Item

Sid Azmi Oral History, 2022/07/20

Title (Dublin Core)

Sid Azmi Oral History, 2022/07/20

Description (Dublin Core)

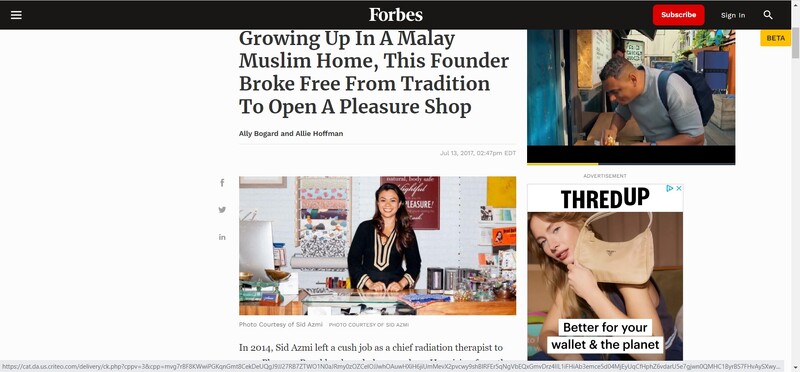

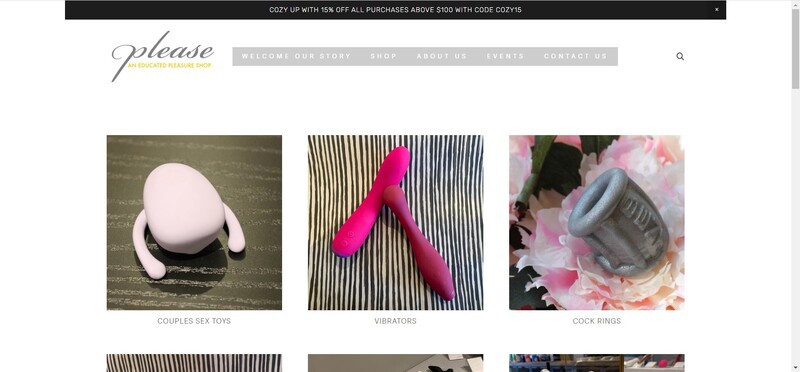

Self Description: "My name is Sid Azmi. I am an immigrant, foremost. First personally in in the United States. And now in France. I was highlighted for this interview, because of my work at a shop called Please. And I would like to talk a little bit about that. So Please, is a pleasure shop and I call it Please is a Pleasure shop in Brooklyn, New York. And I started it in 2014 as part of my work to normalize sexuality, while working with cancer patients in my work as a radiation therapist. And I'm a sex educator, I'm a hedonist. I'm a mother of three. I am. That's me."

Some of the things we discussed include:

Moving to the USA as an immigrant from Singapore.

Coming from a poor background to a place of financial stability and freedom.

Early childhood experiences impacting adult experiences.

Immigrating to France in early 2020 with son, while continuing to run the business in New York.

Being the small business owner of Please, a pleasure shop in Brooklyn, New York.

Store closing during lock down, transitioning to online sales, and reopening with shorter hours.

Inadequate small business support.

The the realities of unsafe working conditions and shipping delays of products in the sex toy industry.

Immigration borders between the USA and France throughout the pandemic; changing regulations.

Watching the news with son; stopping watching the news and being more selective about information consumption.

Homeschooling son; not having received any training to be a teacher; cultural values about education.

Giving birth to a daughter during the pandemic; changing hospital regulations.

Sex, hedonism, and partnership during the pandemic.

The 2016 election.

Watching from France what was happening in the USA under Trump; comparisons between France’s, the USA’s, and Singapore’s pandemic policies.

Changes in the US, transphobic policies, Roe v. Wade.

Free, accessible, and fast testing in France

France’s “Health Pass” in contrast to the American “Vaccination Card”.

Getting vaccinated as quickly as possible; friends taking a wait-and-see approach to possible adverse effects.

An astrologer having portended in 2019 a global big change coming in the spring of 2020.

How one talks about their own privileges and the privileges of others; shame, relief, and gratitude.

Different about death in Asian and Western countries; different cultural ideas about joy.

Staying in touch with loved ones in Singapore and the USA while living in lockdown; long distance emotional support.

Other cultural references: Marie Kondo

Moving to the USA as an immigrant from Singapore.

Coming from a poor background to a place of financial stability and freedom.

Early childhood experiences impacting adult experiences.

Immigrating to France in early 2020 with son, while continuing to run the business in New York.

Being the small business owner of Please, a pleasure shop in Brooklyn, New York.

Store closing during lock down, transitioning to online sales, and reopening with shorter hours.

Inadequate small business support.

The the realities of unsafe working conditions and shipping delays of products in the sex toy industry.

Immigration borders between the USA and France throughout the pandemic; changing regulations.

Watching the news with son; stopping watching the news and being more selective about information consumption.

Homeschooling son; not having received any training to be a teacher; cultural values about education.

Giving birth to a daughter during the pandemic; changing hospital regulations.

Sex, hedonism, and partnership during the pandemic.

The 2016 election.

Watching from France what was happening in the USA under Trump; comparisons between France’s, the USA’s, and Singapore’s pandemic policies.

Changes in the US, transphobic policies, Roe v. Wade.

Free, accessible, and fast testing in France

France’s “Health Pass” in contrast to the American “Vaccination Card”.

Getting vaccinated as quickly as possible; friends taking a wait-and-see approach to possible adverse effects.

An astrologer having portended in 2019 a global big change coming in the spring of 2020.

How one talks about their own privileges and the privileges of others; shame, relief, and gratitude.

Different about death in Asian and Western countries; different cultural ideas about joy.

Staying in touch with loved ones in Singapore and the USA while living in lockdown; long distance emotional support.

Other cultural references: Marie Kondo

Recording Date (Dublin Core)

July 20, 2022

Creator (Dublin Core)

Kit Heintzman

Sid Azmi

Contributor (Dublin Core)

Kit Heintzman

Link (Bibliographic Ontology)

Controlled Vocabulary (Dublin Core)

English

Biography

English

Community & Community Organizations

English

Consumer Culture (shopping, dining...)

English

Government Federal

English

Health & Wellness

English

Home & Family Life

English

Race & Ethnicity

English

Gender & Sexuality

English

Travel

Curator's Tags (Omeka Classic)

travel

immigrant

pregnant

embassy

family

Contributor's Tags (a true folksonomy) (Friend of a Friend)

abuse

Asian

Asian American

astrology

birthing

France

homeschooling

hospitals

immigration

Malay

motherhood

Muslim

New York

pregnancy

sex

sexuality

Singapore

testing

therapy

trauma

travel

Trump

vaccination

Collection (Dublin Core)

Asian & Pacific Islander Voices

Motherhood

LGBTQ+

Date Submitted (Dublin Core)

08/05/2022

Date Modified (Dublin Core)

04/18/2023

12/05/2024

Date Created (Dublin Core)

07/20/2022

Interviewer (Bibliographic Ontology)

Kit Heintzman

Interviewee (Bibliographic Ontology)

Sid Azmi

Location (Omeka Classic)

Pau

France

Format (Dublin Core)

Audio

Language (Dublin Core)

English

Duration (Omeka Classic)

01:20:24

abstract (Bibliographic Ontology)

Moving to the USA as an immigrant from Singapore. Coming from a poor background to a place of financial stability and freedom. Early childhood experiences impacting adult experiences. Immigrating to France in early 2020 with son, while continuing to run the business in New York. Being the small business owner of Please, a pleasure shop in Brooklyn, New York. Store closing during lock down, transitioning to online sales, and reopening with shorter hours. Inadequate small business support. The the realities of unsafe working conditions and shipping delays of products in the sex toy industry. Immigration borders between the USA and France throughout the pandemic; changing regulations. Watching the news with son; stopping watching the news and being more selective about information consumption. Homeschooling son; not having received any training to be a teacher; cultural values about education. Giving birth to a daughter during the pandemic; changing hospital regulations. Sex, hedonism, and partnership during the pandemic. The 2016 election. Watching from France what was happening in the USA under Trump; comparisons between France’s, the USA’s, and Singapore’s pandemic policies. Changes in the US, transphobic policies, Roe v. Wade. Free, accessible, and fast testing in France France’s “Health Pass” in contrast to the American “Vaccination Card”. Getting vaccinated as quickly as possible; friends taking a wait-and-see approach to possible adverse effects. An astrologer having portended in 2019 a global big change coming in the spring of 2020. How one talks about their own privileges and the privileges of others; shame, relief, and gratitude. Different about death in Asian and Western countries; different cultural ideas about joy. Staying in touch with loved ones in Singapore and the USA while living in lockdown; long distance emotional support.

Transcription (Omeka Classic)

Kit Heintzman 00:03

Hello, would you please start by stating your name, the date, the time and your location?

Sid Azmi 00:08

My name is Sid Azmi, and it is July 20. And I believe it is 14:07 in Port France, where I am.

Kit Heintzman 00:17

And the year is 2022.

Sid Azmi 00:20

Yes it is

Kit Heintzman 00:23

And do you consent to having this interview recorded, digitally uploaded and publicly released under Creative Commons License attribution noncommercial sharealike?

Sid Azmi 00:33

Yes, I do.

Kit Heintzman 00:35

Thank you so much. Would you please start by introducing yourself to anyone who might find themselves listening, what would you want them to know about you?

Sid Azmi 00:44

My name is Sid Azmi. I am an immigrant, foremost. First personally in in the United States. And now in France. I was highlighted for this interview, because of my work at a shop called Please. And I would like to talk a little bit about that. So Please, is a pleasure shop and I call it Please is a Pleasure shop in Brooklyn, New York. And I started it in 2014 as part of my work to normalize sexuality, while working with cancer patients in my work as a radiation therapist. And I'm a sex educator, I'm a hedonist. I'm a mother of three. I am. That's me.

Kit Heintzman 01:37

Tell me a story about your life during the pandemic.

Sid Azmi 01:42

It is an interesting, I guess, with a lot of people when the pandemic started happening in February 2019, I would say. No, February 2020. You know, I was just recently moved, I recently moved to France with with my son. And so we were sort of in this period of transitioning to our new life with French classes, French school system. And I also maintain my work in New York. And I was traveling back and forth to New York. And so there was a lot of back and forth, transitional things that were happening. So when COVID hit, you know, it was we were very much still in the movement of our two lives, that it didn't really hit us until the borders started closing down. And you know, the government saying like, you can't, you can't move. But also at that period, I was I was a few months, I was a few weeks pregnant. So part of me was also excited about being locked down, and not being called to do anything. And so it was it was it was a big change coming on to all of us.

Kit Heintzman 03:00

What were some of the things that you were thinking about when lockdown happened, especially in the context of immigration?

Sid Azmi 03:09

You know, I was very fortunate to be a American citizen, and then a resident in France at that time. So the borders closing wasn't really, you know, an issue for us, we could still move. So that I was I was, I was very fortunate about that. You know, I think in terms of immigration, you know, proxy, the flow of most importantly, my, my, my, my son's father to him was the thing that I was worried about in terms of immigration, and for my husband, who has a child in California. So that was the biggest immigration for me, per se, I was lucky enough to have access to both. Yes. And then and as COVID, you know, as COVID became more prevalent, and the rules started to change, you know, I, it was a it was a bit more of a hassle than anything that was truly seriously worrisome. Yea.

Kit Heintzman 04:10

Do you remember when you first heard about COVID-19?

Sid Azmi 04:14

Yes, I heard it from my mother in law. You know, who is who is French and old and older, sorry, and a little bit, you know, tend to be a little bit more excitable about things like that. And I'm like, Oh, come on, you know, there's like, 100 people in France who had COVID Like, what's the big deal in Asia, like, people die all the time. Like, you know, like, let's, let's not make a big deal about this. This is and you know, and she was telling us to wear mask and all that stuff. We were traveling in February and I'm like, like, don't worry about this. Like, it's gonna just pass so I Yeah. And yeah, that was my first memory from my mother in law.

Kit Heintzman 04:55

Was there a point where it started to feel more serious?

Sid Azmi 05:01

Yes, you know, when the when in France, there was a lot of public announcements where the President would come on TV and make a public statement. And he did this quite often. You know, and I think that's a little bit different from the states where you have your own state rules that govern and then you know, the federal, the President. Well, it was also Trump at that point. So, you know, it didn't have any real direction from from the from the American government. But in France, it felt more serious because the President was talking on TV, and there was this steps taken put in place. So I think, because the wave moved from Asia, Europe to the United States, so we kind of hit, you know, Europe got hit first before New York did. So. I know, I'm trying to remember pieces of this also, I know that the schools closed down, the schools was supposed to be shut down. And that mean that I have to be homeschooling my I had to homeschool my child, that was scary. And then that means that my business in New York that was somewhat going to be affected at some point. And on what level we didn't know, we were just going to move forward with with caution knowing that, okay, something big is happening. But I don't know what. Now, interestingly enough, I know this is totally not scientific or factual at all. I have on a personal level I have I, I speak to a spiritual astrologer who in October had said to me that Oh, sometime in the spring or early spring, the world is going to experience a major calibration. And so when it happened, I'm like, oh, was this a recalibration that this person had mentioned, and I do this astrology just to kind of line up my energies to the world. So it's not about you know, predicting the future. But it was kind of like, okay, there is something, there's a big change going on. And our job is just to ride the wave. So I kind of like was accepting it as it came on.

Kit Heintzman 06:58

What was it like watching what was happening in the US from France?

Sid Azmi 07:05

It was very sad. I felt I felt a lot of sadness. From the misinformation that was was was getting sent, the panic that people had, the denying reality is what it was, you know, and it's, it's, it was it was, it was, I mean, I already had a, you know, I already started do roman, the roman romanticizing my, my relationship with United States, I'm an American, and I moved to America when I was 19 years old, and America was everything I had dreamt about. And it was an incredible place to be. And I found the best pieces of myself in America. And, you know, when Trump came became President, that started to change for me, because I, I realized, you know, my closest friends were the same people who supported his values, who were against people like me, you know, and so I was starting already slowly, you know, kind of disengaging myself from being in the States. And then when I moved here, and I saw what was happening in the States, it was just like, Oh, my God, like, I can't believe this is there was a sense of relief on my end, okay, we got out at the right time. But But America was still my, my, my right, you know, and so and my business is there, and that's my big baby, and, and watching my friends sort of trying to find themselves amidst all of this misinformation and the frenzy that was surrounded because of the lack of leadership. That was very, I felt very sad. Yea

Kit Heintzman 08:41

What are some of the things you noticed about what was happening in France, especially at the beginning?

Sid Azmi 08:52

I would, I mean, I didn't notice, I mean, you know, your take, you're asking somebody who just moved to a different country. So I don't have a lot of relative comparisons to people I didn't know, I didn't have a committee that belonged to I didn't have a certain routine. You know, I didn't have friends, that many friends. But, you know, there was, there was, there was, to me, it seemed that there was a respect for what was happening, that we are there’s a some sort of a salad solidarity, that we are now hit with a national worldwide public health issue, and therefore, we're just going to put our assets where we're told to put it, you know, which was to stay home and be in confinement, you know, and there was a respect for the law. Nobody was when I when I had to do my grocery shopping for my family. There was nobody who was was, you know, had a problem with putting on masks. There was really a good sense of, we have to do this for everybody. And so that's what I felt like being here in France, and maybe that's just my foreign eyes not Knowing the ins and outs of language or body language or or whatever that was going on, but that's what I experienced.

Kit Heintzman 10:08

What's it been like homeschooling your son?

Sid Azmi 10:14

It was a nightmare. No, it was a learning experience and a nightmare. And I think it's healthy for parents to say, No, we are parents, we cannot love our children and also know how to be school teachers, I was not educated to learn to educate my child in that, in that perspective, in that sense, you know, and so it was challenging. And then I also have my Singaporean, you know, self, which is like, just do your homework, just do everything, just do what they tell you to do. Like, they give you X amount of work, you just do it. And my American son is like, you know, no, we do what we are, what we do what we're supposed to help us grow the most. And we'd get to define that for ourselves. Okay, the French system is like, a little bit of both, you know, so I was also trying to find this out for myself, you know, and I and my son really had an anxiety from having moved here from a different place, which is normal. People don't talk about this often, but it's normal. And so he was actually relieved to be home. And he was happy to be home. And part of me was happy that he was not unhappy. But I also felt pressured to continue his work. And it wasn't until I, you know, I kind of discussed this a lot with my therapist, who's French, but also has a background in dealing with immigrants, you know, and she said, Well, this is a transitional time for for all of you in so many levels. Who cares about school? Who cares about the schoolwork? You know, why not try to figure out a new norm, like, we don't know how this. So those words really resonated in me. And I just started to learn how to take a chill pill, you know, and so the first two weeks was rough, because I was just trying to make sense of this. And it's okay, because it's transitions always difficult for everybody, we all need to realize more how transition how stressful transitions are. But then after that, it was like, Okay, you're gonna do, you're gonna work, you know, we just set up certain rules for ourselves, but also left it to like a moment of just, we don't know. So we're just going to do what makes us happy. So we painted, we did Mary Kondo folding clothes, like religiously, that kind of stuff.

Kit Heintzman 12:26

How much do you think your son understood about what was happening with the pandemic?

Sid Azmi 12:35

I think he, I mean, as a child, he understood that, you know, I mean, biggest thing of all, he didn't have to go to school, right. But then also, we were reading a lot of articles, I was reading a lot of things in New York, I was I was I had to, we don't have a TV at home, but we have a projector where we will replay family shows. So the news was on all the time, so it was kind of like repeating quite a bit. And we had to stop that after a while because it was getting depressing. You know, and he, he, he, you know, he knew something big was happening. He was he was he felt even more when his father, you know, could not come in as freely and we had to write letters to the embassy, you know, stuff like that. So, that stuff he understood. I think when I talked about how much people had, how many people had died, how crazy it was for them who got separated, and then died alone in hospitals. He heard this, but I don't think he emotionally understood and rightfully so he's not he's not capable of that. But for my son, the pandemic was was a godsend. So in his own little way, and, yeah, that can be construed as selfish, privilege. It's okay. He was 12. It's alright.

Kit Heintzman 13:51

I'd love to hear more about the process of petitioning the embassy for your son's father to be able to come in.

Sid Azmi 14:00

Right, so I'm trying to remember how that how that all went on, there was certain rules that you know, you had to you couldn't travel if you were a resident. So basically, France sets up different different. And all of these processes were ever changing. So every two weeks, there were new things. We all know this. But you know, it became like, Okay, you can't enter you can only enter if you're a resident, you can only enter if you were a citizen, you can only enter if you were, you know, different roles and stuff. And then they started adding on if you had a child in custody, if you had if you had a family member or child living over there, and it had to be because of like, you know, need or something. So there were all these things that we had to prepare for the embassy. We had to give paperwork of our paperwork being here in France. You know, if he were to get sick, would we be able to cover him so we had to get health insurance for him. And then we had to have the dates and I don't remember if there was testing at that time, I don't think that there was testing in the very beginning of things. I really don't remember because we've gotten tested so many times in different ways. But you know, and the embassy was, of course, overwhelmed. So you had to kind of keep writing letters. But then they also didn't know what the heck they were doing. So do you buy your ticket before you get a letter? You know, do and we found out later on that the embassy would only entertain letters, people who already had a ticket. So these are the you know, and we were privileged because we could, we had the luxury of being able to plan this stuff out and change our plans, financially and also logistically, yeah. So I recognize that.

Kit Heintzman 15:47

Was he eventually able to come?

Sid Azmi 15:50

Yes, yes. I think he came in for Christmas. He came in for Christmas 2020. That was the first time that he came in. I don't remember us. I don't think we left for the States. No, we actually went to the States in summer 2020. Yes, when the confinement was lifted in the beginning of this late summer, no, beginning of the summer, sorry, beginning late June. So we could travel out and we could come back in, but he could not enter till the end of December. And, and yeah, he managed to enter, yes.

Kit Heintzman 16:32

What does it feel like to travel in summer 2020?

Sid Azmi 16:40

I mean, first of all, it was very strange for someone who did like 19, like round trips in Paris, New York, certain years, you know, the environment around travel was definitely not the same. It was nice, because it was quieter, and, I didn't, you know, and then but it was also like, wow, like, I remember I have a, I have a post that says, This is what privilege looks like, you know, taking a picture of my plane window. And, you know, being among the few who could who could do this freely, it was really a humbling like, moment. Like, you know, we didn't have we didn't, we didn't need to be anywhere other than where we were. And we didn't have anybody who we were dying to see you who are in a dire place. So we were really, really lucky. And despite all this, we were the ones who had the permission to do what we want. So there was some shame in that great relief, you know, but also, a lot of gratefulness. Right. And I think for me, because I was pregnant at that time, you know, and taking my son to the states to be with his father that summer, and also meeting my parents so that my parents could see their daughter pregnant, was was was something wonderful. It was a very short exchange, but wonderful.

Kit Heintzman 18:04

Would you share something about that relationship between privilege and shame that you're expressing?

Sid Azmi 18:10

Yes. You know, I am still trying to articulate this Well, and, you know, coming from a place where I grew up very poor, I clean houses as a child, you know, and I get to do anything I would like to do. And I'm not saying anything glamorous, you know, I have no big aspirations like that I don't need I'm not into wealth or big things like that, but the freedom to do whatever my heart wants, I can set that in place. And, you know, the, so I'm very proud to be that, but also I guess, for me, that's for me, you know, in some ways, I can make more sense out of it, because I somewhat earned it. So that privilege. I know, I earned I earned that privilege. But for someone like my child who was born into this situation, you know, there is a big part of me that it's quite uncomfortable with that, you know, when my child takes the plane and say, Oh, great, you know, like, nobody in this place. Like, at least we get rid of the stupid people. You know, I'm like, don't say that, because your mother was one of those stupid people. And, and this is where the shame comes in. When I'm thinking like, what, when in my education, in my parenting, my child Did I did I did, I missed out on this, but, you know, all of these experiences has to be learned. And, you know, gratitude, shame, privilege. These are all things that come in comparison with with with the other with the opposite. So in his life, he's going to learn this thing and I need to just absolve myself somewhat of like, okay, I can only educate so much. I can show you different experiences. But I also know that in his own little way, you know, having his dad on the other side of the other of the world is already something a privilege he didn't, doesn't have. So, as glamorous as his life might seem, you know, there's also some deep pain that he has to endure. So, yes. I would like to find a better word for, for shame. Because it's not exactly how I feel. But I have yet to find it.

Kit Heintzman 20:35

What was it like when your son first got to see his dad that summer?

Sid Azmi 20:42

I mean, he was he was, he was happy. He was glad you know. I think Is it his mind, I mean, he, he never He never. I don't think he really understood like, there was a possibility that he could not see his dad for a while. Right. And so you know, he, he, yeah, I don't think he really registered how, how, how dramatic the situation was. So he was just glad to see dad. And we're gonna go to Wingstop and eat a bunch of wings and just like, junk out and Mom's not here, you know? Ordinary 13 year old like, yeah, reaction 12.

Kit Heintzman 21:31

What was it like for you to get to see your parents with that awareness about how precarious travel was?

Sid Azmi 21:41

You know, I was I was, I was glad to see them. You know, but when does this [inaudible] travel was, you know, from my parent's perspective, anything I did was already precarious. I was a girl who left home from Singapore. So like her taking the plane during COVID, with her kids being pregnant. I mean, she was already out of a mind when she was like, 18. So this is just, this is just being her. Like, if she were to drop that tomorrow, okay, we kind of expected it. So they don't they kind of like, have this sort of mentality with me. You know, and I've had friends actually, who told me like, God, how many times did you travel from New York to Paris, like, during the pandemic, and we traveled a lot. And they were like, God, with all the hassle and the immigration and the testing, like, how did you manage that like, and I'm, like, we just learned to kind of roll with the flow, you know, if we want it to go to the States, okay, we said, we want it to go to states, we just have to do things like, like what everybody has to do, and whatever the, you know, consequences or surprises that come along the way, you just have to roll with it. I think that is that is a big thing that most people had to learn during COVID How to just roll with surprises. I don't know.

Kit Heintzman 23:02

When was access to testing like for you?

Sid Azmi 23:06

So in France, it was very accessible. So you could get a test testing was free. First of all, testing was free and ready in 24 hours. And then as vaccinations came on, you know, they they regulated it to make it only free for people who were vaccinated and because of because of all the different, you know, systems that were set in place about being in public and stuff like that. So there was some, you know, politicized politicized a politicization that happened with that too. But it was free. So it was it was readily accessible to all of us.

Kit Heintzman 23:50

What are some of the things you noticed about the conversations about vaccination in France?

Sid Azmi 24:03

I'm trying to remember this. Okay. So you know, there was I mean, there's so many same that same thing in states you know, there's like always a conspiracy theory about oh, vaccination is just the government's way of like following you around or whatever not or making you do something you don't want to do. And then in France, you know, they didn't want to call it pro vaccination. So they call it like, they had a health pass that you know, it's the state's you just had to show a vaccination card in the state in the in France, it's kind of showing your vaccination card, but it's showing your health pass, which is like calling it something else, to move it away from government telling you to get vaccinated. So if you so you can get the health pass and you could go out to eat in public or attend shows, you know, if you've been vaccinated and properly vaccinated, or you get tested 14 hours before attending such things. So people were getting tested during the weekend, left and right. So they could go eat, you know, at the restaurant before that. And, you know, so I've always believed in vaccination, I got my myself vaccinated, you know, my child was vaccinated as soon as he could. And I think he even went, we even took him vaccinate in the States, because it was open to him earlier than in France. And then suddenly, when we were inviting people out, and we realized that some people were not vaccinated, because they wanted to wait for other people to get vaccinated to see if like, this was some sort of a scam. I got upset about that, you know, and it was interesting to kind of like, okay, so we do have friends amongst us who don't believe in this, you know, and we actually disinvited two friends from coming to our house because they wanted to wait, you know, if vaccination was was correct or not, and I'm like, my son is vaccinated if I put my son on the chopping block, you know, and you're still waiting to see if it's going to hurt you or not, that's not cool. So you don't have to come. So but but same same conspiracy theory, same, you know, opposition towards getting vaccinated as the states, but the misinformation was much lesser.

Kit Heintzman 26:20

When the friend was uninvited, how did they react?

Sid Azmi 26:26

Um, you know, I didn't, I didn't really pay too much attention to it. I just said, you know, I just told them this. I mean, I just, I didn't we didn't make a drama about it. It was just like, okay, you know, like, that's fine. We'll see each other some of the time full stop. I don't want to make a drama about it. I don't want to impose my views on you. I mean, I didn't say like, I didn't tell them. Like, the way I said it to you. It was more like this is the reason why we get vaccinated is because we're a traveling family, we have obligations internationally. And we would like to honor them. And it's important to us that we're around, but we're surrounded by people who are vaccinated because of because of the lives we try to uphold. This is what I said, Yes. And then that was a way of saying, Okay, you're not, you can't come. So they just didn't come. They just they just said, Okay, well find out the plans.

Kit Heintzman 27:16

What was it like trying to find friends and build community in a new country during the pandemic?

Sid Azmi 27:30

Um, you know, I think from I mean, I've always maintained my community. Oh, pardon me. Pardon me? Sorry. Can you hear me? Okay. I've always maintained my community in New York, and in Singapore, and having all the time being confined, you know, we really just talk to each other on the phone a lot. We call each other often. And so it was a really nice moment where everybody had nothing else to do, but to maintain contact with each other. And also, I guess, this is why I didn't feel so terrible, because like, you know, you could you we had FaceTime, we had WhatsApp, video calls, and zoom and all that stuff. Making new friends was, of course more difficult, but it was alright for me, because I'm always slow to making new friends. I'm someone who needs to find myself first and find my bearings before I reach out to others. So it was perfectly timed, in a sense.

Kit Heintzman 28:33

What did you notice about what was happening in Singapore related to the pandemic?

Sid Azmi 28:40

So Singapore had a very totalitarian approach to you know, like confined, can't go out. Borders completely locked. You know, but because I wasn't flowing, you know, to new to Singapore, it wasn't a big deal. My best friend works as a nurse. And so she kept on working. I think more more so it was for my aunt who lived in an island off of Singapore, which is Indonesian, you know, it was harder for her because she lived on an island and she and her income was dependent on tourists that came in. So she had no work. And she was caught at home with a very ill husband, you know, who had pneumonia. And so, you know, all that stuff was a lot more real for a lot more scarier for her than for like any of us. But Singapore, Asia did take on a much more totalitarian approach. You can't even leave your house. So I imagine that must have been tough, very tough.

Kit Heintzman 29:44

I want to go back to something you introduced in the introduction, which was hedonism. What's that been like?

Sid Azmi 29:53

What's that been like during the pandemic? I was pregnant during that time and my body, I was I was pregnant with it with a daughter and my body loved my husband. And I was just in a state of pure lust for my partner. And so we had a lot of sex. And with nothing else to do, we consumed books, we consumed each other, we consume the food that we could consume, we really consumed each other, like the family in a sense. So it was quite, it was really pleasurable on my end, because, you know, I had to, I was told you can't do anything. So for Type A, that was, that was awful. But there was also permission to just be, which was great. So I took walks, long, long, two hour walks, I took naps, I fucked when I wanted to, you know, my kid was at home happy as a clam. And we were just, we were just in, in, in bliss, really. When we didn't, when we didn't connect with the world. And we were lucky, we were lucky, because we had space, this is something to be said, we had a we had a much bigger apartment than we did in New York, and everybody had their own rooms. So it was nice that we can engage with each other and then also take our space. You know, in France, you could go out for like five kilometers and take a walk with a piece of paper, it's fine. But you still could You could still go out and like not be with with people 24/7.

Kit Heintzman 31:33

Over the course of the pandemic, did you need any kind of routine health care related to the pregnancy?

Sid Azmi 31:39

Yes, yes, I did. You know, and I remember that I couldn't the first time that I had my ultrasound, to look at the baby, my husband could not come to the hospital, because it was just the mom. And so, you know, we could we could just video chat, the the moment of like, oh, you know, this is your baby. And, you know, I spoke to some other friends who were pregnant at that time, you know, and they were like, very sad about this moment. But I guess having had having an older child, I'm like, there are just so many moments in your child's life, where it could be a really significant moment that you really won't remember. So we're gonna be alright, if you didn't see the first ultrasound, we're going to be alright.

Kit Heintzman 32:27

And what was the experience of giving birth like?

Sid Azmi 32:30

So in my, in my instance, I, you know, my, my due date happened to fall at the time where fathers could enter the birthing room and stay, my friend who had who delivered I think six weeks before her husband could come in, but he could not leave at all. And he was a smoker. And it was really like stressful for the family at the beginning. And then some before that, you you had to go in on your own. So I was really lucky that I could, I could my partner could come with me. Of course, we had to be really careful with the mask and all that stuff. But that was fine. We got used to that. And then I guess the biggest the biggest moment was, you know, you could have one visitor only. And it was between my mother in law and my son. And my wise mother in law said it should be my son who should go see his sister who should be the only visitor, you know. And so that was nice, because it was it was someone else, maybe they would they would not have the same grace. Yes. So my mother in law didn't see my daughter until like a week later, which was fine. Yeah.

Kit Heintzman 33:42

And your mother in law lives in France, right?

Sid Azmi 33:44

Correct. Correct. And now, interestingly enough, so my husband's grandmother died at the age of 100, a week before my daughter was born. And so, throughout the whole confinement, my mother in law had went to stay with her because obviously, she was fragile. And because she was staying at home, she had visiting nurses who would come in all the time to take care. So it was really, really scary for her to get COVID, you know, to the you know, for my mother in law. Now, for me, you know, I guess this is a bit different. I, I'm coming, I'm coming from Asia, and our relationship with death is very different from from the Western idea. And to me, it's like, okay, you're going if it's your time, you're going to die of something. So it could be COVID. It could be whatever, you could take precautions, but we're not going to take precautions to the point where we're not going to live. You know, so when I was listening to my mother in law, being so frantic about things, part of me is like, okay, take a chill pill, you know, but she has her own ideas and beliefs and associations about death and all that stuff. So she was very, very careful about COVID and being with her mother. And maybe I would be too if if I don't know if so if I if I had the relationship with someone like that, I'm not sure. But you know, that was that was that component of it. Sorry I digress, did I digressed?

Kit Heintzman 35:17

You can't digress in an oral history interview, it's all it's all perfect.

Sid Azmi 35:21

Okay, thank you.

Kit Heintzman 35:24

Would you give me an example of a moment that really felt like living during the pandemic?

Sid Azmi 35:38

That really felt like living define, like,

Kit Heintzman 35:42

So you had said, I don't want to stop, like, I'm not gonna stop living because of this. So what's, what's something that that gave you permission?

Sid Azmi 35:52

Okay, I guess, you know, live living living in a sense is like making, you know, fearing that something bad is going to happen, I'm not going to go out and, you know, do the things that I want to do. So for example, my mother in law was very hesitant to do, you know, marketing, you know, and it was sort of eating like the same thing every week, because she didn't want to go to the marketplace, because she was worried that she would catch COVID and stuff like that. And I just thought, Okay, that was a little bit too much, because her mother wanted to eat some of the meat, like some specialty things. So it was just like, there was this sort of, you know, go back and forth between them, you know, and for me, like, you know, I was pregnant and my mother in law's always like, Okay, you gotta be careful, you gotta be careful, you gotta be careful, you're pregnant, you know, and you live with other people. And I'm like, Okay, I'm, I'm going to the market, because I need my time alone, it's my excuse to just be on my own. I also like to interact, just seeing other people around on the streets, you know, I want to be in a place where this is normal for me, you know, being in a supermarket and not being at home. And so I'm going to do that do taking the precautions as best as I can. Because Because that's just what I want to do, what to me feels right to do. And just because I'm worried about, you know, catching COVID, I'm not going to stay home and not do these things that I enjoy, you know, and I understand how that can be responsible, in some ways of it's, you know, it's so many levels. But I think in my context, the risk that we're taking one that bigger, right?

Kit Heintzman 37:30

What was happening with Please, back in the US?

Sid Azmi 37:33

We're so pleased with please, you know, I guess, very quickly, France, Europe had gone into confinement, and very quickly, like, the more progressive states were sort of taking the same measures, right. So New York was saying, Okay, we're going to be confined, nobody's going to go out. And then like non essential businesses are closed. And of course, there was all this frenzy about what hell is a non essential business. And being a mom and pop store, like everybody wants to get non essential business because we need it to pay rent, we need it to survive, you know? And so no, we're not a, we're not an essential business. We have to close down, you know, and it was very scary, because that's, that's my livelihood. You know, and the business survives, because we continue business. And if you stopped business for like, a couple of days, even, you know, people stopped coming. So can you imagine what, what, what a pandemic, might do to your business? Its going to kill it. So and it was very scary, because I couldn't be there. But even if I were there, I couldn't do anything about it. So those were the things that were going in my head, like, what I could have done more being there. You know, it was a learning, it was a learning moment for me to say, okay, you know what, just because you're there doesn't mean things can happen. The universe really told everybody to just come down and just stay put. So I figured out ways to still run my business, do online businesses hire one person to come in a week, you know, to just ship out orders. And just make little make little businesses and just and really accepted the fact that nothing was moving for anybody, you know, Dean and DeLuca closed on Broadway Street in New York. If they can close, any of us can close. And the fact that I'm still here, and maybe those weeks, I make 60 bucks a week, it's fine. It's fine. You know, so that was also just letting go of what was going to happen the next month whether I was going to be able to pay my rent or whatever. I'm just going to do my best. I talked about things with my landlord if he was, you know, I told him listen, I can't, I can't squeeze water out of a stone. Okay, so what I have I give you I give you the best I can just so you know that I'm trying to keep up my end. But this is just what it is. And you know, yeah, and since that, you know, I've paid him back the times, but it was hard but because there were no regulations in New York that says, okay, you don't have to pay rent, you don't have to pay your sales taxes, you know? Nothing, nothing was in place for small businesses.

Kit Heintzman 40:13

What was it like communicating with your employees about it?

Sid Azmi 40:23

So, you know, I, I think everybody knew that this was I mean, this was going to happen with everybody, you know. And there were actually luckily for me, also, my staff happened to be students, and a lot of them just said, you know, we're not going to stay in New York, we're going to go home to our parents, so we actually can't work. So that was good, because I didn't have to keep people in employment, you know, when I couldn't afford to do that, right. And so I only hired somebody who lived close by who could come in and just run this orders for, you know, and I paid, I definitely increased payroll for the for the staff full staff. And then when we could open when, when, when New York reopened, I think New York just basically reopened. i Sorry, I live in two timezone. So I'm trying to remember how it happened. But I think the store could open all the time, I decided that I was just going to open shorter periods, and pay my staff more. So that way, they wouldn't lose their income working, you know, less. But at the same time, it was my way of also like, you know, what, fuck capitalism, if people wants to buy from us, you know, they've survived three months without being able to buy shit, like, now it's open, they should be able to come where it's convenient for both them and like the people working for the community. So these are my hours, I paid my staff more. And we made more sales we made we made we made more sales than we did before the pandemic. And I don't, and we'll talk about this little bit later. I don't think it's got anything to do with the pandemic, I think people were just happy being out and about shopping. But that model of like, you know, not being open all the time is what Americans, like capitals, kept the capitalism like, wants to tell people I was really happy I did that.

Kit Heintzman 42:19

Can I invite the conversation now about the idea that people were having more sex during the pandemic, or that sex shops were exploding with business?

Sid Azmi 42:31

Oh, sure. You can totally invite it. What do you call that? Yeah. So there was an article that was a New York Times article, there was a journalist who was talking about this, and he interviewed me about about this. And, you know, he said, Oh, sex toys, or the sale of sex toys are really going up. And what do you think of that? And I'm like, No, it's not. And I'll tell you why. It's, I mean, I, I don't have the customers coming for it. And and the thing is, they're on so many levels, like, I'll tell you why business is not it's not exploding. We can't get goods, because all of the shipping are delayed from Asia, for example, manufacturer, like companies are like, on hold. But also the psychology of sexuality is that people feel more aroused or desire happens in a place where people are, are calm and joyful, and happy, you know, and the pandemic was not that. I mean, yes, we had more time being at home doing nothing, you know, we had the permission to do nothing. But if you live in New York City, in your small apartment, and your rent is really expensive, nobody was not worried about if they're going to make rent next year, or next month, you know. And then if you are a couple, the kids at home with everybody being at home with the stresses of homeschooling with seeing your partner in the same pajamas every day, like, there was no way like that could feel sexy. So I think in the beginning part, in the beginning part of the pandemic, people might feel like, Oh, my God, this is great. This is like a holiday imposed on all of us. And we were all giddy with this new change. But as in all novelty, things are fun in the very beginning. And then real transition hits in, you know, and then reality becomes a bit more everyday like, so sex becomes more everyday like, you know, so I don't, I don't I think people had the opportunity to be more curious about their sexuality. And yes, maybe there was a little bit of a growth or a continuous there was there was interest in sex toys, but whether it was booming, you know, like cat food on sale? I'm not sure. I don't think so. I really don't think so.

Kit Heintzman 44:49

I’mm curious other than the pandemic, what have been some of the social and political issues that have been on your mind over the last couple of years?

Sid Azmi 45:07

I think I've spent like the last few months just trying to not think about the things in the States, right? And it's just it's just, it's just so disappointing to see how immigration unfolds in even in France too. Don't get me wrong, anywhere you go, there's always going to be this sort of blame it on the immigrants, you know, and I guess for me, you know, immigration is always a very big thing. The thing is, when I moved to the States, you know, I never saw myself as an immigrant. You know, I always saw myself as everybody else, I was trying hard as everybody else. And I didn't get jobs, I couldn't work jobs that, you know, being an international student, you know, the jobs that white kids didn't, didn't want black kids didn't want pink kids. And when I got those, those jobs, you know, so to me, it was just like, Okay, we just gotta work your way up, you know, and I but I never even I never even looked at this as like, I'm somewhat different. And it became more and more clear as I got older, and and now that I have my son, you know, in France, and you know, the difference in our skin colors. I'm noticing this more and I guess language is also a very big thing, because Singaporean speaks English, and when I moved to the States, I was already fluent, I could communicate freely. And when I was in France, you know, not being able to speak, not even tell a joke, like on the street was really bothersome for me. So like, and living through to the experience, you know, with my child is really hard to see how difficult it is for someone to integrate, you know, and, and it was on its Yes, so immigration was always big on my mind, and seeing how this is how the world has become a lot more. I don't know, free, but also so secular, so segregated like that. It's just really disappointing to me, and everybody, everybody does this. So it's not just Americans, French, Asians, we all do this. It's just why, you know, and then yeah, I guess, you know, in the States, you know, when when Trump became president, like, you know, him revoking all the things about transgenders being in the Army, and all the different things that he revoked, it was just terrible. And now we have Roe versus Wade, it's not even go into that, because it's just, it's just so scary. How do you feel about being in the States right now, are you terrified?

Kit Heintzman 47:52

I'm also an immigrant. And I don't, I am, I am very grateful for the freedom to choose to be here and the access to leave when I so choose.

Sid Azmi 48:08

Yeah. Yeah.

Kit Heintzman 48:12

I'm curious, what does the word health mean to you?

Sid Azmi 48:20

I guess being, mental health is a big thing. Mental health is a big thing. And having access to being able to take care of your body, your mind when you need it to when you're feeling scared, that it's not working is is, is its lifeline, it's really important. Really, really important. And it shouldn't be a privilege, it should be access for all. And I am very saddened when I think about people in the states not being able to get the care they need, you know, and how expensive things are when it doesn't have to be that way. Coming from Singapore and being in France and having like nationalized health care, like it's, it's longer, but everybody has it, everybody pays for it. Everybody pays for it for each other, you know, and I don't understand why America can't get there.

Kit Heintzman 49:27

What are some of the things that you'd like for your own health?

Sid Azmi 49:32

Well, I would like to be a bit more fit so I could run around my children and not have to gasp for air. I feel very grateful for the things that for my health. You know, I'm very grateful for the fact that I get mental health support. You know, and I would like for more people to talk about this. I see a therapist every week. And I, whether I have something to fix or not, is not the, it's not the goal of therapy is just to be processed, I enjoy being able to process my thoughts and to be able to talk about it and to be able to rethink what I think is really a wonderful, wonderful thing to have. Because self-awareness is so important. And you know, it just we don't want to be people just living through life, live driving through you, you know, you want to be the one driving through your life and making decisions for yourself and being able to look at it says, Yes, I did that I did that. It's like, oh, instead of oh, I don't know how that happened to me. I had lunch with a friend today. And she says, Oh, you know, sometimes you can't control what you say. And I said, Yes, you can. And she looked at me, she goes, What do you mean, sometimes you just say things like, since it is yes, but in that event, so intentional. so, so important, that comes from mental health, and I'm grateful that I get access to it. And I think it's something that everybody should be more aware about.

Kit Heintzman 51:14

What does the word safety mean to you?

Sid Azmi 51:32

It means a lot of different things for me. For me, you know, growing up in a household where I was sexually abused. You know, being comfortable in my own home is a concept that I am still learning. I locked my door. Every day, every moment my house door is locked before I go to bed, I check my door because I'm always terrified, someone's going to surprise me when you know, I, when I'm lying next to my partner, that is when my mind my body feels at home when it feels safe, when nothing can hurt me when I really go to sleep, rested, like fully asleep. And without that even at the age that I am, you having been through the things I've been through. I don't I don't sleep well, because I don't feel safe. So there's that safety in terms of very innate deep sense of, you know, me and the world and this financial safety you know, which again as an immigrant is a scary thing, because when you leave all of your stuff behind and you come with nothing and you know, that looks in different ways that looks different ways for different people, you know, I when I left home I was 19 so I didn't have to give up a lot and I was happy to not bring like you know, I didn't have any furniture it's it's it's it's it's really a de-shedding it's like a snake losing its skin you know, it's really sort of the de-shedding that happens to yourself that you have to come to terms with and telling yourself that okay, whatever new adventure that you're going to come on you're gonna you're going to it's going to make it you're going to find something new you're going to be just fine so that is a that is a safe that's i don't know i If you want to be more specific you can ask me more specific questions because that means a lot of different things for me.

Kit Heintzman 53:43

Again, your answers perfect exactly as it is

Sid Azmi 53:47

When you know and I could think about safety sometimes you know I worry about my shock I worry about my not being able to take care of it and run to it when something happens you know? But you know life life life sometimes unpleasant surprises you unpleasantly sometimes so our our.

Sid Azmi 54:17

Okay, yes, I don't know what happened. Okay, so safety, you know, I guess our perception what we think of, there's no guarantees in life, right? So like, you know, at any moment of time you think you're safe. And now, it might not be the case actually. I mean, this could take an interesting flow, because, you know, I grew up in a culture where you have to suffer in order to feel joy. So whenever I used to feel so much joy whenever I was smiling, my mother would say, Why are you smiling all the time? Because I'm happy. This is she says to me you're happier, that means God doesn't love you. Don't be so happy because you might things might get taken away from you. And so growing up, I always had this fear of like, okay, if I didn't work hard enough, if I didn't take care of things well enough, if I didn't do the day to day now, then it might just end on me. So my relationship with safety, I don't I don't feel safe most of the time. Yes, it's really a state of mine that I have to kind of like actively put myself into.

Kit Heintzman 55:33

What are some of the things that you're teaching your children about safety as well as just happiness?

Sid Azmi 55:44

I want to be I'm proud to say that we have a happy household. From the beginning of the day to the end of the day, you know, nobody wakes up upset. We know we're not the type people who wakes up angry. There's always the radio playing with the news as always the coffee machine. Good morning. Did you sleep well last night? Did you have good dreams? These are the these are the questions we ask every single day, very different from my upbringing. So already, I think that my children welcomes the day in a nice way. You know, this kisses is hugs. And, you know, it's a new day, it's, it's an it's a new opportunity. And I don't want to say this, like, okay, it's a new day. So we have to do new things. So we have to experience new things. It's just another opportunity for us to feel the things that we want to feel, you know, maybe there's some leftovers from yesterday that we were unhappy about, okay, now that we've had some rest, maybe we can talk about it, and find a way to somewhat think about this more joyfully. But, you know, I, I've had conversations with my oldest son, and now that he's older, you know, we don't want to we, before I used to tell him, like, don't work hard work smart. You know, now I tell him, you know, just do it, just do it. Just do it. Because just do it joyfully. You know, do it, do it, because you find it interesting. And it's a bit hard, because I mean, talk about a teenager doing his homework, it's like, there's nothing joyful about homework, right? And then the other day, he said to me, you know, now when I do my homework, and I don't want to do it, I say to myself, you know, there are other people who don't even get to do homework. So I'm just gonna, like, make this fun for myself, you know, it's simple common for a 13 year old, but very deep, I think. So we do that. And in our little arguments, you know, we fight all the time, we can scream each other all the time. And we have, we have a word restart, when we when we say, OK, restart, you know, that means we let go of whatever that's past, and we move on. And because we've done this so many times, we know that we can get mad at each other. And it's not, it doesn't linger. Of course, times, you know, we say hurtful, more hurtful things that need to get talked about, we talked about it. But, you know, I, I think the beginning of the day is really important. It sets the tone of how the day is like, you know, and and there's no expectation of what you have to do for the day, other than just like, well, welcome the day, whatever the day brings, to start.

Kit Heintzman 58:25

How do you feel about narratives of the pandemic as a moment of trauma? So when people say things, like the pandemic was a moment of trauma for everyone, or the pandemic is, how do you feel about it?

Sid Azmi 58:37

Well, I'm kind of irritated by it. Because, you know, whenever someone has a generalized, you know, statement about something so big and they put such a strong word trauma, trauma is a huge word, you know, and it's, it's, it's, it's been used so frequently in today's context that like, you know, I took the bus, someone rude was rude to me. And that was a traumatic experience, like, whoa, wait a second, like, since when, you know, this term, so freely used so I, I, I'm irritated by that. And I don't want people to I hope that people don't, I wish more or less people would would put it in that way. But it also when you put such strong and such energize words and things like that, and trauma has so many like emotions attached to it, right, like shame, like, feeling guilty, you know, someone else seeing somebody being traumatized, they're feeling guilty, they feeling bad, that that other person won't want to share if something good actually happened to them during the pandemic, you know, and we are getting into this culture where it's shaped to suck, and I don't want I don't want to be part of that. I'm sorry, you know, and for every bad thing that happened in life, there's something good that happened in place of it and for humanity to keep going and for us to keep evolving. We need both. We need to hear both. So, you know, I, Yeah, my short answer is I'm irritated by it.

Kit Heintzman 1:00:10

I'm curious, how are you feeling about the immediate future?

Sid Azmi 1:00:17

I don't, I feel great, I feel very excited about it, I feel very happy about life. And that's the thing, you know, you, you don't know what's going to happen next week, two weeks time itself is already a very complex thing to wrap your mind around. Because it's, you know, it could be a short time, long time, a long time could feel like a short time. And it's really your perspective, that changes, you know, how all of your experiences during the future the present next week, you know, so I don't, I don't tend to think too much about the future, I just, you know, I have plans that I have in place about my to-dos, you know, appointments and stuff like that. But I really try and live in the moment I and then it's difficult to do that, especially when you have kids, especially when you have to be responsible for people. But it would be very, very sad. If I was so terrified about the future that I didn't take the time to have an ice cream with my child, I would feel so sad that my child would have that kind of story to tell.

Kit Heintzman 1:01:32

What are some of your hopes for a longer term future?

Sid Azmi 1:01:48

I wish that the world would be more accepting of one another, you know, and our not say welcoming or like, I guess with the whole political, it's so charged, it's so segregated, you know, in, in our own values and belief systems and all that stuff that I wish that we I hope that we would just be a lot more open to experience another, you know, and in the conversations that you have with something else with someone else, you're bound, you're bound to have like a like, oh, like, I don't know, you know, and in a moment of acceptance, you know, and with that happening, I, I guess for me, like I've worked in, you know, I've worked in sexuality, where, you know, there's a lot of taboo around it. There's a lot of taboo, being an immigrant, there's a lot of taboo, being a Malay Muslim woman immigrating, having non converting their partners, you know, and all that stuff. And it's just like, I wish people were more interested in my story, rather than upholding what is right for them. You know, I would like for us to just experience instead of being right, who cares about being right? Who cares about what you believe in? You know? Yeah, there's just so much lost when we don't when we're not curious.

Kit Heintzman 1:03:32

Who's been supportive of you, during the last couple of years?

Sid Azmi 1:03:38

Me. And that's very important. And that is not a, you know, I'm into myself mode, it's you, you are your best advocate and you can take care of yourself. And your body remembers and your mind remembers the past generations, like actions and values and skills, so you will have a lot to offer yourself. So I've been supportive of myself. My, my partner has been supportive of my of me, My children, you know, even even in this small ways, you know, even when I remember when my son first entered my shop, and he's like, What is this? And I'm like, it's a body shop, you know, and he's like, oh, okay, there's a penis. Yes, it's a body shop. Okay. And he started telling his friends, it's a body shop and actually all of it became like a parent. The parent teacher association started calling Please a body shop because they started to hurt kids calling it a body shop. So that in itself is is a big win for me because that was what I was trying to do for the community was to educate. I have my aunt who is one generation copy, I have a copy of her. She moved from Singapore to it to Scotland and and back You know, and just having this intergenerational immigration sort of person to compare your stories to is great. And then my best friend in Singapore and I would say on some level my parents.

Kit Heintzman 1:05:15

Could you give an example of a moment in a pandemic where you needed support and then received it from one of these people?

Sid Azmi 1:05:31

Okay, so if you if I was talking about a moment that was stressful during the pandemic, right, I would say for me, probably it was during it was two things. Okay. Number one, it was business. So being in a business in New York, and I would say my very good friend, Sheila, who owns the first Brooklyn lesbian brought bar in first lesbian bar in Brooklyn was was my big source of communication. And, you know, just talking to another business woman, business owner, and being able to bounce ideas and just being able to say, okay, just calm down, just slow down. We're all in this together, you know, where if it's going to go to shit, I'm gonna go to shit, you're gonna go to shit, it doesn't matter. Like, it's okay. Everything that we've built, all the money we've put in is going to disappear in a while. It's okay. Like, you know, what you've got, we just reminded each other of like, where we were, you know, and that was that was that was that was, that was great. I mean, that was, that was what I needed to hear, you know, because you couldn't fix anything. During the pandemic, you couldn't save anything, you couldn't move anything. You couldn't get people to buy, you, even if you invested all the money, you couldn't do anything it was, it was something that's somewhat great about that experience. Because you realize sometimes that you realize that life really has its own rhythm. And your job is to meet that rhythm. It's not to find, you know, it's not to make it meet yours. So Sheila would be one of that. And I think with my on a personal level, it would be my aunt, you know, who was just like, again, the advice was not to be like, do this do that. The advice was like, Okay, we're just gonna ride this together, we're just gonna ride this, let's find something that's joyful for ourselves. She was going through, like I said, her husband was sick at home, her business wasn't moving, my partner was going through a lot of stress, because, you know, his son's mother wasn't allowing his son to come and visit and they were experiencing this huge disconnect. You know, it was very stressful for him. And I was pregnant at that time, and supporting him was very difficult. So like, Okay, we all want to do something, but we can't. So what advice do we give? Right? Yeah.

Kit Heintzman 1:07:52

What are some of the ways that you've been taking care of yourself?

Sid Azmi 1:08:01

You know, I finally learned the power of rest, you know, and rest can come in so many different forms. So it's not just sleeping, is not just napping, but it's also doing nothing. You Know, and doing nothing doesn't mean just sit down and do space. Nothing is is is it could mean folding clothes, it just doing mundane. It's I primarily, it's just letting your body rest. And so much of our mental anxieties come from our deprivation, you know, a rest deprivation. And so I've just sort of learned to just rest. And I'm someone who needs to be moving all the time. So I learned how to sew, for example, and that, you know, kept my hands moving. But I was not going anywhere, my mind just circled around the same thought. But also, when you saw you kind of had to focus on the certain little things. So, you know, my mind couldn't travel too far away to craziness. But also, the beauty of the project is there's so many intentional steps that has to happen. So when you apply it to life, it's like, wow, you know, I want to do a PhD. Whoa, whoa, whoa, that's a lot of steps. You know. And so you learn to really break it down and live in the actual stitch by stitch moment. So that's, there's some things that I do I go out to eat. Now. I I've always loved to do this, but I do this at least once a week, I go out and eat on my own. And I love the act of eating on my own because I am experiencing this beautiful meal on my own. I'm not talking to anybody and looking at my phone. I'm judging people secretly. But I'm just in my own company. I don't need to ask about what my partner wants to eat. I don't care I can order three desserts if I want to and I do it sometimes. It's just, it's just an act of real. I do what I want with this one, two hours simple meal, you know. So that's that. But also learning to kind of step away when the moment is hectic is also something I learned to do to take care of myself, as a mom or the type A, who's always coming to like, you know, save somebody, I just learned to be like, No, there's nothing I can do at this point of time, I need to go to my I need to go hide in the closet for like, 10 minutes, and just take a breather, you know, and I curse at all of my children. I curse that my partner for no for being an asshole or whatever. But I let it out in a place where nobody needs to process that. Yes. And I come out much more. Much more able to like deal with stuff. Yeah.

Kit Heintzman 1:10:57

I'm coming to the end of my questions, and they switch gears a little bit. Do you think of COVID-19 as a historic moment?

Sid Azmi 1:11:06

Yes. Yes, I think it for sure. I mean, this is, this is one time I feel like where we human humanity. I mean, it's hard to say that because the disparity in humanity is so different. It's so it's so vast, right? But humanity as I know it in my in my communities, it's like for once we were all in the same shithole together. And there was never a moment where we were all in that same space, like same challenge, you know? And so, yes, I mean, on on so many levels, but I this is how I remember this like, No, we wouldn't we were never in the same shithole together, we have one unique experience where we can all say yes, we've all been there. We got we all have something to say about it. So many things to say about it. But we've been in the same place where like, suddenly the world stopped.

Kit Heintzman 1:12:03

What do you think scholars in the humanities and social sciences, so disciplines like literature and sociology and anthropology, what should we be doing right now to understand the human side of this moment?

Sid Azmi 1:12:18

I think what you're doing is one, right, taking the different stories that people have is one, I would imagine there's going to be a lot of books written about this, just people's experiences. But I again, I would hope for more positive stories than negative ones, because we heard about all of it in the news over and over again, and there has to be some sort of like, panic, right? To get people to move their shit towards the right direction. But also, like, there needs to also be a rejoice in the stillness that took place in the world, you know, and so I don't, I don't know what the intelligent thing to do is. But being able to talk about it, like the way that I did helped me process it, it's going to spark conversations in my, in my circles, I am sure. And little by little, this is going to have some trickling effect in all of us and hopefully, create some sort of like, okay, what is something we want to do better, you know, being where we were at. You know, and where we were at, were so scary and not, and not so scary also, but so scary in its own way, that it's worth thinking, like, you know, that maybe we don't want to come back here again, like, what we what we would, what could we do differently if we were back there again, you know, just to be a better human being, I hope.

Kit Heintzman 1:13:46

I'd like you to imagine speaking to his story, and in the future, someone far enough away that they have no experience of this moment, what would you ask them? Regardless of what they're studying, they come in with a research question, whatever. What would you ask them to remember about this moment, as they go forth with their research?

Sid Azmi 1:14:13

For me, it's like the world stopped. Right? And it was a launching pad for new ideas, new routines, new ways of looking at life. How did people, where do people go from that point? How did the universe change from that point, right. You know, I, I would be curious to learn about all the different opposites that people started doing after that. And I think we see this a lot with patterns of like, where do people move after the pandemic, people started buying homes and smaller places and, you know, changing jobs and stuff like that. And, and that's all great on the outside level, but on an internal level, you know, what do people think about themselves? What do you think about their lives? What do you think about, you know, their forever? When really the clock stopped on all of us? Does it feel like that to people? Am I just the only person who I haven't really had this conversation with too many of my friends, so the pandemic feel for you, you know, like, it just I try to avoid and really big, big questions because I'm irritated when they get to philosophical, but I should be more patient, maybe I'll learn something. Okay.

Kit Heintzman 1:15:38

Those are all of the questions I know how to ask at the moment. So at this point, I just like to thank you for the generosity of your time, and the wisdom of your answers and open up some space, if there's anything you want to share that my questions haven't made room for, please take a take some time and share it.

Sid Azmi 1:16:16

Um, you know, I do want to talk about Please not in terms of a business or in terms of sexuality, but also in terms of like, as a business owner, right. You know, and I guess this could appeal to anybody who has a leadership position or whatever, that and it's just like, you know, when, when a pandemic hit, and when your, your livelihood or the thing that you build is at stake, you know, but then you also take care of other people, like your staff, you know, and there's a part of you that just like, Okay, what about me and not really think about what about them. And I was, I'm really proud to have been able to find a way to sort of accommodate my my stuff and not just be like, Okay, I need to make money to just cover my means, you know, and I operate on like, you know, what, we're all we're all not making money, let's just not all make money together, or let's make whatever I had, I split it with my staff, you know, and whether they appreciate or not, whether they understood what that meant or not, it's not the issue. I think, for me, as a human being, I felt like, Okay, in this moment of like we were in, we were in dire, this is how I chose to react. And this is really important to remind myself, so, you know, just our humanity is so much more important than anything else in the world, whether it's money, whether it's ideas, whether it's our industriousness, you know, I think, coming from New York, sometimes, you know, we have this urgency to like, oh, we must create, oh, certain things define us, we identify ourselves with all these different things, I would like to identify with my own humanity. And I think it's moments like this, you know, without challenges you don't learn resilience, right? So this, these are the things that are important to remember about about oneself. Not so much about being kind. The fact that I, we chose to be we chose to do something, when it was difficult is something that we should remind ourselves in order to encourage ourselves to keep repeating that, if you get what I mean. You know, because of this, yeah. Anyways, so. So that's, that's, there's that.

Sid Azmi 1:18:44

You know, also, I think, you know, keeping certain standards in life, I mean, the pandemic really taught taught me, there are no standards in anything. When I was homeschooling my son, and I was worried that he was playing too many video games with his friends, you know, and suddenly, you know, my therapist said to me, like, Well, how else is he going to socialize? And I'm like, Oh, my God, this was his only way of socializing. And he needed that that was that was more, suddenly video games was great, because that was the only way he could socialize. And he needed that more than his fucking math homework, you know? And so, I'm re adjusting my standards all the time. What is important in life, who is important, like, what what are we all fight arguing about? You know, and if you put now in two weeks view, or in one year's view, is it really important? We hear this repeated to ourselves many, many times, but we don't really think about it as deeply as we should. We really need to being in the being in the moment is really the only response human responsibility that we need to be committed to, I think, because that comes that brings awareness and with awareness you are transacting with the world much more thoughtfully, then just rushing off from now to something. Yeah.

Kit Heintzman 1:20:12

Thank you so much.

Sid Azmi 1:20:14

You're welcome. You're welcome. Thank you for taking the time to take my story. Thank you

Hello, would you please start by stating your name, the date, the time and your location?

Sid Azmi 00:08

My name is Sid Azmi, and it is July 20. And I believe it is 14:07 in Port France, where I am.

Kit Heintzman 00:17

And the year is 2022.

Sid Azmi 00:20

Yes it is

Kit Heintzman 00:23

And do you consent to having this interview recorded, digitally uploaded and publicly released under Creative Commons License attribution noncommercial sharealike?

Sid Azmi 00:33

Yes, I do.

Kit Heintzman 00:35