Item

Amanda Wong Oral History, 2021/05/12

Title (Dublin Core)

Amanda Wong Oral History, 2021/05/12

Description (Dublin Core)

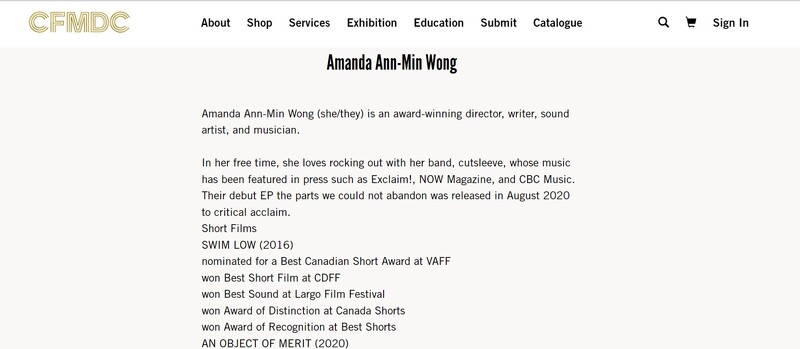

Self Description: “My name is Amanda Wong. I am a member of the band cutsleeve. We are an all queer, East Asian, alt-rock band, based here in Toronto. On the side I am also a filmmaker and a sound artist. I am an immigrant here to Canada; I moved here when I was 12.”

Some of the things we spoke about included:

Funding for the arts during the pandemic

Comparisons and contrasts with the response to SARS in Singapore witnessed as a child and what is being witnessed now with COVID-19.

Difficulties accessing health care outside of the context of COVID-19

The inadequacies of mental health care access in Canada

Freelance work

Recording cutsleeve’s first EP during the pandemic

What it was like to work on a film set in the earliest stages of the pandemic

Anxieties about any cold- or flu-like symptoms

Cancelling birthday celebrations because of the pandemic, just before the shut down. How little anyone knew at the beginning about transmission, and the fear that comes from that.

Cancelled planned travel to Asia to visit family in Feb 2020.

Nesting as a part of spending so much time in the home.

The disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on certain groups: immigrants and people of colour.

Reduced contact with partner, under the pandemic seeing one another only once a week. The difficulties of them both having roommates and what that meant for risk taking.

How having a car determines testing access.

A friend having gotten COVID.

Contrasts between Western and Eastern ideas and values in medicine.

The Canadian government’s treatment of Black and Indigenous Peoples

Anti-Asian racism terminology

Creating anti-oppressive atmospheres of safety at concert venues

Realizing the harm of some pre-pandemic norms.

Remembering one has a body.

Other cultural references: the board game Pandemic, NyQuil

Funding for the arts during the pandemic

Comparisons and contrasts with the response to SARS in Singapore witnessed as a child and what is being witnessed now with COVID-19.

Difficulties accessing health care outside of the context of COVID-19

The inadequacies of mental health care access in Canada

Freelance work

Recording cutsleeve’s first EP during the pandemic

What it was like to work on a film set in the earliest stages of the pandemic

Anxieties about any cold- or flu-like symptoms

Cancelling birthday celebrations because of the pandemic, just before the shut down. How little anyone knew at the beginning about transmission, and the fear that comes from that.

Cancelled planned travel to Asia to visit family in Feb 2020.

Nesting as a part of spending so much time in the home.

The disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on certain groups: immigrants and people of colour.

Reduced contact with partner, under the pandemic seeing one another only once a week. The difficulties of them both having roommates and what that meant for risk taking.

How having a car determines testing access.

A friend having gotten COVID.

Contrasts between Western and Eastern ideas and values in medicine.

The Canadian government’s treatment of Black and Indigenous Peoples

Anti-Asian racism terminology

Creating anti-oppressive atmospheres of safety at concert venues

Realizing the harm of some pre-pandemic norms.

Remembering one has a body.

Other cultural references: the board game Pandemic, NyQuil

Recording Date (Dublin Core)

May 12, 2021

Creator (Dublin Core)

Kit Heintzman

Amanda Wong

Contributor (Dublin Core)

Kit Heintzman

Link (Bibliographic Ontology)

Controlled Vocabulary (Dublin Core)

English

Music

English

Healthcare

English

Health & Wellness

English

Race & Ethnicity

Curator's Tags (Omeka Classic)

altrock

art

artist

Anti Asian Hate

Asia

Asian

Canada

East Asian

Eastern medicine

film

freelancing

grants

immigrant

musician

Ontario

performing arts

partnership

queer

rock

roommates

selfcare

SARS

safety

Singapore

testing access

Toronto

travel

Contributor's Tags (a true folksonomy) (Friend of a Friend)

SARS

artist

Canada

mental health

Asian

racism

Collection (Dublin Core)

Asian & Pacific Islander Voices

Date Submitted (Dublin Core)

12/18/2021

Date Modified (Dublin Core)

03/03/2022

05/23/2022

01/15/2023

04/06/2023

05/12/2023

Date Created (Dublin Core)

05/12/2021

Interviewer (Bibliographic Ontology)

Kit Heintzman

Interviewee (Bibliographic Ontology)

Amanda Wong

Location (Omeka Classic)

Toronto

Ontario

Canada

Format (Dublin Core)

Video

Language (Dublin Core)

English

Duration (Omeka Classic)

01:14:08

abstract (Bibliographic Ontology)

Some of the things we spoke about included:

Funding for the arts during the pandemic

Comparisons and contrasts with the response to SARS in Singapore witnessed as a child and what is being witnessed now with COVID-19.

Difficulties accessing health care outside of the context of COVID-19

The inadequacies of mental health care access in Canada

Freelance work

Recording cutsleeve’s first EP during the pandemic

What it was like to work on a film set in the earliest stages of the pandemic

Anxieties about any cold- or flu-like symptoms

Cancelling birthday celebrations because of the pandemic, just before the shut down. How little anyone knew at the beginning about transmission, and the fear that comes from that.

Cancelled planned travel to Asia to visit family in Feb 2020.

Nesting as a part of spending so much time in the home.

The disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on certain groups: immigrants and people of colour.

Reduced contact with partner, under the pandemic seeing one another only once a week. The difficulties of them both having roommates and what that meant for risk taking.

How having a car determines testing access.

A friend having gotten COVID.

Contrasts between Western and Eastern ideas and values in medicine.

The Canadian government’s treatment of Black and Indigenous Peoples

Anti-Asian racism terminology

Creating anti-oppressive atmospheres of safety at concert venues

Realizing the harm of some pre-pandemic norms.

Remembering one has a body.

Funding for the arts during the pandemic

Comparisons and contrasts with the response to SARS in Singapore witnessed as a child and what is being witnessed now with COVID-19.

Difficulties accessing health care outside of the context of COVID-19

The inadequacies of mental health care access in Canada

Freelance work

Recording cutsleeve’s first EP during the pandemic

What it was like to work on a film set in the earliest stages of the pandemic

Anxieties about any cold- or flu-like symptoms

Cancelling birthday celebrations because of the pandemic, just before the shut down. How little anyone knew at the beginning about transmission, and the fear that comes from that.

Cancelled planned travel to Asia to visit family in Feb 2020.

Nesting as a part of spending so much time in the home.

The disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on certain groups: immigrants and people of colour.

Reduced contact with partner, under the pandemic seeing one another only once a week. The difficulties of them both having roommates and what that meant for risk taking.

How having a car determines testing access.

A friend having gotten COVID.

Contrasts between Western and Eastern ideas and values in medicine.

The Canadian government’s treatment of Black and Indigenous Peoples

Anti-Asian racism terminology

Creating anti-oppressive atmospheres of safety at concert venues

Realizing the harm of some pre-pandemic norms.

Remembering one has a body.

Transcription (Omeka Classic)

Amanda Wong 00:01

Hello

Amanda Wong 00:01

Hello.

Kit Heintzman 00:04

Would you please start by telling me your full name, the date, the time and your location?

Amanda Wong 00:09

Yeah, my name is Amanda long. The date today is May 12, 2021. And I am located in Toronto, Ontario.

Kit Heintzman 00:21

And did you say the time or did I miss it?

Amanda Wong 00:24

I didn't, because I'm totally missed it. My lack of focus my ADHD. It's Wednesday, the 1:48pm. Right now, currently.

Kit Heintzman 00:38

And do you consent to having this interview recorded, digitally uploaded and publicly released under Creative Commons License attribution noncommercial sharealike?

Amanda Wong 00:49

Yes.

Kit Heintzman 00:50

Thank you. I'd like to just start by asking you to introduce yourself to anyone who might find themselves listening to this what would you want them to know about you and the context you're speaking from?

Amanda Wong 01:02

Yeah, so my name is Amanda Wong, and I am a member of the band cut sleeve. We are an all queer, East Asian art rock band based here in Toronto. And I on the side, I am also a filmmaker and sound artist and I am an immigrant here to Canada. I moved here when I was 12. And I guess that's it. I'm trying to think about any other interesting or things that would pertain to this, but I think we'll go with that for now.

Kit Heintzman 01:44

What do you what just the word pandemic, conjuring you when you hear it?

Amanda Wong 01:51

The word pandemic we talking about now, or pre COVID?

Kit Heintzman 01:58

Oh, I'd love to hear about both.

Amanda Wong 02:00

Um, I think before COVID I, I didn't really think much about the word out to be honest, I would not be able to know the difference between epidemic or pandemic or the other dynamics or, and I do know that there is a board game called pandemic. And I you know, I, I lived in Asia during the time of SARS. So, I also have experience with that. So, I would probably think about SARS. Although, you know, it was not anywhere near the level of what this is the you know, COVID-19 is now and then after sort of COVID-19 started taking over the world. I when I hear pandemic I think about the all the other associations that come along with it the lockdown the staying at home, the numbers of people that have died from anti vaxxers people who deny that it exists. But then also these, you know, these factual things, but also, you know, sort of the emotional aspect behind it of people being isolated and lonely and people losing their loved ones and not being able to, like visit them at you know, when, when they're in the hospital or when even in like a funeral, you know, you can't even hold a funeral anyways, those conjure up it's the word pandemic conjures up all this sort of like images for me, but also, I think, like I personally received a lot of support during the pandemic, from organizations and from others. So there's also that sort of positive aspect to it, that I think that we also found ways to still be social with each other with with each other, beyond, you know, sort of in person meetings and, and the amount of support that communities have sort of put back into giving back to their community. And, you know, I was I even received a grant to make a film during the pandemic. It was called immured queer emergencies by the Toronto Queer Film Festival. So there's a lot of like, you know, really good work that is happening during the pandemic. But so a little bit of both of you know, not so great, but great stuff. When you say, pandemic.

Kit Heintzman 04:20

Would you be willing to share a bit about what you remember about experiencing SARS?

Amanda Wong 04:27

Yeah, I mean, I was quite young during SARS. I was so I was How old was I? I was probably around eight or nine when SARS happened. SARS was like 2002-2003. Right? If I'm not wrong, so around that age, and I lived in Singapore at the time and we in school We were all given out. Each school child was given a free thermometer, an oral thermometer, and we would have to do temperature checks every day in school. I don't know if they had had, like, you know, the touchless head, contactless head thermometers back then I would assume that would be easier than giving every kid an oral thermometer. But I didn't really understand the the seriousness of what was going on, because I was a child. And I just remember, like trying to get out of school trying to get out of class by rubbing my thermometer on my clothes so that it'd be really warm, putting my mouth and when my teacher would come and look at me. And look, I have a fever when I don't actually so, you know, as a child, I didn't understand or I didn't grasp the seriousness of of that. And my grandfather also worked in a place that was hit with an outbreak of SARS. So it was very serious. And he was thank God, he was fine. But you know, I just didn't understand that. And I remember, you know, we had a, I think my mom had booked a, like a year in advance, it was like some kind of performance that we're supposed to attend in a theater. And she was she wasn't sure if we should go because of what was happening or SARS, I think was this was in the early part, where it was still sort of, I guess, we weren't sure what the consequences of it were. And we did end up going to it. And all I remember of this was that it was packed. And I couldn't breathe through my mask. And I was washing on stage, but I couldn't focus. And I was really excited to be there. But I just couldn't breathe through the mask. And I was wondering what was going on. And it felt really hot and stuffy and claustrophobic in the room. And and then I think, you know, my mom and I to this day, I think she said she really regretted going to because you never know what could have happened with that many people. There and and there were a lot of sort of, like, I think when we lived there, there was a lot of sort of very community like solidarity against SARS, like everyone was wearing masks, there wasn't this sort of like push back. Now with the pandemic, where some people like refuse to wear a mask, or at least if there were I wasn't aware with it, about it, because of the mass sort of release of thermometers and, and information. And on the TV there were like celebrities, you know, doing like SARS related things, which I guess they did a little bit at the beginning of this pandemic too. But, so that's just my, what I remember of it, but again, I was very young. So a lot of that is, like sort of through what a child's lens

Kit Heintzman 07:49

to the extent that you're comfortable sharing what have been some of your interactions with health and healthcare, infrastructure, and what have those been like, pre in staying in the pre pandemic world.

Amanda Wong 08:01

Um, you know what, it is hard to get a family doctor, I think it is hard to find family doctors, that's one thing I've noticed. Another thing is it is hard to get access to mental health professionals. That is also another thing. Um, well, luckily, here in Canada, you know, it's healthcare. Some healthcare is free. They say healthcare is free, but some health care is free, some is not. And, you know, I, I remember when I moved here, when I was 12, I wasn't feeling well. And I said to my friend, and my friend was like, go see a doctor. And I was like, no, no, like, that's too much money, like, you know, it's fine. And my friend was like, you know, healthcare is free here. And I was like, 12, and I was like, Oh my God. Wow, what a what an idea. So like, you know, I guess going to see your family doctor is free, that's great. But what if you don't have a family doctor, you know, for a bit of time, when I had first moved to Toronto, I didn't have a family doctor. And so whenever I needed to see the doctor, I would go into this walking clinic and near me were the, you know, it was great that I had that access and was able to but I often met, you know, standing in line for a really long time and they also didn't really have a good track record of my medical history. So it would be re explaining and redoing tests all the time every time I went into this into this walk in and my health wasn't really very good at that time, mostly because I wasn't taking care of myself but also because I didn't I you know, and I also didn't have money to take care of myself anyways. So the the access was there, but the quality of of it was not ideal. I do now have a really great family doctor, and I can really notice the difference between having one and not having one. And the problem is so many people that I know are stuck in that state like me where we just couldn't find a family doctor. cuz no one was taking people or no one in the area was taking people or like, at the time, I don't know, it was it's hard to the the resources available to find a family doctor year aren't very blatantly visible for someone who doesn't, you know, want to go and dig. And then in terms of like mental health professionals like I, you know, it's not a most of like, if you want to go see a psychologist, a psychologist, a psychiatrist or a psychotherapist that's not covered by the government, it's usually covered by people's insurance, but what have you don't have insurance, you know, and I didn't have insurance for a long time when I was working freelance. And even if you do have insurance, you know, some people just don't really like the process is intimidating, because a lot of these places don't file it for you, you have to do it yourself. And then you have to go through, you know, agonizing sort of phone calls with insurance companies to try and get them to, to, to allow you to seek mental health, you know, and then even within, you know, sort of the infrastructures of mental health, I've certainly had really, really great therapists, and really, really great psychologists that have helped me.

Amanda Wong 11:16

Um, but before I found them, it was a process of the first time that I saw I was in university, and I was seeking help. And I went into I remember, I went into my university, the department that has the, you know, the school therapists and psychologists, and it took, like months to get an appointment, first of all, and then second of all, when I got there, they weren't really listening to me, the first thing that they asked was whether I was immediate harm of being suicidal, like, if I was not if, if I had it before, or if I think that I might, in theory, or if I am concerned, harming harming myself, they wouldn't even really concern about harm. It was, it was about a loss of life, like they were, they were asking if I was suicidal. And I said, No, not immediately or not. And they, and it was very sort of dismissive. And I never got a follow up appointment, because I wasn't on the priority, which I understand, you know, you got to give priority to the people who need it. But why is it? Aren't there the resources available for people to access before they get to that point, right? Because this is how you know, you, if you're, why are we only solving things when it gets to the, you know, the intense point before a while, where there are people who are coming to seek help, so that they don't get to that point, and you're turning them away. So that was my first experience with that. And I was, like, I hate the mental health structures, and I, and I'm never going to go through this again, like it was really degrading. And, and then so many years later, you know, I was, I decided to try again, to keep an open mind. And, you know, someone told me that, you know, sometimes you have to do a little bit of shopping, quote unquote, shopping for and luckily, I was able to find somebody, but you know, not everyone is able to shop, whether it's time or money or like it's so it feels inaccessible. And I wish that there were a better sort of accessible infrastructure, and also institutions, and also professionals who are working within that, that framework that not everyone can afford to pay $250 for a half hour interview, you know, and, and luckily, my first therapist was working on a sliding scale. And, and, and she worked with people who couldn't afford these large amounts of money. And she worked at an institute that, um, you know, you could work with people who were in like, third or fourth year, like they hadn't yet graduated, but then you could work on a subsidized sort of sliding scale. And that was amazing when I found that that was like, the change that really helped me, you know, get better, and I really needed to get better. So I was really lucky in that way. But you know, not everyone else is that lucky, and I see a lot of people who struggle with accessing, you know, resources because they had a bad experience, or because they are just unable to find anything or find anyone who will help them. So, you know, I feel very privileged in that way, but how can we I wish that it could be better for people who, who didn't have a happy ending like I did you know what I mean? So.

Kit Heintzman 14:52

Staying in the pre pandemic times, would you say a little bit about what your day to day was looking like before COVID-19 really hit and started to shake up our world.

Amanda Wong 15:04

Um, well, right before the pandemic, I was working freelance as a in the film industry. And at the same time, we were also as part of the band kutsu, we were also playing shows and, you know, doing live shows and putting out music. And we were recording our first debut EP, and which actually like in the middle, we we recorded it all, basically the month before the lockdown hit. And by the time we got into the mixing stage, that was when we were locked down. And so we would have to be Luckily, our amazing producer, you know, was able to set up a system that allowed us to mix online with him, like, you know, sit sit in his mix online as he was mixing. So, it, I was, I was definitely, you know, moving around a lot, I moved around the city a lot for work, also for music. But, you know, I was also very social person, you know, I would spend most of my evenings with friends with my partner, or dress going about the city, to events and shows and films and things. And I live right downtown. So it is quite busy. And, you know, I think that we didn't realize when the pandemic hit what a change it was going to be. But yeah, so definitely, I guess my day to day was quite busy, quite filled with activity, and quite filled with social activity.

Kit Heintzman 16:48

Like you remember about when COVID-19 first hit your radar when you first started to notice it, and how were your reactions developing over time.

Amanda Wong 17:00

Right, right. So it's hard to remember to be very honest, it's hard to remember exactly what it was like, because I think that it happens almost overnight, while at the same time. So glacially that it's like this weird thing to pinpoint. But I remember that, because I was working on a number of sets of film sets at the time that these film sets were, you know, sort of on edge because they're waiting to hear what the latest news was that we would be allowed to film or not allowed to film. And I think in Toronto here, the lockdown hit when we were in March of 2020. And I remember, we were on a set, and I was not feeling well. And I was like this. This can't be COVID Actually, actually Leanne, who was in my band, who's in my band, we were at a meeting where she was saying, and I'm pretty sure that I got sick from her. I'm sorry, Leanne, if you're reading this. But, um, who knows where I got sick from but you know, she was, I feel like we were in a closed room at that time. And so I was sick, and which is fine, you know, people get sick, that's normal. But when, because of all the anxiety of the pandemic and stuff, you know, it just starts to make you think like, Oh, my God, do I have COVID I'm pretty sure I didn't, I had a flu. But um, and then I was at work, I was on set, and I was still sick. It was like this. I was sick. And then I was well and I was sick. And then I was on set and I wasn't feeling very well. And I remember the next day I was supposed to go visit my parents because it was my birthday. And they live out of town. And so I went there and I was like, Okay, I'm not really sick because I literally just got well from being sick again. So I'm just gonna like, you know, take, take some meds, take some like, you know, NyQuil or something, go to bed, and I'll be fine the next morning. And then I woke up on my birthday feeling really sick. And then my parents were really worried. And so we cancelled everything that we were supposed to do, like, my brother was supposed to come in from out of town to and it was like, Okay, we're canceling everything because we can't, this is not safe. And then I got an Uber back to back to back home. And I remember being so sick that I climbed into my room and the first thing I did was throw up and then I slept. So that was my birthday. And then the lockdown basically was announced a couple of days after that. And for a while I thought like did I have COVID and I was worried that I had, you know, maybe not knowing it, I would inadvertently spread it to other people. You know now knowing what we know about COVID You know The symptoms and things like that. I didn't, I'm pretty sure I didn't have COVID. But also the testing wasn't available then either. So how How would I know? But everyone around me was fine. You know, the people that I was on set with, I was constantly sanitizing my hands, and I checked involve them, and none of them got sick. So thank goodness. And, but it was like that fear of like, we don't know what's going to happen. So maybe if I'm sick that does that mean, I have COVID, you know, anybody could have COVID. And then I was so scared to go outside because I thought maybe, you know, like, I didn't want to kill anybody. And I had friends who were you know, older there, I have friends who were you know, in their 60s, and they wanted to go out for, for a walk, and I was like, I really don't want to kill you. And I was like, I have been staying at home. But I don't want to accidentally, you know, who knows what, because we didn't know anything about the virus at the time, we didn't know anything about COVID-19 or how it spread, now we have information, and we still don't really know. But back then it was so scary because of how pervasive it was, but also how invisible it was, and how quickly it affected people. And I never wanted to be in a position where I would accidentally affect somebody. So I stayed inside a lot I was, you know, I think we were also really lucky here in Canada to have that, you know, funding sort of kick in, you know, where there's, like a sort of emergency response, like benefits that kicked in that we were able to sort of, you know, if we don't have work or we get lost work, we were able to still, you know, stay inside and, and get some get a little bit of benefits from the government to, to stay alive and pay rents.

Amanda Wong 21:46

Um, but so that's how I remember a lot of it going down and happening so quickly, while also like we knew about it, we knew it was coming, and just sort of like the fear surrounding that. And you know, my partner had just come back from Asia too. And it was, oh, and I was actually now I remember, I was supposed to go to Asia to I had, I had a plane ticket and a visa already. I had already gotten my visa. And I had already had a plane ticket to go see my grandma, and in Asia, and we had to cancel that because of because of, you know, COVID And I think that we already can't start canceling that in February because we kind of knew that it was coming. So So yeah, there was a lot of sort of a guessing guesswork. Trying to be preemptively careful. And, you know, with what we had, I guess that's how I remember it. And just trying to stay as vigilant as we could without, you know, falling too far in to interfere or, you know, conjecture, unscientific conjecture anyway. Uh, definitely, a lot of people were arguing with each other about, about the, about the pandemic, you know, some people still believed it was a hoax. And yeah.

Kit Heintzman 23:24

I'd like to follow up. You had mentioned that your partner was returning? What's the partnership been? Like, during the pandemic for you?

Amanda Wong 23:36

Um, yeah, I mean, that's an interesting question. So I don't live with my partner. So that's another thing that when the pandemic hit, we definitely saw each other a lot less, because we were trying to be safe. And we were trying to see each other once a week kind of thing. But then that might get moved, depending on you know, we both also live with roommates. So if one of our roommates isn't feeling well, or if one of our roommates was going off to work somewhere that might be slightly risky, then we would have to cancel our meaning for that day. You know, so, but I think I was very, we're very lucky in that the fact that we both worked in the film industry, and there was a good chunk of time there where the film industry had nothing going on. There was just no work so so we were able to see each other for more than once a week. But within the confines of our own spaces, like we wouldn't, we wouldn't be able to go out and do anything, of course, but we were kind of in the same bubble. We kept our same bubble. And then sort of when things started opening up, and when, you know, we started booking more work, and then that became a little bit more complicated to organize because, you know, we also have to respect our rules. meets safeties as well. And then, and vice versa. So, um, so now we kind of just, you know, we try to, we try to see each other once a week, within the, you know, the confines of our own places, and, like, depending on, you know, who's feeling well, and, or not, and just sort of always running it by our roommates to have like, this is okay, that this person comes over, you know, so

Kit Heintzman 25:29

what are some of the ways that you've had to adapt your day to day living from pre pandemic to mid pandemic?

Amanda Wong 25:40

Yeah, um, you know, what, I have never enjoyed my home, pre, like, I've never enjoyed my home the way that like, I have, after the pandemic, like, and when I say enjoy, I mean, like, also just, like, appreciating that I have the home, you know, the, like, obviously, I had lived in my, my apartment for how long had I lived here before the pandemic, like two years, but I was always working. So like, it was only just the place that I came back here to sleep, right? Like, I didn't really do things here, because I worked and then I came home. And, you know, being now being forced to sort of stay inside, I have now sort of been able to take the time to look at my space, better, you know, it's not just a place for me to sleep. You know, there are better ways that I can do better things I can do to make this place better for me too, now that I have to be here for 24 hours, you know, a better sort of a better computer stand. So I'm not like craning my neck like this, when I'm like, you know, some decorations maybes with the wall aren't so isn't so bare, you know, what, what are the ways that I could do to make the space better, but then also just I find myself just like, sitting down sometimes, or just lying down, and like looking at my space around me and being so thankful for the fact that I have this space, you know, like, I have the space to like, call my own, I have the space that I have the autonomy to change and do whatever I want to to this space, I mean, within rental limits, obviously. But you know, it's not something that I necessarily like took the time to think about before the fact that I have a space. That was that was a space that I could call mine. So I think that was like the biggest difference between pre pandemic and after was that, that I just became more aware of my space and how lucky I was.

Kit Heintzman 28:04

So COVID has only been one of many political, social, natural environmental issues of 2020 to present. And I'm wondering what some of the within that within that context was some of the big issues have been on your mind over the last year and some change?

Amanda Wong 28:29

I'm sorry, do you mind just repeating that question again?

Kit Heintzman 28:34

No, not at all. The shorter the shorter, clearer version? Maybe is? What are some of the big political, social or environmental natural issues that have been on your mind? 2020? To present?

Amanda Wong 28:52

Right? Well, first of all, I've been really aware of how the pandemic has affected different groups of people within the city that I live in, I can't speak to other places, but within Toronto, it is the, you know, the neighborhoods where people are, you know, have to, they don't have the luxury to stay at home because they have to work. They have to work jobs where they, you know, they have to be there, you know, like, whether they're service jobs or, you know, like technician jobs, or, or whatever it is like that those neighborhoods are disproportionately affected, right. And often that these these neighborhoods are our neighborhoods where they're the high immigrant rate or, like, a larger demographic of people of color. Because of the ways that I know that the people of color are disproportionately affected even just in if you're not thinking of pandemic in terms of the economic or social level, right. And then you add the pandemic onto that like these numbers. hoods are, are, are just at a disadvantage when it comes to being able to take care of yourself because you can't because you need to live because you need to work. And, or, or neighborhoods where, you know, people don't have access to space, whether the fact is that, you know, they're a larger family living in a smaller space, or maybe they don't have a space at all right, like a lot of people have lost their homes during the pandemic. And I've seen, you know, in, in my neighborhood alone, I've seen, you know, tents and and many sort of makeshift places that have have that spaces that people have made it for themselves, and how do you protect yourself in that kind of circumstance are this is this is just this is the one of one of the aspects of the sort of inequalities that have come to that I've come to see that, you know, that the people who are able to stay indoors and are you know, have more money, are still taking vacations to you know, they're still flying around and taking vacations. And, you know, they know that they'll be fine, because they have access, they have access and the resources to go and get tested or, you know, or being safe or whatever, but, like, safe, but, um, you know, I I realized this transcribe tester, I should say, as it's safe, quote, unquote. And whereas like, you know, we don't think about the resources that impact, even getting to those resources, for example, like, you know, if you don't have a car, like, how do you even go and get to the testing center, you have to walk right, like my roommates, one of my roommates, friends, when he was told that he might have, he might have come into contact with COVID had to go to a testing center, but the nearest one that he could go to, or that was open at the time was like, an hour away from his hour walk away from his home, if you drove there, you can get there in 10 minutes, walking there. So he walked to the clinic, there and back, and it was like an hour there an hour back. And actually, it might have been more than an hour might have been like three hours or something. Anyways, it was really far away. And I don't want to say it was an hour because it might have been more than that. And this is also not, I'm not clear on the details anyway. So he had to walk really far away. And then he was he was he tested positive for COVID. So like, you know, it's like these kinds of things. It's like, why are there no resources for people to get tested closer to where they are, like, this poor man who hat was who, who had COVID in order to take care of other people and make sure that he didn't affect other people had to walk like ours to a testing center. Um, you know, just stuff like that other people maybe don't, I don't know, like that, that isn't necessarily. Like, anyway, I'm just using this example. This very big example with no names or details to just add to, to explain like how, you know, even even that, people who you don't have, if you don't have a car, you just you're, you know, you're affected in ways that other people who have cars do have that, you know, ability to, to have access to things.

Amanda Wong 33:25

So, that's a huge thing that I've been thinking about. I mean, also, there have been, I mean, I try not to think about this too much, because I think it is a little bit is traumatic for, I think, a lot of Asian diasporic people to think about, but like the anti Asian racism that has sort of been like increasing during the time, you know, people talking about the virus, like it's, you know, the Chinese virus, or, you know, the, the Wuhan virus or something like that, like, where they specifically tie it to a sort of ethnicity or place, you know, and it's, or, you know, the ways that I've heard stories of people who, you know, they're, they don't want to go into a store where, you know, they, there's Asian people there because they're afraid that they're going to carry the virus somehow, even though, you know, because a lot of the people a lot of are talking about this to someone else, a lot of a lot of people, a lot of Asian folks who have gone through the experience of SARS are actually more careful, because they have gone through and they know what it's like to be in. That kind of, I don't know what SARS was, was in an epidemic, I don't know, to be in that sort of environment, whatever, whatever it was called. So I think that that's, that's an issue that has been on my mind too. And I think that You know, with, with everything that has sort of I don't, this is not pandemic related, because this is something that has been going on for a while. And it just kind of came to a point. And 2020 is obviously, you know, the way that black and indigenous communities are treated by the government, by society, just, you know, that inequalities that are that are just systematic there, right. And, obviously, this is not pandemic related, this has been happening for a long time, and it's still happening. But I think that when people were forced to actually take a look around them, when they had some time to take a look of what the heck was going on around them, during the pandemic, that these, these issues that had always been there had just became more people just became more aware to what they were maybe blinded to before. So I, I think that these are important ongoing issues that we need to talk to continue talking about even past the pandemic. And like everything that I had said earlier, about, you know, access and, you know, racism, and to say that these are not just pandemic related things, but maybe that they came about because people became more aware. And I say people generally, I don't mean all people, certainly there are people who are more aware. But I think the amount of people who were putting in the work to bait to to look around them has increased from before. So, I Yeah, where am I going with this? I think that was, I think that those are the issues that are on my mind, I can certainly go on and on and on about issues and concerns. But I think I'll leave it there.

Kit Heintzman 37:12

And curious, what does health mean to you?

Amanda Wong 37:15

Yeah. Mmm hmm. I think that in the Western world, that there is sort of this idea that health care happens when you're sick. You know, like, when you're sick, you go see a doctor. And not I'm not to say that all of the systems within you know, sort of health care like this, you there are lots of others that aren't, for example, naturopaths, or, you know, chiropractors or, you know, like your even your annual Doctor checkups, like you go in and do them when you're not sick, right. But I think that there's this idea where you only fix yourself, if you are sick, you know, where, whereas I think that there needs to be maybe more of an understanding that health is like an ongoing thing, that even when you're not sick, that you should be able to take care of yourself so that you don't get to the point where you're sick, and then you can't do anything. And I think that a lot of this has this, like, you know, this tendency of us to look at life as like bare life, you know, like, like, the necessities of life, like, Oh, if you are alive, then you're fine. Right? Like, and then you don't really look at people, or maybe not like, not like us living people, but maybe the way that like, the sort of government and the state sees people right, like, will keep them alive. But only like, you know, when they're when they're sick, they'll see a doctor, but the systems that, you know, keep them alive to have a good and healthy life are not exactly there. Right. So like, for example, sure, yeah, the government covers health care for people to go and get checkups. When they're sick, you know, they can go and if they have a problem, they can go and see their doctor, they can go get screened for like X rays or ultrasounds or whatever to check on that thing. That you know, isn't feeling so well. But other systems like you know, dental or vision, or mental health, or like, you know, natural pathI or Eastern medicine, like all these other things that maybe prioritize and ongoing health, you know, are not things that are covered by the government because they're not because the government sees people as sort of like the spare life like you need where you can to survive, right? But health to me, I think is important to take into consideration that is an ongoing thing and in order for people to not you know, wait till the last minute until you're sick to go see a doctor health involves, you know, an ongoing access to be able to take care of yourself, whether it is you know, dental or vision or anything or you know, or chiropractic or anything else that, you know, facilitates like a good health depending it depends on the person obviously. And so I think that that health for me is, and it's like an ongoing wellness that people may want to have, but may not be able to access. And we can do the best that we can to access and make healthy choices. But for the larger part, you know, when when someone tells you to, like make healthy choices, they're not asking you, are you even able to make those choices, right? Like someone can say, oh, you should, you know, be healthier and eat organic food? Well, we know that organic food is like twice the amount of non organic food. So if someone isn't, you know, financially able to afford that health, you know, what, what does that mean? Like? How do we How to, there are so many levels of like, what health is I think and, and, and even though health is ongoing, it's it's all about access to but about remembering what access people have and what and what they don't? So

Kit Heintzman 41:35

What are some of the things that you want for your own health and the health of people around you, and what you think would have to change in order to make that possible?

Amanda Wong 41:45

Right, I think I touched on this a little bit in my previous answer that I would love for access to be able to be better, I don't know, more, it's more, I would like it to be more accessible for people to find resources, first of all, on how to even you know, improve their health, or check in on the check in on themselves. And like we said earlier, remembering that they have a body. Um, and I think that, you know, our, maybe it is just like the way that our society is built sometimes on this, like very, on this model of like productivity, right, that people are seen as in terms of the amount of that they can output. But I would like there for there to be a sort of like a shift, maybe like a little paradigm shift to sort of see things people as not things or not as producers or, or users or QA modifiable, like, you know, like, outside of these terms, and to be able to make health a priority, so that they don't have to, you know, work a second job just so that they can afford health care. And for healthcare to be more inclusive, and the what it defines as healthcare, you know, I've heard a lot of struggles of people who are trying to seek a certain health care that may not be respected by their insurance. And I just want to, I think that we should maybe be more inclusive and the things that people need, because everybody's body is different, you know, some people might respond to this, and some people might respond to other things. And, you know, I've heard a lot of people say that, you know, Eastern medicine is not medicine. But, you know, I grew up with Eastern medicine, and I can tell you that it works for me, and maybe somebody else, you know, it doesn't work for them. And that's okay, like they don't have to do it. But for the people who does work for like, it's not, it's not seen as something that is legitimate, or you know, like healthcare is a little bit exclusive in the way that they sort of define things. But I think all forms of wellness can be healthcare, right with their people can argue whether it's scientific or not, that's another conversation. That's a separate conversation. The conversation I want to have is about access and access to wellness and that how health should be surrounded to shit like should be thought of in those terms is access to wellness. And your question about how do we do that? I to be honest, I don't know how, how, if there wasn't easy answer probably it would have been done already. Or maybe not, who knows. But I think, on our level on a level where we're not necessarily making, you know, big decisions about infrastructure or policies on our level, just talking about being more open to talk about health with your peers in a non judgmental way, you know, like, don't be like, Oh, be healthier, you know, but just talking about your, like, being more open to share your own health journey with other people. So that we can all understand, you know, what, what the resources are, we could share resources with each other, you know, because if I say, Oh, hey, I had some trouble with accessing a therapist, and someone else was like, Oh, I had trouble too. Just because by way of sharing, now, I can share the resources that I had with them. Right. So I think there is a lot of stigma about talking about health. And sorry, I'm just going to turn off my notifications that are ringing here. There is a lot of stigma around talking about health, that people you know, don't want to necessarily disclose. And that's okay. You know, you don't have something that you don't want to disclose, you don't have to but I think, in a general like community sense.

Amanda Wong 46:17

If there is something that you're comfortable about, about sharing, but you're not sure if somebody else wants to hear, I think that the more that we can share resources and these things with each other, the more we talk about it, then the more able we are to understand what the barriers are for each other of accessing these things, and then allowing us to help each other with that. That's on like, what I feel like I could do at my, you know, level, but you know, I hope that the people who are making decisions at high at a higher level and like sort of policy or infrastructure level, are thinking about these things. And I and I'm sure they are. But it's until I see them happening. It's hard to determine whether they are happening, and maybe they are slowly. Thing, everything moves slowly. So I think patients too, I'm trying to be patient, trying to not try to understand where they're coming from, too. You know, it's not you can't just build a hospital in a day, right. They're also limited by the budget and the funds that they have. But I think as long as we're moving forward, and we're thinking about these things, and we're talking about these things, that that is a good direction to move in.

Kit Heintzman 47:37

What does safety mean to you?

Amanda Wong 47:40

Safety? Good question. That's a good question. I don't really know how to answer. Um,

Amanda Wong 48:02

I want to say I want to say that safety is when you don't, when you don't have that feeling of like that fight or flight feeling that feeling of anxiety or that feeling of fear that you're in a position that you're not in control of. But I don't want to define safety by what it not what it isn't, you know, and I'm trying to think about what safety means of what it is. And I think it it often involves a sense of security, and involves a sense of consent. And, and it involves a sense of autonomy and control over one's own decisions space. And yeah, I think that's what it means to be in. So this can be applied in many different ways, obviously, physical safety and, you know, safety within like social safety, like safety within, you know, social situations and also safety in terms of prevention of harm, I think is important. When we think of safety often, safety, for some reason, often goes hand in hand with like danger, like when we think about danger, we think about safety and that isn't when right where we think about safety, defining is what it isn't, which is danger and so, we only think of safety when danger is present and how to prevent danger, but safety is not just a prevention of of that safety is you know, it is yes, it is prevention, but it is also there is also an element of like we should be enforcing safety even it All spaces, you know, not just spaces that have danger. You know, like, so something specific to like, our band is, you know, we are always making sure that the shows that we play are safe, whether that means, you know, making sure that there are gender neutral washrooms that are available or at the beginning of the show checking in to see how is everybody doing today? Or laying down some, or like, you know, checking in after, you know, someone has, like, jumped off the stage or something is everyone okay, they're, you know, like, everyone make sure. Or it's just like, you know, make sure that you're, like, just checking in, you know, they're not necessarily that there is any danger, imminent in that scenario. But you know, some people, some people, some people don't feel don't even feel safe when there isn't danger around, right. And so it's just checking in with that. I feel like we live in a world where danger isn't so implicit or sorry, explicitly outlined, right, what is dangerous to one person is not dangerous to another and vice versa. So safety is also checking in on people's boundaries, and what makes them feel unsafe. You know, even if we think that there is no danger here, maybe there is for this person. So, I think that this is a very long about answer of me meandering around what safety means. But hey, we started for me not knowing how to answer this question. And I've kind of just just kind of just walk my thoughts out. And I wonder how someone's going to transcribe blah. But here we are.

Kit Heintzman 51:47

I want to take a second and affirm that there is no sort of like trailing off or rambling or anything in an oral history interview, like, by definition, everything you have to say, is as valuable and a gift that you're giving me and whoever ends up listening.

Amanda Wong 52:06

Yeah,

Kit Heintzman 52:07

So thank you for that answer. And no, no judgment about how one gets to their answer along the way.

Amanda Wong 52:19

Thank you for, uh, for making me feel [inaudible].

Kit Heintzman 52:24

So there's been this really narrow conversation of safety under COVID-19. That's very much attached to idea of viruses and bodily interactions. And I'm wondering at sort of that microscopic scale, how you've been negotiating how you've been determining what feels safe for you, and how you've been negotiating that with others?

Amanda Wong 52:46

Yeah, for sure. Like, I think safety is one of those big things that during the pandemic has split apart, friendships, split apart, partnerships, split apart roommates, family members, because there is a misalignment of what each person defines as safe. And I think that what is key within all of these scenarios is communication. Right? Like this, you know, I mentioned that I mentioned earlier that when I have my partner over, or if my roommate has their partner over, like, we try to keep in communication about what that means for each of us. And we try to be considerate of others, you know, because what is safe for one person might not be safer for others. And I think that as long as we keep open communication, transparency and like a consideration for others, then these forms of what people define as safe, or safety can be negotiated. and respected. You know, like, I have the word negotiate. It sounds weird, because it almost sounds like you're coming to some kind of like, bargain transaction. But I but what I really mean is respect respected, you know, like, if someone says, If someone says, you know, I don't feel comfortable with, you know, you going to that job, I'm not going to be like, No, let's meet halfway, because you're because the, it's not a negotiation is more of like a What can I do to make sure that I abide by that, you know, like, what, so maybe, after I do the job, like, I will go get tested or after I go do the job, maybe for that day, I'll see if I can stay with a friend, you know, for that period of time, or, you know, ways that's where the negotiation is, right? It's like how to make that happen, how to make that work for both yourself and the person who was telling you about their safety than it association is not let me meet you halfway, because then you're not respecting anybody's safety. And, you know, I had some trouble with that at the beginning of the pandemic, because, you know, people have jobs, and people have lives, and people need to go to work, and they need to survive, and my roommate works a service job. So, for me, it's also understanding that, you know, sometimes my safety needs can't be met, all the way. So it's a double, right. It's also the person who is asking for more ability to and also the person is asking for safety, the person asking for safety, aka me, I also have to remember that, you know, she doesn't have necessarily have the privilege that I do to work from home. So what does that mean for us? You know, I can't tell her to not go to work. I can't tell her to not see her partner, because that for her, that's an emotional support, I would be removing her emotional support. If I said, No, you can't, you can't see your partner, because I don't feel safe. So it's just finding ways about how to, to make that work. So whether that means like, you know, when your partner comes over, I'll stay in my room, you know, or when you go to work, like, make sure that you're using full PPE and social distancing. And I trust you. And it's the, it's the same, the same back and forth to we've definitely had issues where, you know, my roommates, previous partner was traveling. And that became an issue of, okay, well, I will go and stay at my friend's place for two weeks. And then the next time that that happened, it was her saying, Okay, we will go and stay at a place for two weeks so that we're not, you know, bothering you. And it just depends on our work schedules too. So I think that's where the negotiation happens. It's not that, you know, you're trying to change somebody's mind about safety, you're trying to make it work for both parties. And unfortunately, that doesn't happen, that can't happen all the time, because of limitations, resources. And, unfortunately, that does split people up. And I can only hope that in the event of those things, like maybe after the pandemic, that these sort of relationships resolved. I don't know, I feel bad for people in those circumstances.

Amanda Wong 57:35

And I'm very lucky that I, you know, I haven't necessarily had too too terrible of an experience with negotiate negotiating safety. But you know, I work on, I work on a film set, like safety is so important in terms of like, PPE, and like making sure that you're protected, and thermometers and protocols and things like that. It's very methodical, and I'm glad that we have these methods and these policies in place, but to also remember, the larger reason about why we have these policies in place is to protect people and their safety not to, you know, just follow some rules. And that's the Beyond and all like, it involves negotiation, and involves caring, involves communication involves transparency. And I think that I try to keep for my myself personally, anyway, I try to remember these things when I am talking to someone about safety and COVID.

Kit Heintzman 58:34

How are you feeling about the immediate future?

Amanda Wong 58:41

I think that now that more people have gotten their vaccines, we're slowly slowly getting vaccinated. We've slowly sort of accustomed to the pressures of working under a pandemic. I think there's also an increased awareness and, you know, education that's sort of been happening around health and, you know, wash your hands and like wear a mask when you're sick. And that wasn't necessarily something prevailing in North America, and most of North America Anyways, before, I think that I have a positive outlook of the future. I think that there are definitely ways that our society has changed for the better, there are also ways that it has not changed for the better and if anything, has become worse. But it's I think I'm a generally optimistic person. And I feel like the amount of support and solidarity that the community has for each other during such a time such an intense time only means that when we're out of this intense time, that that that that we will be okay, you know, so I and I don't know When the pandemic is going to end, and I don't hope to presume that it ends soon. And to be honest, I'm okay, if it doesn't, because I think that people need to be safe first before we can go back to normal, quote unquote, because the what is what the normal even mean, before that, right, there are definitely things that were normal, quote unquote, then that are that during the pandemic, we realized that those were not normal, those were harmful. Those were harmful habits, you know, why do people have to, you know, stay at work for over hours when they could finish their work within three hours? And why do people have to go in to do this, when it could have been done remotely? Where it would be more safe? And why are there no, not that many systems of like, child care, for example, for people during, and this is, these are all things that came up during the pandemic? And, you know, why do these sort of viruses and these health issues disproportionately, in fact, impact certain neighborhoods more than others, or certain groups of people more than others, and I think all of these things were, you know, are awful that it happens in the pandemic, but we should be looking at these things moving forward, as to how we can make them not, quote unquote, normal as they were seeing before, you know, so that's why I'm, I'm staying positive to the future of what I think that the future will hold with the pandemic. And I think with everything that, you know, it's, nothing is a utopia, nothing is utopic, it will not be perfect. But we can try at our level at whatever level we're at, in our, you know, our groups and spaces.

Kit Heintzman 1:02:04

So self care has been a really powerful part of the 2020-2021 narrative. And I'm wondering, if self care has been something you've been able to practice what that's looked like for you.

Amanda Wong 1:02:19

Right, um, I think my first sort of knowledge of self care came when I started to take care of my mental health when I started to seek help for my mental health, and that was my first sort of understanding of what self care means. And then certainly, as you said, during the pandemic, there has been like a wider awareness of what self care means. And I think that that, you know, involves a lot of mindfulness and boundary setting. And sorry, were you asking me what self care is? Or how do I see self care and the pandemic?

Kit Heintzman 1:03:06

If you've been able to practice self care

Amanda Wong 1:03:09

Oh if I

Kit Heintzman 1:03:09

and what thats looked like? Yeah.

Amanda Wong 1:03:12

Um, I tried to, I certainly tried to, um, but if I'm being very honest, I don't succeed most of the time. And I think maybe this is a very big assumption, but I think that a lot of people do have trouble practicing self care, because we live in a culture that always sort of expects an output from people, right, like, we're expected to have an output. And if we're not having an output, then we're seen as, you know, not, I don't know, their, you know, their words that are thrown out at people who might not be able to output like lazy or, you know, like they're there. They're not hard working, or something where this is not really the case. Like, we cannot judge people by their output. And also, this doesn't take into account you know, disabilities and neuro divergence and other things that might affect people's ability to output. And so I think that because of that, not a lot of people are very, like, I feel like a lot of people even though we try to practice self care, if there's a guilt in practicing self care, you know, in that in taking care of ourselves, like there's a guilt because we're not outputting. And that's not the case for everyone. For some people, their self care might be off putting, but for me personally, my self care means taking a step back from outputting and reminding myself that I'm not a machine and that you know, the boundaries need to be set and that it is okay to say what you want and what you need from others. People, you're not always obligated to give people what they want, or need. And you are allowed to say what you want, and you need. And even then I struggle with it. You know, like, I feel bad even asking, Can I go to the bathroom? Can I pause this and go to the bathroom? You know, luckily, I haven't needed to yet but but you know, it's just like, it's just like things like that, like you try to, but then you forget, because because of how, you know, we're sort of sort of like the culture we're in, I guess, I don't know, I don't know what it is. I don't know what they I don't know the answers to anything. I don't know what I'm saying. But that's, that's how that's my own experience with anyone I try to, but it is tough.

Kit Heintzman 1:05:50

This is my second last question. And it's a little odd. Um, so we know that there's all of this scientific and medical research happening right now, because there has to be. But I'm wondering what you think people in the humanities and the social sciences can be doing to help us understand this moment.

Amanda Wong 1:06:15

I think what we're doing now is great. I think that, um, I think the oral histories are important, I think hearing from individuals are important. Everyone has a different perspective experiences. And I think sometimes we can get inundated by facts and numbers. And, you know, in the future, when people look back into the documentations, or the work that was produced in the pandemic, I hope that they are able to see beyond like the numbers of people that died, or the numbers of people that got their vaccine, and they can be able to understand the individual experiences of the people living in the pandemic. And I think that if the humanities or social science, like work that is being conducted on the pandemic, keeps that individuality and perspective in mind. When doing their work, then that seems like a good place to start. And so I'm very glad to be doing this.

Kit Heintzman 1:07:27

This is my last question. And you may feel like it was encompassed in the last answer, and if so, just say so. So this is an oral history interview. And I'd like to invite you to imagine a historian of the future one who never lived through this moment. So one for whom someone who has zero experiential knowledge of now, what are some of the stories you would tell that historian, it's really important that they not be forgotten?

Amanda Wong 1:08:02

Hmm. Hmm. That's a good question. I don't know how to think about that one. Um, I think a number of the issues that I brought up earlier, are probably important to note beyond a, like, vague overview that I gave, you know, like, talking to actual people have been impacted by the issues. And why hope that a historian in the future would be able to access these stories. That's the question, right, that what are the historian we'll find these things? Yeah. And I think that, also what I said in the last question about individualized experiences, and experiences beyond the, like, mass majority, you know, like experiences of the minority, and experiences of from, like, diverse perspectives. And I think also, the ways in which the pandemic affects different groups of people is important to remember to recognize and to not pass judgment on. Right, like, you know, everybody has reasons why they do things. And if we don't hear those voices, then we don't know what those reasons are. And then these assumptions can be made by historians in the future, which so I think that it's important to get those those voices to be able to speak for themselves and not under like, judgment or assumption. And I don't know like I'm everyone as guilty of it, I'm sure I've made a number of assumptions or judgments in this whole in this whole interview, but whatever we can, I guess. And I think that is important to recognize the global nature of how we've been affected by the pandemic. And how different areas have been impacted differently to have right i i, you know, like some places had first, second, third, fourth waves, and some places only had a first wave. What else about the pandemic? Would be is sort of what what was the question? What else in the pandemic should the historian remember? Hey, got that pretty much covers it on an overall basis. Oh, I think it's important to not focus on the negative stuff, too. Like, there is a lot of negative stuff, and it's easy to rant about. And about, and I did, I just did the same about, you know, all the things that should be better and, but are not. And it's important to talk about for sure, like, we need to know the negative in order to address it. But I think we should also remember the positives that came out of it, like, the support, that, that came from the solidarity, the amount of work that organizations did put in to help people in their neighborhood, to help impacted groups. And, or the ways that, you know, people who may not necessarily have anything in common have, like, come to help each other too. And, I, I think that there's also like, a weird, like, not weird, but like, a, an interesting, I was talking to somebody about this interesting group of the new generation that grew up in the pandemic, and how that's going to impact them, you know, like, a friend of mine, like had a kid basically, at the beginning of the pandemic, who's like to know, and I'm like, basically, this kid's entire life has been indoors, and how does this impact our next generation? And will there be, you know, sort of lost, things lost in translation between are, like, there are already things that are lost in translation between generations, whatever generations means, you know, people of different ages or experiences, but let it let alone like, you know, a whole group of people that have grown up in the pandemic, and I think that there will be stuff lost in translation. And if a historian is looking back at this, like, way, way, in the future, I'm assuming that they might be. They might be someone who was born in the pandemic grew up in the penet post pandemic, and I, I'm glad that you're asking me pre pandemic questions, because for that historian, maybe they never lived in a world where the pandemic was pre it was always the, the pandemic, you know, um, so, I think kind of remembering that difference in perspective, too, and the loss of like, perspective or translation that might happen through that.

Kit Heintzman 1:13:25

I want to thank you so much for everything that you share. That is it for my questions, but at this point, I just want to open up some space if there's something that you'd like to say that my questions haven't provided that space for here this

Amanda Wong 1:13:42

I don't think I have anything else I think I'm just very thankful to be a part of this. And like, Thank you for inviting me to do this interview. And I guess for anyone who was reading this in the future, thank you for reading and watching this and I wish you all the bests on whatever works you're watching thisfor.

Kit Heintzman 1:14:07

Thank you

Hello

Amanda Wong 00:01

Hello.

Kit Heintzman 00:04

Would you please start by telling me your full name, the date, the time and your location?

Amanda Wong 00:09

Yeah, my name is Amanda long. The date today is May 12, 2021. And I am located in Toronto, Ontario.

Kit Heintzman 00:21

And did you say the time or did I miss it?

Amanda Wong 00:24

I didn't, because I'm totally missed it. My lack of focus my ADHD. It's Wednesday, the 1:48pm. Right now, currently.

Kit Heintzman 00:38

And do you consent to having this interview recorded, digitally uploaded and publicly released under Creative Commons License attribution noncommercial sharealike?

Amanda Wong 00:49

Yes.

Kit Heintzman 00:50

Thank you. I'd like to just start by asking you to introduce yourself to anyone who might find themselves listening to this what would you want them to know about you and the context you're speaking from?

Amanda Wong 01:02

Yeah, so my name is Amanda Wong, and I am a member of the band cut sleeve. We are an all queer, East Asian art rock band based here in Toronto. And I on the side, I am also a filmmaker and sound artist and I am an immigrant here to Canada. I moved here when I was 12. And I guess that's it. I'm trying to think about any other interesting or things that would pertain to this, but I think we'll go with that for now.

Kit Heintzman 01:44

What do you what just the word pandemic, conjuring you when you hear it?

Amanda Wong 01:51

The word pandemic we talking about now, or pre COVID?

Kit Heintzman 01:58

Oh, I'd love to hear about both.

Amanda Wong 02:00

Um, I think before COVID I, I didn't really think much about the word out to be honest, I would not be able to know the difference between epidemic or pandemic or the other dynamics or, and I do know that there is a board game called pandemic. And I you know, I, I lived in Asia during the time of SARS. So, I also have experience with that. So, I would probably think about SARS. Although, you know, it was not anywhere near the level of what this is the you know, COVID-19 is now and then after sort of COVID-19 started taking over the world. I when I hear pandemic I think about the all the other associations that come along with it the lockdown the staying at home, the numbers of people that have died from anti vaxxers people who deny that it exists. But then also these, you know, these factual things, but also, you know, sort of the emotional aspect behind it of people being isolated and lonely and people losing their loved ones and not being able to, like visit them at you know, when, when they're in the hospital or when even in like a funeral, you know, you can't even hold a funeral anyways, those conjure up it's the word pandemic conjures up all this sort of like images for me, but also, I think, like I personally received a lot of support during the pandemic, from organizations and from others. So there's also that sort of positive aspect to it, that I think that we also found ways to still be social with each other with with each other, beyond, you know, sort of in person meetings and, and the amount of support that communities have sort of put back into giving back to their community. And, you know, I was I even received a grant to make a film during the pandemic. It was called immured queer emergencies by the Toronto Queer Film Festival. So there's a lot of like, you know, really good work that is happening during the pandemic. But so a little bit of both of you know, not so great, but great stuff. When you say, pandemic.

Kit Heintzman 04:20

Would you be willing to share a bit about what you remember about experiencing SARS?

Amanda Wong 04:27

Yeah, I mean, I was quite young during SARS. I was so I was How old was I? I was probably around eight or nine when SARS happened. SARS was like 2002-2003. Right? If I'm not wrong, so around that age, and I lived in Singapore at the time and we in school We were all given out. Each school child was given a free thermometer, an oral thermometer, and we would have to do temperature checks every day in school. I don't know if they had had, like, you know, the touchless head, contactless head thermometers back then I would assume that would be easier than giving every kid an oral thermometer. But I didn't really understand the the seriousness of what was going on, because I was a child. And I just remember, like trying to get out of school trying to get out of class by rubbing my thermometer on my clothes so that it'd be really warm, putting my mouth and when my teacher would come and look at me. And look, I have a fever when I don't actually so, you know, as a child, I didn't understand or I didn't grasp the seriousness of of that. And my grandfather also worked in a place that was hit with an outbreak of SARS. So it was very serious. And he was thank God, he was fine. But you know, I just didn't understand that. And I remember, you know, we had a, I think my mom had booked a, like a year in advance, it was like some kind of performance that we're supposed to attend in a theater. And she was she wasn't sure if we should go because of what was happening or SARS, I think was this was in the early part, where it was still sort of, I guess, we weren't sure what the consequences of it were. And we did end up going to it. And all I remember of this was that it was packed. And I couldn't breathe through my mask. And I was washing on stage, but I couldn't focus. And I was really excited to be there. But I just couldn't breathe through the mask. And I was wondering what was going on. And it felt really hot and stuffy and claustrophobic in the room. And and then I think, you know, my mom and I to this day, I think she said she really regretted going to because you never know what could have happened with that many people. There and and there were a lot of sort of, like, I think when we lived there, there was a lot of sort of very community like solidarity against SARS, like everyone was wearing masks, there wasn't this sort of like push back. Now with the pandemic, where some people like refuse to wear a mask, or at least if there were I wasn't aware with it, about it, because of the mass sort of release of thermometers and, and information. And on the TV there were like celebrities, you know, doing like SARS related things, which I guess they did a little bit at the beginning of this pandemic too. But, so that's just my, what I remember of it, but again, I was very young. So a lot of that is, like sort of through what a child's lens

Kit Heintzman 07:49

to the extent that you're comfortable sharing what have been some of your interactions with health and healthcare, infrastructure, and what have those been like, pre in staying in the pre pandemic world.

Amanda Wong 08:01