COVID-19 Pandemics" by James Rayroux

While working as a curatorial intern on ASU's 'A Journal of the Plague Year' COVID-19 archive, I created this exhibit on the pandemic experience within the state. In addition to obvious, overarching realities such as socioeconomic status and immediate access to healthcare systems, I initially believed one of the greatest deciding factors that determined one's experience in Arizona was an individual's residence in either predominantly urban or rural environments. The proposed exhibit had been originally titled "A Tale of Two Arizonas" to pay respect to Charles Dickens and the differing realities experienced here. To test my proposed hypothesis, I went about finding data, stories, and submissions that substantiated or disputed my premise. Within a short time, I had identified four distinct environmental drivers of personal pandemic experiences; to me, that indicated the existence of many more I hadn't yet found or had overlooked along the way. My evidence suggested a minimum of four pandemic locales: Urban, Rural, Border, and Tribal within the State of Arizona and its fifteen counties. The recorded health data and personal experiences demonstrated the naivete of my initial hypothesis, and I retitled the exhibit: "Arizona's COVID-19 Pandemics." The Exhibit Background section illustrates the vast dichotomies within Arizona in terms of population density and access to healthcare facilities. Given the virus's respiratory nature, these factors seemed especially relevant to driving diverse local experiences. I chose to include a flyer from the Coconino County Health and Human Services' "Face It! Masks Save Lives" campaign. The flyer included a specific line to "Stay Home When Sick" that seemed to illustrate a different public health paradigm than the broader "stay home" orders from Maricopa and Pima county. This section also features an image of Sedona's red rocks and a portion of The Wave to remind visitors of the wide-open rural areas accessible to all, as well as those with cultural significance to the Native American tribes and limited access to the general public. The next section asks a short, five-question survey in which visitors may participate. The Silver Linings piece features a short audio clip of a father and husband discussing some unexpected benefits of the pandemic. Visitors may explore additional Silver Linings stories and submit their own experience. The Tséhootsooí Medical Center piece seeks to illustrate the different pandemic experience on the state's tribal lands. I hoped to inspire some relevant emotional turmoil for the visitors through the piece's visual presentation. I wanted to create a series of waves with quotes from the medical center's healthcare workers. I hoped visitors' attention would be drawn to the large, bolded key words, and that they would first experience the segments out of sequence because of that. After potentially feeling a sense of chaos, they might settle themselves into a deliberate reading of the texts and find their own order within the experiences provided here. This piece allows further exploration of Native submissions and topics, a review of an additional related news article, and a submission prompt that invites visitors to offer guidance to hospital managers. The next piece illustrates the differences between mask mandates in communities across Arizona. In addition to hearing an audio clip of interviews with mayors and a public health official, visitors can explore additional submissions related to mask mandates and submit their thoughts on statewide mandates. The Arizona Department of Health Services provides zip-code specific infection data on its website, and the wide array of known case infections therein further illustrates potential dichotomies across the state. In working to include and represent this data in a consumable way, I encountered inconsistencies with tribal data. The nation's Indian tribes are overseen by Indian Health Services, a federal public health agency, and it does not collect or report data in the same manner as the State of Arizona or its counties. At first glance, the data would seem to suggest that tribal areas had less severe pandemic experiences than the rural and urban areas, which was not objectively true. I wanted to offer the unedited data to visitors, allow them to drawn their own conclusions, and invite them to offer their thoughts on what potential misunderstandings might emanate from these reporting differences. Visitors may also choose to review the foundational data from this piece, as well. I used the following two sections to offer submission prompts about the visitor's overall pandemic experience as a function of their location, as well as what they might have done if placed in charge of their city, county, or state during this pandemic. A diverse Search section allows visitors to explore additional topics of interest to them. 23 hyperlinks offer pre-defined search parameters. An Advanced Search link allows self-defined research, and a Join The Staff link connects visitors with opportunities to work within the JOTPY archive. A final section asks visitors to provide feedback on the exhibit, its content, and the pandemic in general. Both surveys within the exhibit will display overall results to visitors who participate in them. Through this process, I found incredible amounts and diversity of data outside the archive that spoke to these generally localized experiences, but not that much yet within the archive explained what Arizonans had experienced outside the state's urban environments. I created a call for submissions and delivered it to fifty rural entities that might help support the effort to collect and preserve more rural Arizona stories. Between all the local libraries, historical societies, museums, small-town mayors, and county health officials to whom I asked for help, I am optimistic the archive will better represent all Arizonans in the coming months and years. Despite the exhibit having been created, I ensured its internal search features would include future submissions and allow the exhibit to remain relevant long after its release. -

2021-04-20

2021-04-20Images and Audio from "Arizona's COVID-19 Pandemics" Exhibit

During March and April 2021, I created an online exhibit from content within Arizona State University's "A Journal of the Plague Year" COVID-19 archive. Entitled "Arizona's COVID-19 Pandemics," the digital exhibit contained images previously submitted to the archive, along with several copyright-free images I found on pexels.com. I have attached all these images. Listed by their order of appearance within the exhibit, their sources are as follows: 1- "Face It" Campaign flyer: Coconino County Health & Human Services ( https://covid-19archive.org/s/archive/item/42998 ) 2- Red Rocks, Sedona: Courtesy of Gregory Whitcoe via Pexels.com 3- Online Learning: Courtesy of August de Richelieu via Pexels.com 4- Tséhootsooí Medical Center staff: Courtesy of FDIHB Marketing Department and Navajo Times newspaper ( https://covid-19archive.org/s/archive/item/41189 ) 5- Arizona's Mask Mandate Map: created by Sarandon Raboin ( https://covid-19archive.org/s/archive/item/26267 ) 6- Arizona COVID-19 Infection Zip Code Map: Courtesy of Arizona Department of Health Services ( https://covid-19archive.org/s/archive/item/42035 ) 7- Woman Shopping: Courtesy of Anna Shvets via Pexels.com 8- Woman on Rural Arizona Road: Courtesy of Taryn Elliot via Pexels.com 9- Masked Woman in Crowd: Courtesy of Redrecords via Pexels.com 10- The Wave: Courtesy of Flickr via Pexels.com (this image is found only in the PDF submission of the exhibit, not in the public-facing exhibit itself due to document formatting technicalities - the PDF version can be found at https://covid-19archive.org/s/archive/item/42998 ) -

2021-04-15

2021-04-15Daunte Wright's mom says she 'wants 100% accountability' in wake of officer's arrest

The mother of Daunte Wright, the 20-year-old Black man shot dead by a Minnesota police officer at a traffic stop, said she "wants 100% accountability" in the wake of the officer's arrest. "If that even happens, we're still going to bury our son," Wright's mother, Katie Wright, said at a Thursday news conference. "We're still never going to be able to see our baby boy." -

2021-04-17

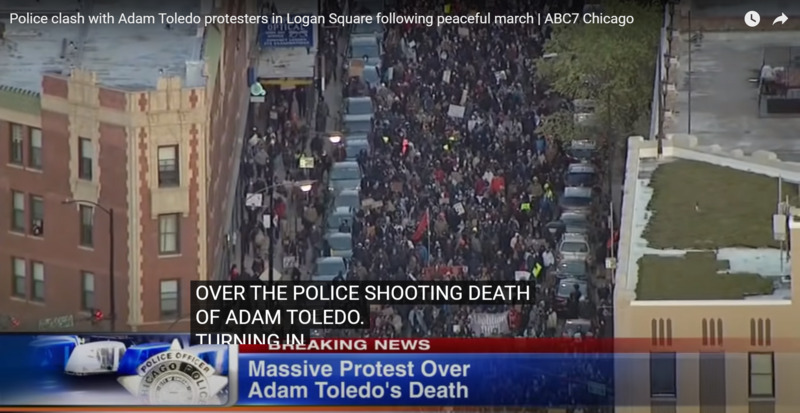

2021-04-17Police clash With protesters during Adam Toledo demonstrations

Police in Chicago, Illinois, clash with protesters during demonstrations for 13-year-old Adam Toledo following the release of the police body camera footage. -

2021-04-17

2021-04-17Police clash with Adam Toledo protesters in Logan Square following peaceful march

The march was largely peaceful, but as it came to an end around 10 p.m., a small group of protesters still lingering in the streets began scuffling with police. -

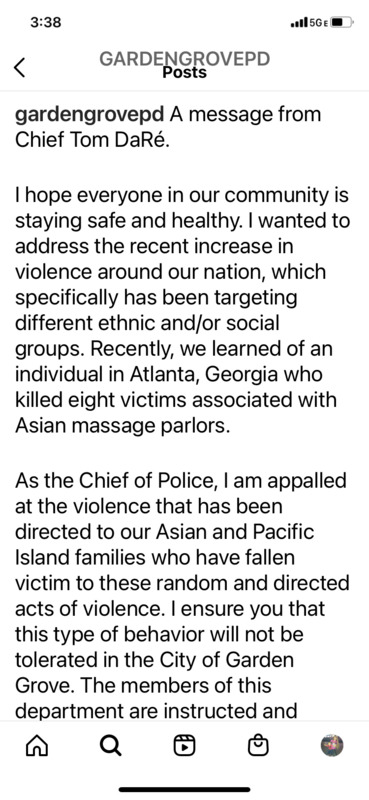

2021-03-26

2021-03-26Black Lawmaker Arrested For Knocking On Governor’s Office Door

State troopers arrested a Georgia lawmaker who was knocking on Gov. Brian Kemp’s office door, in protest of the closed-door signing of a bill that would restrict voter access. Critics, including Rep. Park Cannon, say the new laws will disenfranchise Black and Democratic voters. “I am not the first Georgian to be arrested for fighting voter suppression. I’d love to say I’m the last, but we know that isn’t true.” -

2021-04-09

2021-04-09That time we closed down Figueroa street in protest fighting injustices to the people!

#TBT That time we closed down Figueroa street in protest fighting injustices to the people! - If you saw my recent IG story where the police violated the rights of a black Deaf woman, this is a reminder we need to keep standing up, speaking up for our rights to be treated as a human being. I can not tolerate a world where those with power prey on those who understand thier power. - When I say Black Lives Matter this what I stand for everything else you see is just noise and will push away because all I know is Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. - Stand with Me. Let's do our part to shape a better world. Power to the People all the time.✊🏿 - 📷 Gratitude @aanaconda -

2021-03-10

2021-03-10Op/Ed: How to get officers back up to speed in a post-COVID world

In this article, retired California Highway Patrol Lieutenant, attorney, and professional risk manager Gordon Graham discusses the factors police agencies should be considering and planning for as we hope to soon begin transitioning to a post-COVID/post-pandemic world. Among these are traditional and analogous considerations agencies have long dealt with, such as the return of employees from extended military assignments or recovery from injuries. Many of the finely honed skills that helped keep officers and the public safe prior to February 2020 will have eroded from a lack of use, and it will be incumbent upon agencies and officers alike to undertake these returns to normalcy with serious and deliberate caution. -

2021-04-05

2021-04-05Online Article: ‘Burned out’: Portland cops leave scathing exit interviews

This article from Oregon Live/The Oregonian was picked up by Police1, and it discusses a number of exit interviews that retiring and resigning Portland Police Bureau officers, detectives, and administrators left during the past year. Of particular interest is the section that discusses the story of Jaykary Jackson: "Young officers of color have left, including Jaykary Jackson, who went to Boise, and Elise Temple, who was one of the Police Bureau’s recruiters. Temple declined to comment on the record. Jackson didn’t respond to messages but he was one of the officers who spoke out last summer about being on the front line of racial justice protests as an officer with the Rapid Response Team. A graduate of Portland State University who joined the Police Bureau after working for Nike for 10 years, he said then that he became a cop because he “wanted to make the most out of my life by helping others.” He also was following in the footsteps of his father and aunt. But Jackson said he was disgusted by the hatred he and other officers faced while standing on the police lines. He got hit by an explosive one night, felt tingling in his fingertips and heat from the device, and got berated by young white protesters. Often when he tried to talk to someone of color at the protests, he said, “Someone white comes up and blocks them and tells them not to talk.” Or yells, “Eff the police ... don’t talk to him.” He left shortly after he was named to be a new community engagement officer." The article illustrates the additional concerns that officers in major cities and law enforcement agencies face, especially when their civilian oversight overwhelmingly seeks to placate protests with emotional vindication in lieu of reasoned, rational, and planned reforms. -

2021-04-05

2021-04-05Online Article: Law enforcement officers need to be proactive in self-care to ensure they are resilient in the midst of loss and trauma

This article discusses guidance for law enforcement professionals to adopt better self-care practices through this pandemic and the increased volume of vicarious trauma, depression, anxiety, and suffering prevalent in our societies. The author specifically addresses the problem of police suicide, which is often committed at similar rates to military combat veterans. While the article's content helps officers potentially deal with the difficulties of their calling, it might also help the public better recognize the darker and unwelcome realities of police work. -

2021-01-15

2021-01-15Retired Oakland cop attended US Capitol riot, OPD internal affairs investigation underway

A former Oakland police officer has received a visit from the FBI. Jurell Snyder tells the ABC7 I-Team, agents interviewed him about attending last week's Trump rally that led to the assault on the Capitol, and about his social media posts promoting conspiracy theories. Some current Oakland police officers liked and commented on Snyder's posts, and now, the department is investigating those officers. -

2021-01-16

2021-01-16Guard troops deployed throughout downtown Sacramento in advance of expected violence

California National Guard troops were deployed throughout downtown Sacramento early Saturday in advance of expected protests and violence that the FBI warns could last through Inauguration Day. At the state Capitol — which is expected to be the site of protests Sunday and Wednesday as well as unrest between supporters of President Trump and antifacist groups — armed soldiers, Guard trucks and armored Humvees were stationed on streets around the building. Soliders and vehicles were positioned around other buildings, including the federal courthouse and the Superior Court building, as well as the Leland Stanford Mansion and buildings along Capitol Mall. -

2021-03-29

2021-03-29Senior Border Patrol officer says border migrant flow will only worsen

"Senior officer says border migrant flow will only worsen" By Lyda Longa, lyda.longa@myheraldreview.com, Mar 29, 2021 The situation with undocumented migrants flocking to the Southwest border of the United States from Mexico is only going to worsen, a senior Border Patrol agent warned Friday. The agent, who spoke to various media outlets during a conference call, said at least 380,000 undocumented people had been apprehended at the Southwest border in February and the numbers would be higher for March and beyond. The agent spoke on background with the agreement that media would not reveal his name. “I fully expect to see the numbers increase as we go into the summer months,” the senior agent said, concerning migrant crossings. In Cochise County that warning has begun to bear out near Douglas and in Willcox, where the already stretched-thin Border Patrol is arresting more single adults attempting to slip into the country or taking in and processing children who are flocking to the border unaccompanied. Douglas Mayor Donald Huish said Friday the latest information he received this week from Border Patrol agents at the station just outside Douglas is that they’re confronting and repatriating about 100 single adults daily who are trying to slip in illegally. “They are getting closer and closer to town,” Huish said. What concerns Huish even more is that Border Patrol agents from the Douglas station are being pulled out to help in busier areas such as Yuma and Tucson. “They’re siphoning them off to the western part of the state and leaving us with a skeleton crew,” Huish said. In Willcox, Mayor Mike Laws said he was told two weeks ago by the Border Patrol there were 54 unaccompanied children at the Border Patrol station. “That was two weeks go. Who knows now?” Laws said. “The station can only hold up to 81.” Laws said he was told by Border Patrol that a “third party” has been arriving at the facility and taking 10 to 20 children to Phoenix by via bus. The mayor said he does not know how often the transportation comes or who the third party is. “We have not seen anyone (undocumented migrants) running the streets so far,” Laws said. “All we have is the youths, but we don’t see them either.” Laws and Sierra Vista Mayor Rick Mueller said citizens in their respective communities would gladly help the undocumented migrants but there aren’t enough resources available to do so. Laws, Mueller and other mayors in Cochise County signed a letter recently asking the federal government for help with the matter. Last week, the town of Gila Bend, which has a population of about 2,000, declared an emergency after Border Patrol agents dropped off a group of migrant families with children in a park. Gila Bend Mayor Chris Riggs told reporters he and his wife ended up using loaned vans to drive the families to the Phoenix Welcome Center so they would have a safe place to stay. Riggs said Border Patrol agents told him to expect more of the same. Mueller said there have been no such issues in Sierra Vista, but he is worried that the municipality, if hit with something similar to what happened in Gila Bend, would have no resources to offer. Last week Arizona senators Kyrsten Synema and Mark Kelly announced they’ve been pushing for more federal resources to help Arizona cities with a sudden influx of undocumented migrants. The senators helped secure at least $110 million from the Federal Emergency Management Agency as reimbursement to cities that assist migrants left within their jurisdictions. Also last week, Arizona Gov. Doug Ducey and Florida Senator Rick Scott — who sits on the Homeland Security Committee — called on President Joe Biden and Department of Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas to visit the Southwest border. Ducey and Scott, accompanied by a handful of law enforcement and other elected officials, had toured a portion of the border near Douglas. At his first press conference on Thursday since taking office in January, Biden said he would come to the border soon, but thought a visit now would deflect attention from the issue at hand. The senior Border Patrol agent who spoke Friday, meanwhile, said 300 Border Patrol agents who work along the northern border of the U.S. have been “mandated” to the Southwest border to assist with the influx of migrants. He said about 2,000 family units out of the 6,000 who are trying to cross daily are being processed in Texas by the Border Patrol. The agent revealed that unaccompanied children are being kept in Border Patrol facilities longer than the 72 hours established by law because too many are showing up and agents are overwhelmed. “They’re keeping them a few days, sometimes up to a week,” the senior agent said. Once an unaccompanied child is encountered, Border Patrol contacts the Department of Health and Human Services. The latter makes arrangements for the migrant children to be taken by the Office of Refugee Resettlement. The agent also mentioned an increase in the criminal element among undocumented migrants. “The threats we see are significant,” the senior agent said. “We have seen criminal (undocumented migrants).” Additionally, he said that COVID testing for migrants is only being done in facilities in Del Rio, Texas, and soon in the Rio Grande Valley in Texas. Other than that, testing is being undertaken by non-governmental agencies that are helping the migrants and U.S. Immigrations and Customs Enforcement officials. He said it was probable that some migrants with COVID-19 may have been released into communities. -

2021-02-24

2021-02-24Rate of Coronavirus Cases Among LAPD Officers Plummeting; Mass Vaccination Slated to Begin Next Week

This article discusses the decline in COVID-19 infection rates among LAPD employees and personnel as their vaccination rates increase. This expected correlation demonstrates the efficacy of the early vaccines despite ongoing concerns at that time about an increasing frequently and number of viral variants across the United States. Additionally, the article addresses concerns of officers who choose not to get vaccinated. At the time of this article, 8 LAPD employees had died from COVID-19 complications and, at one point, more than 20 were testing positive with new infections each day. Those infections have dwindled to about 30 per week, and are likely also a reflection of vaccination among the general population as well as among police officers. -

2021-02-02

2021-02-02Southern NM County Mandates COVID-19 Vaccine for First Responders Including Sheriff's Deputies

This article discusses a recent mandate from the Dona Ana County government, which is seated in Las Cruces, New Mexico, that orders all its first responders to submit to vaccination. To my knowledge, this is the first such mandate in the United States, and it illuminates the relative lack of control first responders have over their lives once they enter their respective profession. The order is likely to be contested, particularly when such requirements have not historically been a condition on employment, The order reads in part, "Being vaccinated is a requirement and a condition of on-going employment with the County due to the significant health and safety risks posed by contracting or spreading COVID-19." The order applies to all paid personnel in the county's law enforcement, fire, detention, and medical professions. -

2021-03-24

2021-03-24COVID-19 Claims Life of Trailblazing Bourne Police Lieutenant, Cancer Survivor

The COVID-19 pandemic continues to affect law enforcement personnel far more than all other job hazards. The SARS-CoV-2 virus killed more American police officers and law enforcement personnel in 2020 than any other cause of death, and that trend appears to continue in 2021. Unlike most other essential workers, law enforcement professionals cannot reliably keep social distance or avoid personal contact with the public and their colleagues. Additionally, they are unable to seek reasonable accommodations that would allow them to do so, and their failure to fulfill their duties and sworn obligations is often grounds for dismissal and decertification. -

2021-03-21

2021-03-21Oral History: Interview with Anonymous Peace Officer #2

James Rayroux 0:01 My name is James Rayroux, and I'm a graduate student in global history at Arizona State University, and I'm working as a curation intern with the "Journal of the Plague Year" COVID-19 archive. Today is March 21, 2021, and it's just after 8:12pm or 2012 hours here in Arizona. I'm speaking with a narrator who wishes to contribute to the COVID-19, archive anonymously. Sir, I first want to thank you for speaking with me and contributing to this COVID-19 archive. Do you consent to having this interview recorded, transcribed, and immediately posted to the "Journal of the Plague Year" COVID-19 archive, where it will be made accessible to the public? Anonymous Officer 0:43 Yes, I do. JR 0:44 Thank you again for agreeing to speak with me and making time for this interview. In lieu of your name, or location, can you provide a summary of your background and professional experience in law enforcement? AO 1:01 Sure, I've been sworn law enforcement for almost 23 years in a state in the Rocky Mountain region. I've worked both for municipal and state government, and I work for small to medium sized agency now about 35 sworn officers. I'm a military veteran, I was US Navy prior to my time prior to going to the police academy, and I worked a variety assignments from patrol to drug and alcohol enforcement, auto theft Task Force, Joint Terrorism Task Force, supervision, criminal investigations, and command. JR 1:44 During that time what are some of your most prominent or important achievements within the law enforcement profession? AO 1:54 You know, I think that this profession, namely, is typically not about the individual. I would probably point towards successes in the community and successful team building and successful growth of individuals into the business. I think one of my most proud achievements I think, something I'm tremendously, I feel tremendously accomplished for is somehow I failed to convince my son to be a firefighter, and he was just sworn in at another municipality in the same state as a sworn law enforcement officer. So while I have failed him and trying to convince him to do literally anything else, I'm also extremely proud and accomplished that I have raised my son into a similar professional lineage, and he's elected to take the oath to protect his community, as well. JR 2:57 What are your current roles or assignments within your organization? AO 3:04 I'm currently assigned as a patrol supervisor, a watch commander. I supervise a shift of a number of police officers and currently working day shift. So in those roles, I'm essentially the emergency manager for our smaller community, supervise police response to emergencies, meet with the public, interact with command staff, meet with public stakeholders, and then, essentially, a customer service rep who happens to be a sworn law enforcement agent. JR 3:37 When and how did you learn about the SARS-CoV-2 virus in early 2020, and what were some of the first conversations you remember having about it at work? AO 3:51 So COVID became on the tip of everybody's tongue probably in early January. And previously, in the end of 2019, it was somebody else's problem. It was, it was a China problem, it was a Wu Han problem, specifically. It was, it was out of sight out of mind. And, of course, you'll know this about law enforcement, there's only two kinds of problems in law enforcement, those being "my problem," and "not my problem." And during the first part of 2020, it wasn't our problem. There was a limited amount of cases in the US, they trickled in. Most of what we understood about the virus that causes COVID-19 was based on the media, was based on, you know, what you might catch a snippet of on NPR on Fox News, which has no news about foxes, I might add, and essentially, just the snippets we would get on the media and I don't remember having official tangential conversations about the COVID-19 virus in a strategic way, until probably February. A lot of those initial conversations, you know, as, as trained observers and trained investigators, I know many, many law enforcement officers who don't immediately give a lot of trust or credence to things their government tells them. So, for the first little while, it was kind of an attitude of scrutiny, one of a lack of credibility. We weren't really sure whether this was hype and whether there was really any risk, and there was a lot of conversations about the corollary between, you know, the standard flu and other illnesses that killed just as many if not more people, and there was a lot of disagreement about their trajectory, and the volume, and the scope, and really how this thing was going to manifest. JR 6:04 How did your agency first deal with the COVID-9 pandemic in an official way? AO 6:12 The first steps that were taken initially, mostly just surrounded, strategic outward facing changes to how we did business on the street, basic social distancing, wash your hands, don't touch your face, basically just mimicked CDC advice. You know, be careful more to come. Very low level, very basic, no real operational changes, no testing, no recommendations for symptoms that was, you know, under the umbrella of "flatten the curve," keep yourself healthy sort of jargon, that was shared from both the government and from the administration of our, our small community downwards towards the police department and other, other trades in the region. JR 7:13 What did your first pandemic briefing or roll call look and feel like after those changes were made? Where you and your squad entirely in masks for that first time, or was that yet to come? AO 7:29 When the government of our state first mandated masks, there was specific legislation that excluded law enforcement. It was quickly decided that masks were recommended, but were not required initially. So there was this sort of juxtaposition and feeling out period in our community where not a lot of people wore masks. It was recommended. You were supposed to wear them when you were outside, you were supposed to wear them, you know, when you were in contact with others. The science hadn't really been affirmed. There weren't a lot of links to credible research yet. And, of course, a pandemic of this nature has never been experienced or dealt with for generations previous to this. And so, you know, I'm 100% cofident telling you that literally everyone was just winging it, and that was immediately apparent in that first briefing where we discussed what we were going to do. Still scrutiny, still somewhat lack of credibility, lots of, lots of eye rolling with a few critical and strategic thinkers, you know, raising, you know, what would later be the first semblance of some alarm, saying, "Hey, you know, maybe, maybe this is going to be a big deal. Maybe we haven't experienced anything like this before, we ought to be as careful as possible." JR 9:03 How did your agency's policies and procedures change over time after that initial effort? AO 9:13 So the, you know, the, the tide came in, in a big way very quickly. And as you'll remember, as the COVID-19 virus, sort of sieged Italy and New York and the Eastern Seaboard, everybody started paying attention in a big way. And we're, you know, a couple 1000 miles from there, but local and state governments started reacting very, very quickly. Masks were mandated for all persons in contact with the public. A scramble was afoot to obtain PPE [personal protective equipment], which supply chains being, you know, any resemblance of the way they were in 2019, there was no problem. You just got on Uline or Amazon or, you know, you know, whoever your main commercial supplier was, and you ordered them by the skid and PPE was readily available and there was no reason to hoard it. But all of a sudden, there weren't any. There wasn't any, the supply chains were just curb-stomped into this sort of perpetual waiting period where nobody was sure what they were going to need, and everybody thought that N-95 respirators were the new hotness, and everyone had to have some from car dealers to people working the drive thru to baristas to, you know, the guy doing my front end alignment. So all of a sudden, we were trying to balance what was practically happening on the street, what our day-to-day call volume looked like, and what we were really supposed to do with the PPE we had knowing that our resupply was probably distant. And when we wove all that together and put all that minutia in a pot and stirred it up, what we came up with was pretty much this overwhelming sense of nobody knowing anything that was reliable. And it was anybody's best guess how long this was going to last and what we're going to need. That was echoed among our local hazmat [Hazardous Materials responders], our local health departments, our local health organizations. Nobody had any PPE to give us, nobody knew how long it was going to last, and nobody could have any real recommendations except for this sort of parroted, you know, don't touch your face, wash your hands, wear a mask in contact with everybody. Once masks were required, we had some pretty significant changes to the way that we did business in the community. You know, as a forward facing law enforcement agency, we contact, you know, one officer might contact 10s of people every day, sometimes might make 15 or 20 contacts before, you know, the afternoon's said, and by doing so, what we know now to weave a fabric of a contact trace that is essentially impossible. I mean, we remove Degrees of Separation all day long just by talking to people. And none of that technology and contact tracing and science had really entered the social jargon. But we were out there just trying to be as careful as possible, and it wasn't until probably...probably late March is when you know rivers turned to blood and the sky fell as far as the government was concerned. And it was then that definitive, codified changes were made to procedure where there was a moratorium put on traffic enforcement and all proactive street contacts, except for egregious emergency violations. We didn't make traffic stops for weeks. There was a moratorium immediately placed on warrant arrests and on booking people at the jail because, having a potential infectious patient in your vehicle, nobody knew what the consequences of that were or how to decon [decontaminate] it. So we didn't arrest anybody. If it was a crime of violence, or a crime against a person with a victim, we would screen it at the jail first. Everybody warned N-95 mask, and we would transport them as quickly and safely as possible. If it was a warrant for anything nonviolent, warrant for bench warrants, and courts and anything, we just let them go. Even if somebody told us that they had COVID symptoms, or were COVID positive, there was still no viable testing in the system, and no way to confirm or deny that those statements were true so we didn't book them. So many suspects in cases either went uncontacted, cases were dismissed, or the warrants were skipped just because the precautions weren't in place yet, and the agency and all the businesses and other agencies we worked in the region were trying to just to stay healthy. Proactivity probably took a, I think, I would call a permanent shift. I have not seen a resurgence of practice enforcement and the likes of which I might like. Cops just stopped doing business the way that they used to, and some of the badges we'd wear and some of the honor that we took in protecting the community came from making contacts: suspicious vehicle, suspicious people, you know, local transients, patrolling, you know, bike racks and stealing cars and stealing bikes and harassing people and it, it turned into kind of this proactive wasteland where law enforcement was worried about exposing themselves. They were worried about exposing each other. They were worried about exposing their families. And they were worried that if they happen to make a contact, they might expose the next people, the next 10 or 15 people that they talked to that day. So the only way to eliminate that was just to stop doing it. So by eliminating, you know, the patient zero style traffic stops, we hoped to have an impact on that, and flatten our own curves by just not talking to anybody unless it was an emergency. JR 15:38 Do you remember the first call or the first contact that you went on where you and the public were both wearing masks? AO 15:51 I don't remember it specifically. But I remember a handful of contacts that were made in right around March when, you know, when I said that when the king tide came in with news and with panic and fear. And I remember a handful where nobody really was sure what to do. Everybody was, had this sort of weaponized social distance, and people would walk the other direction when you tried to talk to him, and we hadn't mastered the, you know, the little elbow bump or the little nod, and so nobody could figure out how to talk to one another, and there was quite a few instances of the COVID card being played where people just simply didn't want to talk to the police. So they, they feigned fear and panic for exposure and wouldn't come out of their homes and open their car doors or their windows. And then shortly thereafter, it became socially stigmatic to participate in the fear and panic. And if law enforcement didn't wear masks, we sort of became this pariah immediately. So it was, it was optional for a very short period of time, but then very, very quickly, virtually every single contact we made had to have a mask on, of course, which, you know, brings with it all the problems associated with not being able to see somebody's face. It's hard to hear, it's hard to talk on the radio. It's hard to smell intoxicants, you know, it just added sort of this, it was basically like dimming the focus one click on your whole world by having to cover your face. But, you know, at that point, some of the science was starting to become more consistent and more published, and every, most everybody at that point was pretty convinced that at least when in contact with the public and the unknown, that some sort of mask was viable and necessary. JR 17:50 In Western society, handshaking has long been a very important social event. And that's obviously gone by the wayside with the general public since the pandemic began. In lieu of having that physical contact to make direct human connections, how have you tried to establish rapport with the public when you do have to contact them? AO 18:21 It's been weird. You know, handshakes have been sort of the status quo of a show of respect and humility for so many years. I mean, you know, you hold your hand out, it's almost instinctual. It's almost primordial. You know, in this culture in Western culture, someone holds your hand out, and you don't take it, like, them's are fighting actions, right? So it's, it was weird. We had to figure out ways to break the ice, we had to figure out ways to do that acknowledgement, and I'll answer it two ways. The first way was we had to figure out how to communicate with people even though they couldn't really see our faces, and there could be no sort of context to breaking sign of respect, like the handshake. So you know, you come up with this weird elbow bump, or you give the little, you know, the little nod that one bro gives to another across the urinal, and you find out ways to just break the ice with people. And the second challenge that we experienced was that we could no longer show those signs of respect to one another in view of the public. So if one cop was touching another, or, you know, giving a little handshake or playing grab ass, or high five, or even just a fist bump, all of a sudden, we were cast out, right? All of a sudden, those little, that that lack of social distancing became this socially virtuous thing to exploit and to ridicule, and so we had to be exceptionally careful in public even though within shifts, we considered our shifts to be close contact circles. I mean, any sworn law enforcement officer working during the COVID shutdown very likely saw their shift mates more than they saw their blood families. And so there was just no way to socially distance internally at work, because of the, just close knit manner in which the job is done and the proximity we had to one another throughout the day. Yet in public, you know, we're in our own cars we're socially distanced, we got to have masks on, you better boil yourself between each contact, and you got to wear booties and a Tyvek suit and touch everybody with a little wand. And in the mix, I feel like our isolationism increased, and I feel like our bonds of society from a law enforcement perspective became even more tenuous. So, you know, one of the things I adopted was I started using my first name with everybody. I stopped using rank, I stopped using identifiers. I just told him who I was. I asked them for their first name, I use my first name, I tried to break it down. And I would always, you know, have these little catch conversations I do and I introduced everybody, and just try to acknowledge that this is a new time and, you know, you hear in the media and you see it a lot. And in every, every, you know, corporation, commercial for six months, it was, "in these trying times." So, that sort of became the catchphrase like, "Hey, in these challenging times, things are different. Here's the business I'm here to do. My name is so-and-so. We're trying to keep the peace, how can we be helpful?" And we interacted with all kinds of people. Some people thought it was a hoax. Plenty of, plenty of sovereign citizen scam-demick, plan-demick jargon being thrown our way. And then on the other side of that spectrum, were extremely scared, extremely isolated...people wouldn't come out of their houses, people were afraid to take a Grubhub delivery. People were, you know, boiling their utensils. And somewhere in the middle, law enforcement just kind of figured out a way to break the ice, and I think it's, I think it's going to be permanently different. And I can tell you that because the day before yesterday, I was on a burglary call where I talked to the informant. Without even thinking, I reached my hand out to shake his hand because he told me his name. He said, "Hey, thanks for coming. I'm so and so." And without even thinking about it, my mammal brain shot my hand out in a greeting. And it took him about five seconds of staring at me before I figured out that we just don't do that anymore. And it's super weird, but we, we're working around it. JR 22:51 What do you miss most about your job or your daily work duties from 2019? AO 23:02 You know, I don't know if this is going to be directly related to the pandemic. I think that in 2019, we were dealing with a community that understood what the rules were. Everything was, you know, we call it "pre-COVID," we call it "olden days," I don't know if we're ever going to return to those times, but cops are out there doing business in the community, and we were fighting crime and protecting people. And we were making this self sacrifice and serving our community and being forward facing and just eatin' meat and just leaning in just to get business done. And we did it no way that served our customer and served our client base. And I don't know any law enforcement officer who's been on the job for more than 10 minutes who doesn't do this because they love the community they work, or they love the service that they provide, or the people they protect. And I think we've permanently changed the way that law enforcement officers are viewed by their communities. I think we've done, and I say "we," I mean we as a culture, good, bad, or indifferent, have done irrevocable damage to the reputation of law enforcers in our community and the public trust that they must hold in order to be successful. And then all of a sudden, the communities "why nots" became really, really strong. And cops had to start making excuses really quickly about why we weren't the bad cops. And why we weren't doing this to violate your civil rights. And why we're just, we're just out there trying to do the job and just trying to, you know, serve policy and serve the constitution and it might not be about you and your mask. And I feel like this stigma, the social stigma became leveraged against law enforcement in a really big way without any real underlying facts. No one, you know, it just became this sort of socially virtuous stigmatic status to hate the cops, whether it was for their efforts to preserve the public peace in the pandemic, or whether it was your interpretation of their worth based on events taking place in the national landscape. It became cliche to hate the cops. And I think I miss, I missed the real relationships we had in 2019 that were based on sort of a shared respect, and a common understanding and actual virtues of character and integrity. And now, you know, it's, it's an uphill climb. We're sort of this Sisyphussian rock-pushing force, just always trying to push this public opinion and public trust rock up the hill only to, you know, take two steps back, and I miss that quite a bit. JR 26:15 What do you wish that the public understood about law enforcement during the COVID-19 pandemic? AO 26:27 I think if I could choose one thing, I wish that the public understood that nothing changed in the way that law enforcement supports and loves and wants to collaborate with the community. During the pandemic, law enforcement was shined in three or four different colored lenses varying from, you know, rosy to catastrophic, and most police officers on the street during the pandemic, were humans just trying to figure out how to navigate their space and provide for their families, and to continue to protect the public and somehow navigate shark infested waters of this, the sudden unknown COVID-19 enemy. And it was a huge struggle, you know, policy was changing on the daily. Science and procedure was being released several times a day at, you know, at its busiest, and most law enforcement were just caught in the wake of this rapidly changing information, hugely volatile work environment, and trying to keep themselves and their families healthy while still being effective. I wish the public knew how much most law enforcement officers hate racism and prejudice and corruption. I wish they knew that nobody hates dirty cops more than we do. And that virtually all the law enforcement officers they contact on the daily are still doing the job because they've considered the risks to their lives and their risks to their health and the risk to their family's health, and are still willing to suit up every morning or every night, and put body armor on, and put 30 pounds of gear on, and go out there and risk their health and safety to protect our community, and mostly people they don't even know and have never met. And I think that's what's really at stake when the rhetoric gets really loud and the disinformation gets really deep. And the panic and the fear really starts to grab older people is they start to lash out against the government as a whole and what they don't understand in, you know, in some way is that that uniform represents just another member of their same community who is trying to stand between the two entities and make good decisions, and protect the constitution and uphold the peace and protect the, you know, the victims and protect, you know, the weak from the oppression and you know, all the things we stand for. But all those cops out there are just the same community members. Some of them don't have any toilet paper at home. Some of them couldn't buy peanut butter. Some of them didn't have fresh food for weeks because they couldn't go to the grocery store because of their shifts. So it wasn't that there was this divide. It wasn't that there's this this pantheon of law enforcement officers who were out there trying to screw everyone, it was members of the very same community who just happened to put that uniform on by choice to save it and protect the community despite the fact that there was this, you know, this crazy pandemic and all the fear and panic going on at the same time. JR 29:56 Knowing that I intended to speak with you about law enforcement and your experience in that profession during this pandemic, what, perhaps, was one of the questions that you hoped to answer or that I didn't ask? AO 30:18 One of the things I was thinking about talking about was that, for the first several weeks, I would say maybe even two months, there was no viable testing for any first responders in our region. So if one of my guys or gals was symptomatic, they simply had to be quarantined, and there was no way to test. We begged and borrowed and pled, and, you know, by hook or by crook, tried to figure out how to make a relationship with a clinical entity so that we could protect our people and keep them in place and keep them effective and keep them assigned on the street. What happened was any flu-like symptoms were just viewed as COVID quarantine, and so there was a couple of days there where I almost didn't have an emergency dispatch center because I didn't have anybody to work. There was a couple of days where we were hemorrhaging overtime money paying the cops that were healthy to cover the cops that were not because we couldn't get them tested. It took quite a while until we had a viable, and until the turnaround was fast enough that it was sustainable to test people. Because if the turnaround was 10 days, and the quarantine was 14 days, and almost was you know, half a dozen, six of another, you were gonna stay home anyway. So until the testing was fast enough and efficient enough, we burned a lot of time, and a lot of cops sat at home for 14 days under quarantine who maybe didn't mean to, and there was no way to test them. Once testing was viable, and available, I feel like we did a better job of that. But at the beginning, there were several of us who were pretty sure we had contracted the virus and suffered its effects as early as January or February, a ton of us were sick in January and February and early March before, way before viable testing was available in our communities. And that was, that was a challenging and an alarming period of time where even my first responders we just didn't know. And if you weren't admitted to the ER, if you weren't seen clinically, and if you didn't have co-morbidities or other risk categories, you just didn't get tested because the resources didn't exist. And why would we waste a test on a first responder who can just quarantine for two weeks and be otherwise healthy when we need to use it on, you know, the septuagenarian co-morbid patient who's, you know, got 15 different ailments, and I understand that math. But it was pretty frustrating to just have to hemorrhage overtime money and just suffer and figure out how to cover shifts and work 16, 18 hours in a row because there just wasn't anybody else. JR 33:23 I am incredibly grateful for your time and for sharing your expertise and your thoughts with us. Thank you so much. AO 33:31 You're very welcome, sir. Thank you for the opportunity. Transcribed by https://otter.ai -

2021-03-20

2021-03-20Oral History: Interview with Anonymous Peace Officer #1