Item

Joya Ahmad Oral History, 2021/06/25

Title (Dublin Core)

Joya Ahmad Oral History, 2021/06/25

Description (Dublin Core)

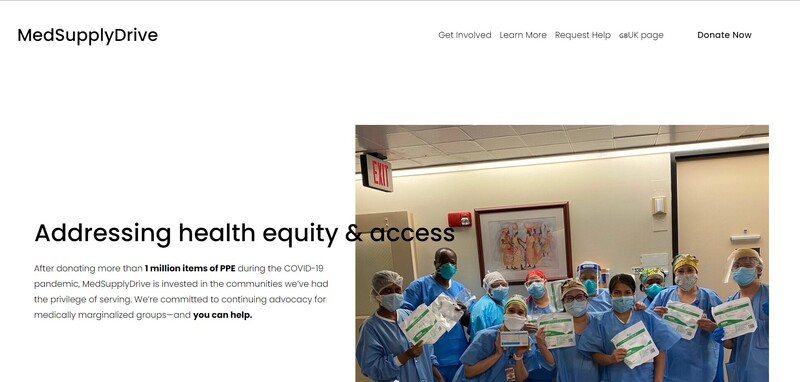

Self-description: “I think the most pandemic relevant thing about me is that I run a national nonprofit called MedSupplyDrive that does PPE donations across the country, as well as doing health equity education for high schoolers. So I’m one of the national logistics directors; I’ve been in that position since April of 2020, though I started working with the organization in March. So, I’ve been in this seat for kind of as long as the US has been experiencing the pandemic. The other hat that I wear that’s been particularly salient is that I’m a medical student, I’m a rising first year, and have been operating in various healthcare roles or healthcare adjacent roles: I was a scribe, I’ve been street medic, I’m a crisis counselor. I spend a lot of time in healthcare space and a lot of time in nonprofit PPE space.”

Some of the things we discussed included:

The pain, strife, stress of the pandemic, as well as awe at humanity and all that we did right

Healthcare as bureaucratic to its detriment; American healthcare as broken beyond repair; health as a for-profit business

Distrust in the healthcare system as a patient and as a provider, being a queer woman of color receiving healthcare

Working as a medical scribe and volunteering at rape crisis support worker

First hearing about the pandemic through friends in China

Cruise ships as an early indicator of crisis in the USA

The emotional need to help during the pandemic; deciding how to best help

Volunteering in the emergency COVID morgues in March and April; helping find and deliver PPE

Mr. Rogers, a Quaker education, Zakat, and parents as activists and influencing ideas about donation, charity, and service

Having people’s lives depend on you

Tutoring online

Giving up public transit

Moving in with partner during the pandemic in a studio at first, and then moving into a larger apartment

Friendships changing during the pandemic over ideas about safety and care

Comparisons between experiences working as a street medic at protests pre-pandemic and mid-pandemic

Militarization of the police and police brutality

Working in the morgues in trucks

What homelessness looked like during the pandemic with reduced shelter capacities

Losing work during the pandemic

Struggling with self-care, guilt

Being disabled and in community with disabled people and people who are immuno-compromised during the pandemic

CDC guidelines in theory and practice

Pandemic fatigue and watching people move from being quite cautious to less cautious over time; hearts and wallets closing

Universal compassion

Putting down roots

The danger of living in the USA 2016-2020, escalating racist harassment; the attack on the capital

The impact of trauma and anxiety on the experience of the pandemic; fight and flight responses; panic attacks

Rape culture

Saying goodbye to a dying friend

Pride weekend in New York 2021 and concerns about safety

Having friends and family in India and Bangladesh

Vaccine patents

Adopting two cats: Pesto and Gnocchi

Scientific vernacular and exclusion of many people; ivory tower; expertise and ego; poor science communication kills people

Marginalized people showing up over and over again to help not just their own communities, but also people in more privileged positions who haven’t showed up for those more marginalized

Donations; how far money goes in non-profits; money saves lives

Other cultural references: Zoom, Cassandra (the Trojan Princess), 9/11, the History Channel, Sohla El-Waylly, The 2017 Huffington Post article “I don’t know how to explain to you that you should care about other people”, Mr. Rogers, Staples

The pain, strife, stress of the pandemic, as well as awe at humanity and all that we did right

Healthcare as bureaucratic to its detriment; American healthcare as broken beyond repair; health as a for-profit business

Distrust in the healthcare system as a patient and as a provider, being a queer woman of color receiving healthcare

Working as a medical scribe and volunteering at rape crisis support worker

First hearing about the pandemic through friends in China

Cruise ships as an early indicator of crisis in the USA

The emotional need to help during the pandemic; deciding how to best help

Volunteering in the emergency COVID morgues in March and April; helping find and deliver PPE

Mr. Rogers, a Quaker education, Zakat, and parents as activists and influencing ideas about donation, charity, and service

Having people’s lives depend on you

Tutoring online

Giving up public transit

Moving in with partner during the pandemic in a studio at first, and then moving into a larger apartment

Friendships changing during the pandemic over ideas about safety and care

Comparisons between experiences working as a street medic at protests pre-pandemic and mid-pandemic

Militarization of the police and police brutality

Working in the morgues in trucks

What homelessness looked like during the pandemic with reduced shelter capacities

Losing work during the pandemic

Struggling with self-care, guilt

Being disabled and in community with disabled people and people who are immuno-compromised during the pandemic

CDC guidelines in theory and practice

Pandemic fatigue and watching people move from being quite cautious to less cautious over time; hearts and wallets closing

Universal compassion

Putting down roots

The danger of living in the USA 2016-2020, escalating racist harassment; the attack on the capital

The impact of trauma and anxiety on the experience of the pandemic; fight and flight responses; panic attacks

Rape culture

Saying goodbye to a dying friend

Pride weekend in New York 2021 and concerns about safety

Having friends and family in India and Bangladesh

Vaccine patents

Adopting two cats: Pesto and Gnocchi

Scientific vernacular and exclusion of many people; ivory tower; expertise and ego; poor science communication kills people

Marginalized people showing up over and over again to help not just their own communities, but also people in more privileged positions who haven’t showed up for those more marginalized

Donations; how far money goes in non-profits; money saves lives

Other cultural references: Zoom, Cassandra (the Trojan Princess), 9/11, the History Channel, Sohla El-Waylly, The 2017 Huffington Post article “I don’t know how to explain to you that you should care about other people”, Mr. Rogers, Staples

Recording Date (Dublin Core)

June 25, 2021

Creator (Dublin Core)

Kit Heintzman

Joya Ahmad

Contributor (Dublin Core)

Kit Heintzman

Link (Bibliographic Ontology)

Controlled Vocabulary (Dublin Core)

English

Politics

English

Community & Community Organizations

English

Health & Wellness

English

Protest

English

Healthcare

Curator's Tags (Omeka Classic)

2020 election

6 Jan 2021

ableism

activism

activist

anxiety

Bangladesh

bereavement

BLM

Breonna Taylor

Brooklyn

capitalism

care

cats

CDC

chronic pain

collectivism

cruise ship

Delta

disabled

disability

embodiment

George Floyd

guilt

healthcare worker

homelessness

India

kindness

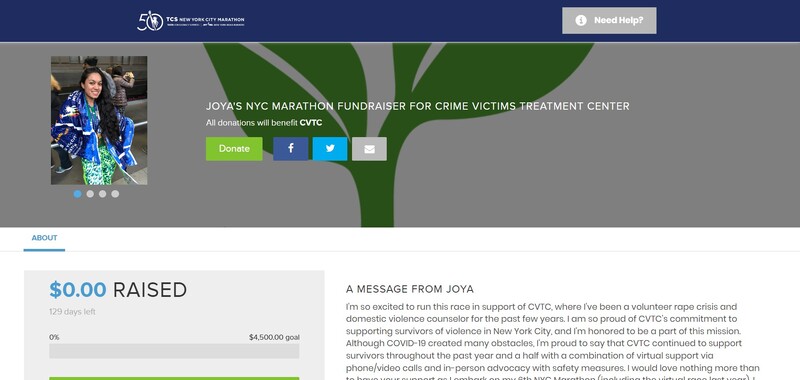

marathon

MCAT

med student

mental illness

morgue

neuroscience

New York

panic

partnership

patents

pets

police

police brutality

PPE

pride weekend

prison abolition

protest

public transit

online learning

online teaching

Quaker education

race

racism

rape culture

runner

sexual assault

safety

selfcare

slam poetry

street medic

student

teaching

therapy

trauma

tutoring

queer

violence

volunteer

Contributor's Tags (a true folksonomy) (Friend of a Friend)

politics

BLM

disabled

mental health

healthcare

student

nonprofit

teacher

Collection (Dublin Core)

Motherhood

Disability

LGBTQ+

Date Submitted (Dublin Core)

02/18/2022

Date Modified (Dublin Core)

02/24/2022

03/28/2022

04/22/2022

05/23/2022

01/15/2023

03/20/2023

04/06/2023

Date Created (Dublin Core)

06/25/2021

Interviewer (Bibliographic Ontology)

Kit Heintzman

Interviewee (Bibliographic Ontology)

Joya Ahmad

Location (Omeka Classic)

Brooklyn

New York

United States of America

Format (Dublin Core)

Video

Language (Dublin Core)

English

Duration (Omeka Classic)

01:45:53

abstract (Bibliographic Ontology)

The pain, strife, stress of the pandemic, as well as awe at humanity and all that we did right. Healthcare as bureaucratic to its detriment; American healthcare as broken beyond repair; health as a for-profit business. Distrust in the healthcare system as a patient and as a provider, being a queer woman of color receiving healthcare. Working as a medical scribe and volunteering at rape crisis support worker. First hearing about the pandemic through friends in China. Cruise ships as an early indicator of crisis in the USA. The emotional need to help during the pandemic; deciding how to best help. Volunteering in the emergency COVID morgues in March and April; helping find and deliver PPE

Mr. Rogers, a Quaker education, Zakat, and parents as activists and influencing ideas about donation, charity, and service. Having people’s lives depend on you. Tutoring online. Giving up public transit. Moving in with partner during the pandemic in a studio at first, and then moving into a larger apartment

Friendships changing during the pandemic over ideas about safety and care. Comparisons between experiences working as a street medic at protests pre-pandemic and mid-pandemic. Militarization of the police and police brutality. Working in the morgues in trucks. What homelessness looked like during the pandemic with reduced shelter capacities. Losing work during the pandemic. Struggling with self-care, guilt. Being disabled and in community with disabled people and people who are immuno-compromised during the pandemic. CDC guidelines in theory and practice. Pandemic fatigue and watching people move from being quite cautious to less cautious over time; hearts and wallets closing. Universal compassion. Putting down roots. The danger of living in the USA 2016-2020, escalating racist harassment; the attack on the capital. The impact of trauma and anxiety on the experience of the pandemic; fight and flight responses; panic attacks. Rape culture. Saying goodbye to a dying friend. Pride weekend in New York 2021 and concerns about safety. Having friends and family in India and Bangladesh. Vaccine patents. Adopting two cats: Pesto and Gnocchi

Scientific vernacular and exclusion of many people; ivory tower; expertise and ego; poor science communication kills people. Marginalized people showing up over and over again to help not just their own communities, but also people in more privileged positions who haven’t showed up for those more marginalized. Donations; how far money goes in non-profits; money saves lives.

Mr. Rogers, a Quaker education, Zakat, and parents as activists and influencing ideas about donation, charity, and service. Having people’s lives depend on you. Tutoring online. Giving up public transit. Moving in with partner during the pandemic in a studio at first, and then moving into a larger apartment

Friendships changing during the pandemic over ideas about safety and care. Comparisons between experiences working as a street medic at protests pre-pandemic and mid-pandemic. Militarization of the police and police brutality. Working in the morgues in trucks. What homelessness looked like during the pandemic with reduced shelter capacities. Losing work during the pandemic. Struggling with self-care, guilt. Being disabled and in community with disabled people and people who are immuno-compromised during the pandemic. CDC guidelines in theory and practice. Pandemic fatigue and watching people move from being quite cautious to less cautious over time; hearts and wallets closing. Universal compassion. Putting down roots. The danger of living in the USA 2016-2020, escalating racist harassment; the attack on the capital. The impact of trauma and anxiety on the experience of the pandemic; fight and flight responses; panic attacks. Rape culture. Saying goodbye to a dying friend. Pride weekend in New York 2021 and concerns about safety. Having friends and family in India and Bangladesh. Vaccine patents. Adopting two cats: Pesto and Gnocchi

Scientific vernacular and exclusion of many people; ivory tower; expertise and ego; poor science communication kills people. Marginalized people showing up over and over again to help not just their own communities, but also people in more privileged positions who haven’t showed up for those more marginalized. Donations; how far money goes in non-profits; money saves lives.

Transcription (Omeka Classic)

Kit Heintzman 00:01

Hello.

Joya Ahmad 00:03

Hello

Kit Heintzman 00:04

Would you please start by telling me your full name, the date, the time and your location?

Joya Ahmad 00:10

Yeah, my name is Joya Ahmad. It is Friday, June 25 8:36pm. Eastern Time, and I am in Brooklyn, New York.

Kit Heintzman 00:18

And do you consent to having this interview recorded, digitally uploaded and publicly released under a Creative Commons license attribution noncommercial sharealike?

Joya Ahmad 00:29

Yes, I do.

Kit Heintzman 00:30

Thank you so much. I just want to start by asking you to introduce yourself to anyone who might find themselves listening to this. What would you want them to know about you and the place that you're speaking from?

Joya Ahmad 00:43

So I think the most pandemic relevant thing about me is that I run a national nonprofit called Med supply drive that does PPE donations across the country, as well as doing health equity education for high schoolers. So I'm one of the national logistics directors. I've been in that position since April of 2020. That I started working with the organization in March. So I've been in this seat for kind of as long as the US has been experiencing the pandemic. The other kind of hat that I wear that's been particularly salient is that I'm a medical student. I'm a rising first year and have been operating in various healthcare roles, or healthcare adjacent roles. I was a scribe, I've been a street medic, I'm a crisis counselor. So I've spent a lot of time in healthcare space and a lot of time in nonprofit PPE donation space.

Kit Heintzman 01:34

Can I ask what the word pandemic means to you?

Joya Ahmad 01:39

That's a great question. That stumps me immediately, which was funny because I ask it to my high schoolers when I teach health equity classes about the pandemic. It means to me in the love logistical sense, something big enough that everyone's affected. And it also a disease specifically, in the emotional sense, it means. I guess like, if you can imagine the Loch Ness Monster, deciding that it lives with you, one day, that emotionally, it feels like I am now the home for a Loch Ness Monster of various things. The pandemic is so broad of a term that it becomes almost meaningless. But then every now and then it has moments where it means just so much that it is overwhelming. Most of the so much that it means is pain, strife, stress, and then a little like glimmer of it is all at humanity and the stuff that humanity did, right. But mostly, it's the pain of strife and stress.

Kit Heintzman 02:55

To the extent that you're comfortable sharing, would you be willing to say something about your experiences of health and healthcare infrastructure prior to the pandemic?

Joya Ahmad 03:05

Absolutely. So healthcare infrastructure has never been something that particularly impressed me I have always found it to be unwieldy, and in many ways like bureaucratic to a fault and on purpose. I've never really felt as a healthcare worker that the health care system serves me, I've never felt that it served my patients, I've never felt that it served my co workers, I've really always felt like it was this Byzantine system that like some French existentialist author dreamed up after a bad glass of absent, like, that's always what it felt like. And I felt a little bit distant from people who had still hopes and dreams about healthcare being a safe and functional space. And then after this all started, I think that's become more of a mainstream view that the system is broken beyond repair, and maybe never worked to begin with, or maybe worked in some really awful ways to begin with. So I've never, never had a lot of trust in it. I've always had a lot of respect for people who work in health care, along with a healthy dose of mistrust. I'm someone who works in healthcare, but I'm also someone who's been a patient in many contexts. I am a queer woman of color. That means that I don't usually get treated well and healthcare contexts. So I don't trust anyone without reservation, especially in healthcare. And I expect that that is how I am received as well. So when I enter a space as a provider, I'm always expecting someone to distrust me a little bit and willing and able to work for that trust, which I also don't think is a particularly mainstream view in healthcare. I definitely work with people who feel insulted when a patient doesn't trust them. I tend to feel honored that a patient is willing to trust me with letting me know that they don't trust me. I think that in and of itself is an expression of trust, but don't trust the healthcare system. I don't trust most systems, but I have a lot of respect for the people who work with him.

Kit Heintzman 05:03

Staying in the pre pandemic world, what was your day to day looking like?

Joya Ahmad 05:08

Oh, God. That's a fantastic question. What did my day to day look like? At the kind of right before the pandemic started at the very beginning tail end of 2019, early part of 2020, I was working as a medical scribe in an outpatient cardiology clinic. So that was my full time job. I was tutoring a million children in New York, which was an in person thing I kind of ran all around the city, seeing kids, different neighborhoods, different homes, I was always in people's homes, tutoring, I was still doing nights as a crisis counselor, I'm a rape crisis and domestic violence counselor with a nonprofit in New York. So I kind of meet people in the ER after an assault, and serve as whatever they need me to be in that moment. I don't do any medical care in that role. But I'm usually a liaison between the patient and the medical team. Sometimes I'm a liaison between the patient and the police. And mostly I'm emotional support. So those were all things that I did. And I was finishing my post baccalaureate program to apply to medical school. So I was finishing like organic chemistry, and studying for the MCAT. All of those things happened very much with other people. And we're in person. So I very much was a study group kind of person, I was always with my classmates, it was always with my peers. So my prepend and Demick, life was really full of people, and really full of going into a lot of different spaces, like I would leave the clinic and I would go to someone's house, and then I would go to someone else's house, and then I would come back to my own apartment. And so it was very, there was a lot of space sharing in my life. And what are some of the ways that you had to adapt with all of those different parts.

Joya Ahmad 06:52

I don't share space with people anymore. Not like that, at least, my role as a scribe was furloughed almost immediately when the pandemic hit, because that was very much a non essential part of health care. So that became the space that I had there kind of became filled by running this nonprofit and by volunteering in a few city marks, so that was something that happened in New York City, there were sure there have been many news articles about the giant refrigerated trucks full of people's bodies. It turns out that more staff is usually five to 10 people, even in a major hospital, they don't tend to have that many people on a daily basis. So there is a Medical Reserve Corps in most states, I'm a member of my states. And so when that kind of wave of deaths hit, one of the first calls was to the volunteers in the Medical Reserve Corps. So I became a more volunteer in end of March, early April, and kind of went to the morgue every day, instead of going to the clinic, which was very odd for my brain because it was the same hospital, there was the hospital that used to go upstairs in and then I started going downstairs. And so that was a very big shift in my life. And then with teaching, I kept tutoring, most of my students actually needed much more support when school went online. And I started doing it like this on Zoom, which in some ways was a blessing. I think zoom for one on one teaching has a lot of benefits. There's a whiteboard feature, you can screenshot the notes, you can work on a doc together, there's a lot of things that are very conducive, especially for you know, middle school and up I think is very conducive to one on one learning via zoom.

Joya Ahmad 08:30

Little kids, there's a limit to what you can do with a second grader on Zoom. So that definitely changed. And then I really just stopped going to people's homes, which was the biggest change for me. And it was weird because I hadn't considered how much people's security guards and front desk people and janitors were like a part of my life. But I gotten really used to seeing some of these people every day, or at least multiple times a week. These are people I knew, like I didn't just pass them in the hallway. Many of my tutoring students I've had for years on end. So I know the guy at the front desk, who's always there, the time that I get there, I know his wife, I know his family. I know his birthday, like we're friends. And so that was very odd to suddenly lose, not just my students in person, but all the people around them that I had come to know and realize how much I cared about the bus driver that I was used to. I used to take Crosstown bus to this one student like four times a week and the bus driver was someone that I talked to, like I talked to her every day almost and it had been three or four years. And it was very odd to suddenly realize that I wasn't going to do that anymore. So I had to adapt to feeling my circle shrink in ways that I didn't even consider my circle could shrink because I hadn't consciously realized how many people that I just said hi to or had brief conversations with in passing. I didn't realize how much that impacted my day to day routine until they were all gone all of a sudden. So that was a big shift for me. And then I took the MCAT. So that large amount of time left my life after I finished taking it. And then I started working at a tutoring company teaching for the MCAT. So the MCAT didn't really leave my life. But it took on a very different weight in my life because it was no longer something that was horrifying to me was something I was trying to help other people be less scared of, because I had taken it I was done. So that was like, it was a weird time to apply to med school for sure.

Joya Ahmad 10:30

Yeah, I think a lot of like space and time reallocation. And also my partner and I basically moved in together unexpectedly into my studio apartment. So we got real close, really fast, and had to navigate, both of us working remotely in a one room space, which meant we took a lot of calls in the bathtub. Let's call partnership meant to you over the course of the pandemic. Oh, it took on such a new meaning. My partner and I had been together for a while prior to the pandemic. And we always use the word partner, because that felt the most accurate. But then we started working in a nonprofit together. And we started running a central chapter of a national group together. And then they came on the board as well, just actually very recently. So now we're like on the board of a national nonprofit together, which is not something either of us thought we would ever do in our lifetimes. And now we're partners in a very literal sense. Like we coordinate things together, we delegate tasks to one another, we manage a chapter of volunteers, and set up drivers and ship things from Canada and call logistics people in Kansas, I did not ever think I would have the names of this many people in Kansas, but I do there's a lot of great logistics companies that run out of Kansas, they do a good job. And that to me, partnership means something very, very different to us. We've never worked together before. Not in that context. Anyways, we coach a slam poetry team together, that also went on Zoom. And so that wasn't a space that we were very comfortable in coaching together. But we'd never like run a thing, we never run a thing that people's lives depended on like slam is beautiful. And art is very much life saving for many people. But it is not the sole purpose of an artistic group to save lives not in the same way, like getting the hand sanitizer to Missouri today was literally gonna save people's lives. So it was like a very different level of intensity. I'm really grateful that I had a partner who was willing to do this with me.

Joya Ahmad 12:38

They're not a health care person. They've never been to health care persons them is not their world. They were an English major in college and are thinking about applying to law school. So very much different circles. And I kind of woke up one day and I was like, I got to do something like I can't. It's been a day and I can't take it. I can't take not helping I have to do something. And I found this group that was looking for a New York chapter lead and was like, I'll do it, what do I have to do and started cold emailing the whole world, asking for masks and building a fundraising strategy and building a, you know, strategy to get space to store inventory. And within a week or two, they were like, Okay, I don't know anything about these things. But I can Google and I can make phone calls. So what can I do? And that I think really shaped my understanding of them as a person, I did not expect that I wasn't asking them to do it. They were dealing with, they were still in school, still filling, finishing undergrad, I was very much expecting to like let them do their thing and have me do mine and support them as they got through the end of that and they had lost their job. And then they just showed up in a way that I'd never expected anybody to show up and took leadership in a way that I just never expected to see that in my like life partnership. And it was really beautiful. I'm really grateful. I think it's been polarizing for a lot of couples. I think a lot of people find out things that maybe they didn't want to find out about their partners or, you know, living in that small of a space together is a great recipe for a disaster and it wasn't a disaster.

Joya Ahmad 14:17

And I'm still a little shocked that we lasted that long in a studio, we did move when my lease ended, we were like not staying here. So we moved in our when we're in a larger place where we can have doors that shut which is beautiful. But I think we could have stayed I think we would have survived if we had stayed in a studio forever. And that was the first time the idea of if you were stranded on a desert island and you could only have one person to talk to for the rest of your life. Who would it be? I think the romantic answer is to always say your partner but I got proof that it is in fact them.

Kit Heintzman 14:54

I'd like to ask about sort of call to do something that you described. In the last example, I'm wondering if that feels similar to you in terms of the morgue work.

Joya Ahmad 15:06

Yes, it all kind of happened at the same time. I also feel like that was not a new emotion. For me as a person. I grew up in an activist family, both of my parents have been activists and use the word activist to describe what they do for a long time. I'm from Philadelphia, originally, there's a lot to do in Philadelphia, there's a lot of work to be done. And I did a lot of it growing up, I went to a Quaker school that really instilled in me this value of service. I didn't love everything about my quicker education. But it did love that. And so to me, doing community service in some way, is equivalent to like, paying rent, it's like a thing that you do in order to live in the place that you live. And for me, when the pandemic started, that was just the natural impulse like that is what I did, when the first wave of like large black lives matter protests started years and years ago, the first time we saw those uprisings get that big. My first instinct was like, Okay, how can I help? What do I do here? What are my skills? And how are they useful to another person and I became a street medic, then. And then when the kind of wave of uprisings happened last summer, that exactly what I did. I was like, Okay, I have my kit, I have my jacket, I have a helmet, let's go. And then, you know, the NYPD started really targeting medics, and we all stopped wearing identifying features after that, but that's very much who I am. And so it was not unexpected for me to have that feeling of like something awful has happened. And I need to act right now. And it needs to be useful. And I think that's the biggest thing that I watched people struggle with in the pandemic was, I want to help but I don't know how, and people diminishing the skills that they did have, and wanting to act in capacities that they actually just weren't suited to do. And there are just some things that I'm not going to be good at. So I'm not going to do them right now. Like I can learn in a less pandemic time. But I kind of took inventory the way that I always do, like, what can I do what is needed? Where's the overlap, and I saw it in someone who can deliver things, someone who knows enough people in health care that they can get contacts, because the larger systems, we're not accepting things were banning people from bringing their own masks or telling their nurses to wear trash bags. So we had to give things directly to physicians and nurses and techs. And that is a network that I have. So I was like, right, this is the right match for me. And in the morgue. The call was actually are you relatively small, have good upper body strength, and they're not afraid of the dark. That was the language in the email, because the trucks are very narrow. And so what they were realizing is the larger people who worked typically, it's larger, stronger, people with very big muscles who work in the morgue, and they physically weren't fitting properly. And it was becoming dangerous for them to walk sideways and try and carry someone in those very narrow aisles. So they were physically looking for people who could fit in that small space. And I was like, That's me. small, scrappy, not afraid of dark. And that kind of all was basically like the normal version of myself with like the volume turned up in terms of urgency.

Kit Heintzman 18:27

I was wondering if you would talk a bit more about what it meant to be a street medic in the context of a protest during a pandemic.

Joya Ahmad 18:38

Yeah, it was new. I'll tell you that. I street medics. For anyone listening who does not know what that means street medics are people with medical training, who give first aid on the street, pretty much they do not belong to any organization. They are not paid by anyone. They are volunteer people who show up and help when help is needed. That's kind of the point. Street medics exists in some more official manners in terms of like street medicine, outreach programs exist, there's a lot of homelessness care that goes on through street medicine outreach, those are typically not the same people who would call themselves a street medic, a street medic is usually just like a person. There are some unofficial groups that exist to keep us together. There are, you know, group chats, but that's about as far as it gets, because the majority of the care is done at protests, and the majority of the organizing is done around protecting protesters and helping survivors of police brutality. And so it is decentralized on purpose. That is the whole point of the network. And so being a street medic in New York in protest situations is not new to me. The level of violence was new. For me. I had not. Seen, I had not seen such malice and pre determined violence. Because in you know, so seven years ago in 2014, seven years ago, they a there was a curfew was a very new institution. For my experience in New York, that kind of curfew was new. And the purposeful trying to keep people out after curfew I had never seen before. There was a lot of like blockades on protest routes so that people couldn't leave. And then they would be forced to be out after curfew. And then the police would cattle and like, crowd everyone and make mass arrests. And so that was something I had never seen in America before. I definitely seen it. Definitely heard of and seen it in Bangladesh, which is where my family's from. But I never seen it done hear quite like that. And so that was very new. The level of mental gymnastics we had to play about risk assessment got infinitely more complicated because of the pandemic. And because, okay, yes, we're outside, people are breathing hard and shouting, and we're wearing masks, but not everyone is and testing has never been enough. Like we've never done a good job getting wide coverage of testing. A lot of police officers did not wear masks, and they like to get in people's faces screaming with spit as one does.

Joya Ahmad 21:30

So that that added a very new twist to like how we were deciding how close to get to people and what we were going to do and say and how much we were going to keep our distance and instruct people to do things and walk them through things versus go and give hands on aid. There were also just a lot more weapons that were used in these protests than anything I've seen before. It was a lot more tear gas, there were a lot more pepper balls, there was the L they brought the L rod out which I was not expecting. And I don't think people realize that a sonic weapon is as damaging as it as it is. So I definitely cared for a lot of people who didn't realize how much and they didn't run, because they were like it's just sound, what can it do. And then this massive, like wave of sound can really hurt you.

Joya Ahmad 22:17

It was a very, it just added a lot of layers of complexity to what is typically a very straightforward job. And we also saw people getting hurt, much worse. And so that added the next layer of complexity of Do you go to the hospital? And if you do, where should you go? Are they going to follow you? Are they going to find you? Where can you go to get help? And so that became a very difficult set of questions and conversations to have and there's no perfect answer. And some people chose to go to the hospital and risked being arrested if they were found there. And some people chose to go home with injuries that they probably shouldn't have gone home with. And then on top of that, a lot of the protests came through many areas where there were a lot of homeless encampments. And in New York City, the shelters went to 30% capacity in I think late March, early April. And that meant that in a city where 95% of the homeless people in New York do have shelter, cutting shelter capacity to 30% meant a lot of people were suddenly homeless and unsheltered, which is not how New York's homelessness typically looks. And it's very different in New York than it is in LA, for example, because this is a right to shelter state. So losing that shelter capacity really changed the dynamic on the physical streets and in the parks. And protests often overlapped with those areas, especially because there are a lot of homeless encampments right around where central booking and the kind of One Police Plaza area is in Manhattan. And so that was also an area of worry of, we need to also attend to the community members who may or may not be a part of the protest, but are here and they live here. And they were also needing extra care. So we kind of split into two groups where we had people who were running at the protests and people who were sitting and taking care of both protesters and community members who were living in or around those parks. And that became kind of an auxiliary arm we started doing a lot of jail support setting up 24 hour shifts to wait for people being released, because people would come out with a lot of injuries or just disoriented. And so that really changed the dynamic of street medic gang because I started to see people repeatedly as opposed to buddying up with a stranger for a protest and then never seeing them again, never knowing their name. And it really changed the dynamic. I now know many of my fellow medics much better than I did seven years ago. It was weird to reconnect with people in the same chats after seven years and be like hey, I remember you we Bronx, Manhattan, Queens, where were you which I'm trying to place you but it really changed what street medic work looked like. Because usually shelter. Were there. And then all of a sudden, they weren't.

Joya Ahmad 25:06

Or they were for 30% of the people, but it got much more stringent. And rules about belongings often also got much more stringent, which meant a lot of people would choose not to go to the shelters because they would have to lose 50 60% of their stuff. And sometimes they lost it anyways. But that was definitely different. And I had a lot more interaction with police, as a medic, because I did a lot of the jail support work where I was just sitting there and like cops couldn't see me with her eyes. And so I definitely interacted more with police than I would have in a more like protest only anonymous setting. And that was uncomfortable to say the least they were not happy with our presence there, they did not want that care to be present.

Joya Ahmad 25:55

I did not ask them why I chose to let them make their statements. And I did not really respond. But there was a lot of animosity towards the presence of people doing things like patching up people's bruises and cuts and offering people food and coffee. And that was really not was not smiled upon.

Kit Heintzman 26:17

Would you tell me a bit about what you remember about first hearing about the pandemic, sort of what initial reactions looked like and felt like?

Joya Ahmad 26:27

So it's interesting, because I heard about it first, very early. I have a lot of good friends in China, and or here with family in China. So the sources of information I had, and have had, in general have never been exclusively American, which means that they look very different from a lot of what I see on American news. And so I was kind of bracing for it. By mid January. I was like this is coming here. It's coming here and it's going to be bad. I did not think it was going to be this bad. But I was like, I I don't see this ending Well, I just don't see this ending well. And so it was not a surprise to me. I think the first thing I heard was like a article that someone sent me like a translated article, someone sent me about one. And seeing that and being like, feel like this is how the plague started. feel I feel like this is I just feel like this is how the plague started in the 1300s. Like it, it feels very familiar. And the first like, American freak out, I remember was I think it was one of the cruise ships that I knew someone who knew someone who knew someone, like one of my co workers knew someone who many degrees of separation, he was on one of the cruise ships. And then people were like, Oh, this is gonna get really bad. And then some group chat informed me of the first New York City COVID positive patient because 85% of my circle is in health care. And then I got the email from my post bacc program that, you know, if you feel sick, stay home. And then like two days later, in March was like the lockdown where they were like, nevermind, everyone go home.

Joya Ahmad 28:13

We're going online for the rest of the year. And and then like, everything happened really fast after that. So that was I think like March 13, or 12th, or something like that. And then like two days later, my MCAT day got canceled. And then two days after that, my scribe job evaporated. And then two days after that I was running the New York City Chapter of med supply drive. Like it all happened in the span of like a week. But I think I felt less taken by surprise than a lot of people in my life because a lot of people called me the day that everything shut down. And they were like, what's going on? And I was like, I mean, nobody ever reads the articles, I send them. But that's fine. It's a plague, y'all like it's a plague. This is a plague. And we live in it. And those of us who are in New York City, we live in it like this is the epicenter of the epicenter, and it's not going to be fun. So like, buckle up, buckle up. It's the apocalypse, I think is an actual phrase that I uttered in a conversation with someone who was like, it's gonna be fine. Like, I'm not going to cancel my flight in May and I was like, You should cancel your flight in May, you should get your refund now.

Joya Ahmad 29:28

I felt very much like Cassandra at the beginning. I was like, no one's listening. I'm telling the truth. But I think my perspective is also informed by the fact that I have a lot of friends who are disabled and immunocompromised. And they were looking at this with a much higher level of urgency than people who felt themselves to be invincible people in their 20s and I myself have a lot of health issues. So I was looking at this like, very suspiciously from the get because I don't trust this country to Take care of each other at all. I do not, I did not at that point, and I still don't, but slightly less, I really didn't trust our government then to do anything, right. And so I think the level of like heightened vigilance was different. And it always has been different in disabled communities than it is enabled ones, it's always going to be that way. If you know from the get that you like, can't trust the world to take care of your body or to treat your body with respect that you are going to view things with a lot more scrutiny. And so that is very much the perspective that I was coming from. So I think it was not a shock. I was a little shocked by how poorly people responded. I more so than the beginning of the pandemic. I remember the first like anti mass protest I heard about, and I was flabbergasted. I was I was beyond bewildered. I was like people are protesting what they're going where to watch like i, i, Pretty sure I like laughed, cried for a while. The first time I heard about one of those I was like this is we're doomed. I was like, we're we're like humanity had a good run, didn't have a good run, humanity had a terrible run. And it's, it's over, like pack it up, guys, if this is what we're doing. Wow. That was the thing that I think hit me like a ton of bricks, the actual announcement that we were in a worldwide pandemic, and that it was going to kill a lot of people did not surprise me, it scared me. It made me very sad. I mean, very worried. It made me very inclined to action, but it did not surprise me.

Joya Ahmad 31:42

The sheer levels of selfishness that I shouldn't have been surprised. I've lived in America long enough. And and yet, a little piece of me was like, we could be good to each other. Right? And then we couldn't. And I was like, Oh,that one hurt.

Kit Heintzman 32:09

Would you talk a bit about how some of those reactions have changed over time? And or and or how they've stayed consistent?

Joya Ahmad 32:17

Yeah, I think I think it's gotten more confusing people's reactions now. And I think some of that is the guidance from the CDC being like, you don't need to wear a mask if you're vaccinated. And then a lot of businesses have taken that to be like, no more masks. And I'm like, that maybe isn't the greatest idea. But I've seen a lot of people who took it very seriously early on, starting to not take it seriously anymore, and not wear masks and fly for non essential reasons and go and eat indoors. And like lots of things, a lot of people that at the beginning were like, very, very stringent about following the rules, like the people who were sanitizing their Doritos are now like sharing bowls of Doritos with strangers and bars again. And that has confused me a lot. But I think I overestimated the lesson learning that was going to happen. I thought once we got to everybody knows somebody who's died points in a pandemic, that there would be a collective like this is very serious. And we need to start being overly cautious as opposed to hedging our bets and kind of winging it, like we need to be willing to be called over reactors now that we've seen this.

Joya Ahmad 33:38

And I think I overestimated people's ability and willingness to learn from that. I think I also overestimated how people whose circles were very small and privileged, I overestimated their ability to like, understand outside of their circles. And I think it's just really different. I don't think there are a lot of people outside of healthcare, and who get what it looks like inside hospitals. And even within healthcare, I think there are a lot of people healthcare, maybe is the wrong group to say here because there's a lot of outpatient practitioners who were like my, my practice is online now and I'm fine. I think hospital based practitioners, and mortuary workers saw something that no one else saw. I don't think it's possible for me to take it lightly anymore. Now that I've carried so many people's loved ones in a bag, like you don't forget that. And I've dealt with death before I've handled decisions before but the number of bodies that I moved was overwhelming. And stalking people people these were people to to a shelf in a truck that doesn't leave you Ever, and it puts everything into a very serious light. So that I find myself feeling very at odds with people who are like, it's time to open up again. And I'm like, why are we so eager. There are also just like, from a scientific perspective, there are variants, we do not know how these variants are going to respond to the vaccine, we do not know if the vaccine is even going to last very long. It's a new vaccine, the tetanus vaccine needs a booster and we've had that forever. So like, maybe just slow your roll. And people are like, it's time, we need to have fun again. And I'm like, I don't know that my ability to go to a bar is worth whoever's Grandma I carried into a truck last year. And I am going to keep wearing masks. And I'm going to keep not eating in indoor restaurants. And I'm going to keep seeing people in parks, which I actually have really enjoyed that most of my interactions with my friends are now very outdoors based. I think that's lovely. But I think the group of people who now don't wear masks and do whatever has broadened to the extent that I can't tell them apart anymore. And that's confusing.

Joya Ahmad 36:14

A lot of people have talked about pandemic fatigue, and the like quarantine fatigue of like, a have just been inside too long, I just have to get out, and I don't get it. I intellectually understand how one could become fatigued with that. And I understand how monotony can really wear on the soul. And from my perspective, if you had the privilege to genuinely just be in one place, and not have to move and not have to go outside not have to do anything. You're living a charmed life. And I wish everyone could just like come sit on my shoulder for a day. I, at the beginning of my tenure as the New York manager before I became part of the national group. We didn't have volunteers yet. We had me. And so I didn't have a car. I don't have a car in New York City, most people don't. I was running with boxes of masks, like I was taking backpacks of masks and gloves and running to Queens, like I was running 1520 miles a day to frantic healthcare professionals who were on their last mask or who had already gone through, you know, six reuses of the same one. And then someone coughed on it. And now they couldn't use it anymore. Like I was meeting people in tears outside of their hospitals at four o'clock in the morning, like, I was running like people's lives depended on it. And they did. And I just I was tired. I was very tired. I was so tired. I got a city bike membership, because I was like, this isn't sustainable. At a certain point. I was like, I can't run this much. I will break. So I biked that much instead, which was also very tiring. And I woke up most mornings in the middle of a panic attack. Because I was so afraid I had slept through a phone call. What if somebody called me in the middle of the night, and they needed my help. And I didn't pick up what if, and that tortured me for months. And I'm a lot better now. Our structure as an organization is much bigger, which has really taken a lot of the load off of me, but Nanos, that first summer, I felt the weight of New York on my shoulders every minute of every day. And so I found it really hard to understand what people meant when in still 2020 Like in the fall, they were like, I'm too tired of this, I have to, I have to go on vacation, I need to fly in a plane and I was like, need, oh my god, we have very different understandings of the word need. And I try to like, Hold compassion for them in my heart, because I know that their perspective is not my perspective and their experience is not my experience. And some people are just selfish.

Joya Ahmad 39:00

And I don't try to spend a lot of energy parsing out who's who I'm just like you're doing what you're doing. I don't love it and there's nothing that I can do to change your mind about it right now. So I'm just gonna keep helping who I can help and hope that you make peace with whatever you believe in one day but the thing that you believe in is clearly not make sacrifices for the greater good. And that is foreign to me. It's like it doesn't it doesn't mesh with my worldview. And so it mostly just makes me really sad. It makes it made me so sad to hear people be like, I need to go and danger a bunch of people and myself to like, go on vacation.

Joya Ahmad 39:50

And I just like I could never and I still can't really wrap my head around that like need and maybe I just use the word need very, very. Literally, but I think there's some distance that grew between me and my friends who operate it that way. There are some people that I just don't really know how to relate to anymore. I don't really know what to say to them.

Joya Ahmad 40:18

And I don't think I want I don't think it's a conversation I want to have with these people, none of the people who I feel that distance with are my very close friends, all of my very close friends, I realized they're very different from one another, the thing we all share is the I will sacrifice for the greater good vibe that I found, finally, the unifying feature of my incredibly disparate group of friends. And it's that, so I'm grateful for that, that I didn't lose any central friendships in my life. But some of the peripheral ones I was, like, keep you at an arm's length for I don't really know how to, I just don't know how to talk to someone who was so cavalier about other people's lives.

Kit Heintzman 41:03

2020 and 2021 have been big years within the context of the pandemic. They're also big years at another at a number of other intersecting issues. I'm wondering what some of the bigger issues of the last two years have been that have been on your mind?

Joya Ahmad 41:22

Absolutely. I think the 2020 election was a big one. I think being living at the intersection of a lot of marginalization meant that 2016 to 2020 was just, it just felt dangerous. Everything felt dangerous all the time. And I have a very significant amount of privilege in terms of education and access. And I still felt like I was in danger all the time. And I was like, in a very concrete sense, like I got followed, harassed, screamed at spit out more in those four years than ever before. And that includes right after 911. Like that was the last time I remember being hated that much, and being afraid of everyone on the street.

Joya Ahmad 42:12

I hadn't felt that way since I was nine. And then the 2016 election happened. And I was like, Oh, I don't, I'm not American to most Americans. I was born here. I was raised here, pay my taxes here have been serving, not just living in but like I've been actively serving my community in America for 28 years. And I think at this point, the majority would probably look at me and be like, go back to where you came from. And I got a reprieve from hearing that language consistently. After, you know, I think maybe like 2003 2004, the anti Arab sentiment had kind of chilled a little bit. I'm not Arab either, which is irrelevant to racists, but 2016 hit and it all kind of came flooding back with a twist, which was that people started to think I was Mexican, which was fun, because then I got to for the price of one in terms of racist slurs. At this point, I've developed a sense of humor about it. Like when someone would call me an Arab related slur, and I let the next related slur in the same breath. I'd be like, You got to pick buddy, which one is it? And they'd be like, huh, and I'd be like, Wow, it's a game show. Don't you know, guess the immigrant.

43:27

But I was exhausted by the time the 2020 election came around. I was genuinely devastated. In January when the capital attack happened that I'm glad that it didn't spark a series of things because that was my fear that day. I was like, this could be it. This is like, this is how the purge movies start, I think. And I felt very scared in that moment. But I'm very grateful that it didn't go much further than that. So I think that was one just like Trump's presidency and all of the things that happened and all of the kind of ripple effect things that happened as well, aside from just policy and the truly unprecedented amount of anti trans legislation that's been just flooding every state and the scary amount of anti choice legislation as well like, all of that, aside, the like larger cultural currents that began to feel a lot like riptides. Those were the things that I think shook me the most, because I knew that they weren't going to go away when he lost. And I was not sure that he was going to lose either. I was up all night for many nights, and I felt like Steve Kornacki by the end of it. I never resonated so deeply with a person on television than him like madly scribbling on his maps. I was like, Steve, you understand me? My partner. I like doing math on index cards were freaking out. And that really felt like life or death at that. And it was. And so that was a big thing. And then not just George Floyd. But the series of kind of high profile murders that happened or were discussed all at the same time, like Ahmed Aubrey died many months before, but kind of became part of that conversation. And same thing with Briana Taylor becoming part of the conversation like that series of uprisings was a huge cultural moment, I think for everyone. And for me, it was a very concrete reality because I was there, like I was wiping up blood on the sidewalk by day one, and that I've never trusted the police. I did not I didn't like even as a child, like I didn't grow up being told, if you're in trouble, find a cop. I was told if you're in trouble, find a woman with a stroller. Like find a mom with kids. That's who you trust, trust no one in uniform, any uniform, because they are more their uniform than they are the person inside of it. That was what I was taught from day one. And so I never had any trust for the police. But they became like cartoon villains. In the summer of 2020. Like I saw someone get dragged off of his own stoop, and arrested for being out after curfew. It was his property. And they just walked up the steps and dragged him away from his screaming wife and children. And everyone was just like, what is happening here? Like, there was just no, there was kicking delivery drivers, they were punching people in the face, like it was insane. It was it was like something out of a horror movie. And that I think changed the way that I operate in the way that I moved through the city now, because there are cops everywhere the police presence in the city has never gone down from last May. And I have always been wary of cops. I'm way more wary of cops now. I think there's a lot, there was just a lot of a lot of very graphic violence that I saw up close, and a lot of moments where I made a split second decisions to risk my life and go in after someone who was clearly visibly injured. And every time I did that, because I was applying to med school at the same time I was having this like fear of like, What if I die? What if I get blinded? Because they were blinding? A lot of people this last year, I don't know when they started doing that. And what if I don't die or get blinded, but I get arrested. And I lose? Ever I lose my everything is very, very difficult to get into medical school with a with a criminal record. And I was terrified the whole time and kind of had that conversation with myself every time I was taking a shift that was at an active protest was like, am I going to do this? Am I not going to do this? Why are you doing this? Is this a good idea? You know, are you going to be more useful to someone in another capacity. And the answer kind of every time was I'm small, I'm non threatening, and non block that gives me power in that space. And I have to use it. I couldn't live with myself if I didn't use it like that is those moments of going in and trying to take people out of a violent situation. Those moments were all decisions that I made because I had the privilege to live long enough to make them I had the privilege to stay out of jail long enough to make a decision to decide to put myself at risk instead of just having risks thrust upon me. And that I couldn't, I don't think I would have been able to face myself or any of my students ever. If I hadn't gone in and helped people I would have, I would have betrayed the actual community that I'm a part of. And I think for me, as a transplant to New York, I'll always say that I'm from Philadelphia, but I've been my entire adult life in the city. And these this is where my adult roots are. And turning my back on protests, given the privilege and access and physical ability that I had, would have made me feel like I was ripping up those roots.

Joya Ahmad 49:21

And that was part that was scary. That was really, really scary. And I think that really changed a lot. I think it also made me read a lot more and listen a lot more and ask a lot more questions about abolition in the concrete. I've always been a prison abolitionist, as person in theory. I don't really know what it meant, besides like, the concrete actions of like divesting from private prisons that I've bothered my own college about for years on end until they did like, but I never really sat with any groups that were talking about. How do we make that a reality like what will it look like to keep communities safe. What does this non carceral care look like? I had heard the phrase like health care is carceral many times and I'd seen ways, especially in mental health where it is, but hadn't given, like concrete specific thought to a lot of these things. They were things that I knew and believed and supported. But I hadn't seen them come into concrete reality before in front of my face. And like, the street medic and jail support collective became a very great example of non carceral health care, and presented us with a lot of challenges. A lot of like, I know that this person is making a decision that I don't medically agree with, and I cannot force them to do something. What does that mean? How do you negotiate with that?

Joya Ahmad 50:46

I think I learned more in the last year about healthcare than I will learn in four years of medical school. I think systems and theory wise, I don't think I'm gonna learn more than that. I think I'm gonna learn physiology. I think I'm gonna learn pathophysiology and anatomy and all the really important stuff it takes to be a doctor. But I think the really formative healthcare experiences that I had were on the street this year, for sure.

Kit Heintzman 51:15

Would you tell me what health means to you?

Joya Ahmad 51:19

It's a thing, insurance companies can charge you to try to keep a tenuous grasp on, I think health. Health means ideally, health means maintaining a body that is safe and comfortable to live in. In reality, health is a commodity health is a construct and health is a business. And I think disability complicates what health means. And on learning, the idea of normal or baseline is a very core part of what disability justice is. And I am entering healthcare as a profession, with an understanding of health as a construct on purpose as a person who believes in the tenants of disability justice, and will act on those also, as a person who is disabled and will live like that. So I think health means almost nothing. To me. As a word, I think it's become meaningless. I think the words I'm more interested in asking people rather than like, Are you healthy is like, Are you safe? Is there anything that I can do to change? That if you feel unsafe? Are you comfortable? Is there anything I can do to fix that? If you're not? Are you fully embodied? Like, do you have access to the parts of yourself in a physical way that you want to? Can I change that? If not, like, I think that's, that's the set of questions is, are you this? And can I help? Those are the two questions that I want to ask. And I don't think I've ever had the desire to ask someone like, so are you healthy. And I think that's been interesting, because that's become everybody's sign off in emails now is like, be healthy. And I'm like, never have been never gonna be. But like, it's, that's a weird thing to say to your boss. So I don't, but I always sign off with Take care. Because that's what I mean is like, I hope that you take care of yourself, or receive care for yourself in whatever way that looks. But I'm not healthy. Most of my friends are not healthy. And most of us are never going to be healthy. But I'm safe. And I'm as comfortable as I'm going to be. And those are the things that matter to me. I'm very connected to my body, like it or not, it exists and I'm able to access it, and fight with it and nurture it or not, and have complicated discussions with myself and my own doctors, and my own therapist and my own partner about like what taking care of a body means when that body's never not in pain. I have a just chronic pain all the time. And so I don't think I've felt well, ever, which is both exhausting, and kind of liberating. I think it's been.

Joya Ahmad 54:17

I was talking to a friend of mine who, like me is a very anxious person. And we were like, This is our time to shine, man. Everybody's anxious for the first time we've been here. We live here. This is like you're in our neighborhood now. And that was a joke, but also true that I was not fazed by needing to suddenly be constantly vigilant about everyone who came into my space. That is what having anxiety and having trauma means. I've always scanned every room for the easiest way out. I've always known exactly which thing I would reach for a weapon first, like that is how I exist as a person who's survived many things. And so I think there was a level of of liberation and a level of pride that I took in having a disabled self. Because it gave me a perspective and a resilience that I wasn't expecting to need. But then it kind of came through for me. So all the things that I was like, Oh, I'm so frustrated, but my body's always in pain. I kind of was like, Well, I mean, I do know how to live with it. And that is something that a lot of people are learning for the very first time and a lot of people aren't learning and are choosing not to be alive to learn it anymore. And I think there was a readiness, both physically and emotionally. That was not a pleasant thing to come by. But I ended up deciding to be grateful for it because what other choice did I have?

Joya Ahmad 55:47

Yeah, so health means nothing.

Joya Ahmad 55:51

safety, comfort, autonomy and embodiment mean everything.

Kit Heintzman 55:58

Would you tell me what safety means to us some of this has already happened but just inviting you to dive into it.

Joya Ahmad 56:05

Safety means I can sleep with both eyes closed. Yeah, that's my definition of safety is when I can go to sleep and not have whatever Sentinel part of my brain is awake scanning, when I can fully go to sleep, that safety. When my cats like roll on their backs, when they feel really safe, they let you see their like soft belly, that emotionally is also safety. I think being with someone that I can roll on my back in front of that safety. In a larger state, like living somewhere where I do not fear violence would be safety. But I've never experienced that. I have never walked on the street and been like, I'm not afraid of being assaulted. today. I'm like, I walk past men every day. And a fair number of them say something, do something or say and do something. And that's just my reality. It's been my reality. As a child, it's my reality as an adult, like, as soon as you're identifiably female from a distance, there are people who will harass and attack you, I have learned a lot of defense mechanisms. I'm very grateful that I have the physical ability to fight I did martial arts for a very long time, at a competitive level and boxed and I do actually feel confident and have proven to myself in dire situations, I can fight my way out of something if I need to. And I became a distance runner for a reason. If I can't fight you that I'll run away from you, those, those are the options. So big picture, I would love for safety for me to mean, I walk down the street, and I'm not using my phone as a mirror, I go somewhere alone at night, and I don't share my location with anybody that would feel very, that would be safety. It is not for me, for me, the closest I get is in my own home, in my own space with my cats with my person. That's safety. I think safety in my body would be believing that it's not going to fail me or break or dislocate or collapse. And that's a more tenuous relationship, there are times that I feel safe and like I can trust my body to support me. Running is a really big part of how I access that it's both something I love and something that has been has clearly supported me in my health, whatever that means. But like, there are many times I've had physicians tell me like, I'm really glad you're a runner because XYZ probably would have happened if you didn't have that stamina if you hadn't developed your cardiovascular system in this way. If you didn't build the muscular girdles around your joints this way you would probably be a lot worse off. So safety also means running for me. I think I feel safest when I'm in motion, which is something to unpack in therapy probably. I feel safest when I'm running I feel safest one. And with my cats I feel safest when my partner's home

Kit Heintzman 59:10

With that beautiful and capacious framing of safety. Under COVID-19, there's been an incredibly narrow idea of what safety means. And I'm wondering within that narrow framework, how have you been negotiating those kinds of particulars with people in your life around you?

Joya Ahmad 59:35

Yeah. I would love to be named an overreactor. At the end of all of this. I've never ever been afraid of being called someone who took it too seriously. I'm like, great. Bring it because you know what that will mean? It will mean that you just weren't at risk. That sounds great. So in the in the very literal sense. I don't have a problem with masks. I don't. I think I might like them. Like I think I genuinely enjoy them. I find it nice and no one can see my mouth. No one tells me to smile. They do tell me to take my mask off. And I don't but it's like there's a protectiveness about it in an emotional way that I love. But I wear masks. I don't go indoors with people who are not my partner. And if I do for any reason, we are also masked the only people that I spent time with unmasked. I lost a friend in this this April. And she was she was dying of brain cancer and kind of did a last hurrah drove her family drove across America to go be in Colorado with where she kind of grew up with her extended family. And she asked me to come out and kind of be for her at the end, and we did not wear masks in the house. And that was that felt safe. And we had kind of made that decision together as a group, that by the time I got there, they would have all been just with each other for several weeks, I quarantined in a hotel before I went, I was tested, they were tested, we were all vaccinated. And for something like that is where I'm like, this is where I'm, I want to take that risk. And that's why I'm so much of a not risk taker in every other space in my life, that if the moment comes, that I need to be present at somebody's deathbed, I want to be able to take my mask off and give you a kiss goodbye. And so I keep my mask on everywhere else, just in case. There are elderly people in my neighborhood that I interact with when I deliver food. And so I'm very, very conservative. I am not hugging people really, because I know that there's a chance I'm going to interact with a patient and have to touch them. And I don't want to be bringing anything with me. Hitting especially because I work with a lot of people who are homeless, they're already at risk for so much. I just don't want to be another risk factor. I don't want to be a vector. And I just think it's considerate to do that. So the particulars of safety, I've just taken the most extreme version of most of them. So that when I need to bend that rule, I can and not feel worried that I'm introducing something that's kind of my most important thing is like there are enough people in my life, who something could happen to that, I need to know that I've done everything outside of that, to keep myself as germ free for them. I also really like not catching colds anymore. So that I'm going to keep I also think it helped my lung capacity I ran with a mask on and still run with a mask on for over a year now. And I really think it helps. So I'm a fan of it.

Kit Heintzman 01:02:50

How are you feeling about the immediate future?

Joya Ahmad 01:02:53

Immediate, like tomorrow or immediate like the next couple months, either. Tomorrow, I'm feeling stressed about its Pride weekend in New York. And I love my glittery queer brethren as much as I possibly can. And I really don't want everyone going out to bars. I'm so freaked out by all the pride events that are happening. I don't want to go to the parade. I want to sit in a gay circle 20 feet apart and yell bad Tumblr memes at each other. Like that's it. I'm I'm a bad example. Because I don't like parties. I didn't like them before. I don't like them. Now. I like relationships that are based on conversation. I like to talk to my friends. I don't like to be in loud places. But I'm extremely stressed about pride this weekend. I'm a little frustrated. Like I understand like I'm I am also gay and want to go celebrate being gay loudly in the streets. And I'm like, really? The bars, please don't go No. It just like that I have so much anxiety about like all my friends getting the Delta variant this weekend. That that's my fear. The next few months, I am cautiously optimistic about I start med school in August. I'm excited. I've wanted this for a long time. I am shocked that it worked out this well during this cycle, which was both awful and very competitive, like more people applied to med school this year than ever before. And that happens every year. But this year, The jump was like 40% It was absolutely bizarre. And so I'm very excited about the program going to I excited to be going to med school in the neighborhood that I live in and be like really embedded in my community and excited to live somewhere for more than a year at a time. I've moved every year for the last 10 years. And this will be my first home that I signed a two year lease on this place. And that's like that feels like like root roots. So I'm very excited about that. And I'm nervous. I'm nervous that we are going to get slammed with another wave. I am nervous that I'm going to get another email asking for small, scrappy people who aren't afraid of the dark. I am nervous that it will feel routine by then. And I'm nervous that the goodwill that we relied on so heavily to save so many lives last year won't be present the second time around. I'm worried that people's wallets and hearts will be tapped out. If we have a surge the way that we did last summer and I don't want that to happen. And I am genuinely powerless. change whatever outcome is going to happen. I'm disappointed. I'm disappointed that people are so quick to forget. And I'm more disappointed that the CDC couldn't play strict parent just once, like, come on, you're the CDC, you could say things like, You do still have to wear your masks until we know what's up with this variant like they could have. They wanted to be the cool parent. And then they played, they were like, really cool. You can take your masks off, and I'm like, Oh, my God, first of all, half the country has been taking them out, stop anyways, so don't really know which kid you wanted to like you better, but I am. I'm like extremely stressed about that. And that's something that I think about a lot that the structures of mutual aid that became very robust during the height of things last summer, a lot of them have dwindled, rightfully, because there is less work to be done right now. But I'm like, This feels like right before the other shoe drops. And I hope that I'm wrong. But I'm, I'm very nervous. And I'm also just like, very pained looking at what's happening in India and Bangladesh, where my entire extended family is. And knowing that I can't help, like many of them, luckily, can stay inside. But if they get sick, there's no oxygen at the hospitals, there are no beds at the heart, there are no peep, there are no doctors, there's nothing, it is a deathtrap there, and I can't do anything. And I can't even send stuff because it would get stolen, or broken or take a month to get there. And all we can do is send money. But when you can't find the oxygen to buy all the money in the world won't help you. And so I'm, I'm we're all kind of like waiting to see what happens in Bangladesh and India and South Asia in general world, my whole family's just kind of like, how many family members will we have this time next year? We have fewer now than we did this time last year? And how many fewer is it going to be? And that's just like, I can't think about it too much. Or I feel completely desolate. I've been trying to focus on the things I can do. And the people that can help. But it feels awful that the people that I can help the least are like my family. And they're completely out of reach. So that's like, yeah.

Kit Heintzman 01:08:46

What are some of your desires or hopes or longings for longer term future?

Joya Ahmad 01:08:55