Item

Setoria James Oral History, 2022/07/18

Title (Dublin Core)

Setoria James Oral History, 2022/07/18

Description (Dublin Core)

Self Description: "My name is Setoria James. I am a Masters Prepared Nurse (MPN). I am currently working in the Jackson area on an oncology unit. I am the president of Black Nurses Rock Metro Jackson chapter of the Black Nurses Rock Foundation."

Some of the things we discussed include:

Working on an ontology unit in a hospital as a master’s prepared nurse.

Being the President of Black Nurses Rock Mississippi chapter.

Black Nurses Rock no longer able to host events for the community–health fairs, donating services to the homeless–and face-to-face chapter meetings.

Nurses supporting other nurses.

Working in a geriatric unit at the beginning of the pandemic, many patients had dementia and Alzeihmer’s.

The special needs of patients with short-term memory disorders during the pandemic and the impact of isolation on them.

Changes in patients’ everyday activities: stopping visitations, single rooms, no collective dining, closing the activities room.

Creating individualized activities.

New safety procedures for incoming patients.

Teaching patients with memory problems cleaning techniques.

Being able to go home to see loved ones while watching patients who didn’t have that same option.

Softening safety restrictions as time went on; delighting in patients’ happiness when they could see family again.

First hearing about COVID impacting northern states and not worrying that it would travel south.

Hospital shifting policies on masks, worries about public perception.

Policy ignoring concerns about exposure to other diseases in the clinic, such as MERCA, after COVID.

Limited access to PPE.

Celebrating birthdays pre-pandemic and during the pandemic.

Mississippi state regulations, public resistance to mask wearing.

Family in healthcare.

Testing policies as work, feeling privileged for access; testing coworkers.

Son in highschool moving from in person to online lessons; difficulty helping son with homework because of differences in education across generations.

Son unable to go to prom, to get a senior portrait or to have a graduation ceremony.

Volunteering at vaccination drives sponsored by churches and integrating other public health services.

Video chatting; new etiquettes about reaching out to friends.

Recently beginning to see friends face to face.

Having even less access to groceries because of the hours working.

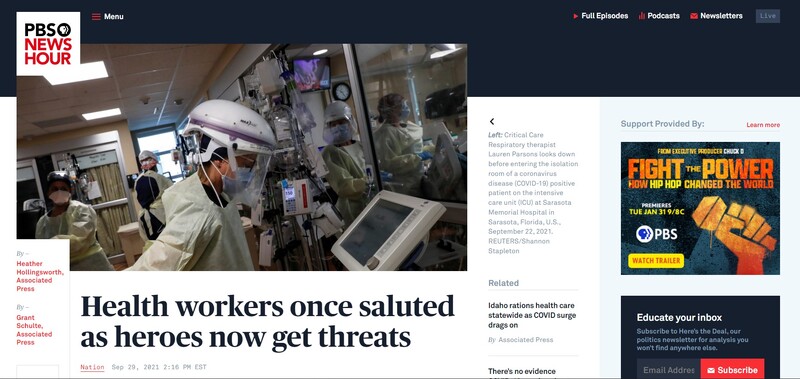

Hearing about the assault of other nurses who were out in public (for example: https://www.pbs.org/newshour/nation/health-workers-once-saluted-as-heroes-now-get-threats).

Becoming a nurse because of the kindness of nurses during childhood.

The importance of funding research for diseases in order to eradicate them.

Going to the gym, nervousness about comorbidities and nervousness about risks in a gym.

The importance of public humanities and engaging the public.

Working on an ontology unit in a hospital as a master’s prepared nurse.

Being the President of Black Nurses Rock Mississippi chapter.

Black Nurses Rock no longer able to host events for the community–health fairs, donating services to the homeless–and face-to-face chapter meetings.

Nurses supporting other nurses.

Working in a geriatric unit at the beginning of the pandemic, many patients had dementia and Alzeihmer’s.

The special needs of patients with short-term memory disorders during the pandemic and the impact of isolation on them.

Changes in patients’ everyday activities: stopping visitations, single rooms, no collective dining, closing the activities room.

Creating individualized activities.

New safety procedures for incoming patients.

Teaching patients with memory problems cleaning techniques.

Being able to go home to see loved ones while watching patients who didn’t have that same option.

Softening safety restrictions as time went on; delighting in patients’ happiness when they could see family again.

First hearing about COVID impacting northern states and not worrying that it would travel south.

Hospital shifting policies on masks, worries about public perception.

Policy ignoring concerns about exposure to other diseases in the clinic, such as MERCA, after COVID.

Limited access to PPE.

Celebrating birthdays pre-pandemic and during the pandemic.

Mississippi state regulations, public resistance to mask wearing.

Family in healthcare.

Testing policies as work, feeling privileged for access; testing coworkers.

Son in highschool moving from in person to online lessons; difficulty helping son with homework because of differences in education across generations.

Son unable to go to prom, to get a senior portrait or to have a graduation ceremony.

Volunteering at vaccination drives sponsored by churches and integrating other public health services.

Video chatting; new etiquettes about reaching out to friends.

Recently beginning to see friends face to face.

Having even less access to groceries because of the hours working.

Hearing about the assault of other nurses who were out in public (for example: https://www.pbs.org/newshour/nation/health-workers-once-saluted-as-heroes-now-get-threats).

Becoming a nurse because of the kindness of nurses during childhood.

The importance of funding research for diseases in order to eradicate them.

Going to the gym, nervousness about comorbidities and nervousness about risks in a gym.

The importance of public humanities and engaging the public.

Recording Date (Dublin Core)

July 18, 2022

Creator (Dublin Core)

Kit Heintzman

Setoria James

Contributor (Dublin Core)

Kit Heintzman

Link (Bibliographic Ontology)

Controlled Vocabulary (Dublin Core)

English

Education--K12

English

Government Federal

English

Government State

English

Health & Wellness

English

Healthcare

English

Home & Family Life

Curator's Tags (Omeka Classic)

hospital

mom

kid

kindness

Contributor's Tags (a true folksonomy) (Friend of a Friend)

Alzeimers

birthdays

Black

cancer

dementia

empathy

family

Fauci

friendship

geriatrics

high school

hope

Jackson

lost graduations

MERCA

Mississippi

motherhood

nurse

PPE

public health

seniors

testing

Collection (Dublin Core)

Black Voices

Date Submitted (Dublin Core)

09/20/2022

Date Modified (Dublin Core)

01/27/2023

Date Created (Dublin Core)

07/18/2022

Interviewer (Bibliographic Ontology)

Kit Heintzman

Interviewee (Bibliographic Ontology)

Setoria James

Location (Omeka Classic)

Clinton

Mississippi

United States of America

Format (Dublin Core)

Audio

Language (Dublin Core)

english

Duration (Omeka Classic)

00:00:57

abstract (Bibliographic Ontology)

Working on an ontology unit in a hospital as a master’s prepared nurse. Being the President of Black Nurses Rock Mississippi chapter. Black Nurses Rock no longer able to host events for the community–health fairs, donating services to the homeless–and face-to-face chapter meetings. Nurses supporting other nurses. Working in a geriatric unit at the beginning of the pandemic, many patients had dementia and Alzeihmer’s. The special needs of patients with short-term memory disorders during the pandemic and the impact of isolation on them. Changes in patients’ everyday activities: stopping visitations, single rooms, no collective dining, closing the activities room. Creating individualized activities. New safety procedures for incoming patients. Teaching patients with memory problems cleaning techniques. Being able to go home to see loved ones while watching patients who didn’t have that same option. Softening safety restrictions as time went on; delighting in patients’ happiness when they could see family again. First hearing about COVID impacting northern states and not worrying that it would travel south. Hospital shifting policies on masks, worries about public perception. Policy ignoring concerns about exposure to other diseases in the clinic, such as MERCA, after COVID. Limited access to PPE. Celebrating birthdays pre-pandemic and during the pandemic. Mississippi state regulations, public resistance to mask wearing. Family in healthcare. Testing policies as work, feeling privileged for access; testing coworkers. Son in highschool moving from in person to online lessons; difficulty helping son with homework because of differences in education across generations. Son unable to go to prom, to get a senior portrait or to have a graduation ceremony. Volunteering at vaccination drives sponsored by churches and integrating other public health services. Video chatting; new etiquettes about reaching out to friends. Recently beginning to see friends face to face. Having even less access to groceries because of the hours working. Hearing about the assault of other nurses who were out in public (for example: https://www.pbs.org/newshour/nation/health-workers-once-saluted-as-heroes-now-get-threats). Becoming a nurse because of the kindness of nurses during childhood. The importance of funding research for diseases in order to eradicate them. Going to the gym, nervousness about comorbidities and nervousness about risks in a gym. The importance of public humanities and engaging the public.

Transcription (Omeka Classic)

Kit Heintzman 00:02

Hello, would you please state your name, the date, the time, and your location?

Setoria James 00:07

Okay, my name is Setoria James. Today is July 18, 2022, and the time is now 2:57pm Central Standard Time.

Kit Heintzman 00:20

And where are you located?

Setoria James 00:22

Oh, I'm sorry. I'm located in Clinton, Mississippi.

Kit Heintzman 00:26

And do you consent to having this interview recorded, digitally uploaded, and publicly released under a Creative Commons license attribution noncommercial Share-alike?

Setoria James 00:36

Yes.

Kit Heintzman 00:38

Thank you so much. Would you please start by just introducing yourself to anyone who might find themselves listening to this? What would you want them to know about you?

Setoria James 00:48

My name is Setoria James. I am a Masters Prepared Nurse (MPN). I am currently working in the Jackson area on an oncology unit. I am the president of Black Nurses Rock Metro Jackson chapter of the Black Nurses Rock Foundation. Oh, I think this [inaudible].

Kit Heintzman 01:13

Would you tell me a story about your life during the pandemic?

Setoria James 01:21

Well, during the pandemic when I first started, I was working on a geriatric behavioral unit. And so, I'm in Mississippi. And when we first heard about it, we had heard about it happening in the northern states. And so, it slowly trickled down to Mississippi. But once they did get the population that I was serving at work, they were had history of dementia and Alzheimer's and stuff like that. So, once it started, we had to stop visitations for the patients that we were taking care of. And it really bothered them because they were not able to see their families and their friends on a regular schedule of visits that we had before the pandemic happened. So that bothered me because you can see a decline in their behavior and in their personalities by them not being able to see their loved ones.

Kit Heintzman 02:22

Would you say more about how it impacted you to be witnessing that happening?

Setoria James 02:29

It was depressing, because of the fact that I was still able to go home to my loved ones and they were not. They were there in that unit, the typical length of stay, be arranged anywhere from one week, up to six months, just depending on the treatment that the patient had going on, and the response to their treatment. And so, dealing with people that have dementia and Alzheimer's, they lose their memory, the short-term part of the memory, but being able to see their loved ones faces, they still remember their loved one faces, they remember their names, you know, their new their daughters, their own sons and nieces, their nephews whoever had taken care of. So, it made me sad, because they were sad, and, and being by me being able to go home, like I said, being able to go home to my loved ones. It was something before the pandemic that I actually took for granted. But once I saw how, you know, in such a short time, everything had changed. In America, those the ones that were stuck in a hospital, but they could not see their loved ones so that that familiarity that they had, of seeing their loved ones, they-they lost it. And even though we were taking care of them, we were, were per se um strangers to them, because we were new faces that they would meet. So, they did not have a history of us with us as they had with their loved ones.

Kit Heintzman 04:08

What was that, like explaining that to the loved ones who wouldn't be able to come? Who was, who was having to do that?

Setoria James 04:16

We asked the nurses; we were having to do that. And also, the social workers and the activity directors that there they were having to explain, but because of their memory loss they wasn't able to get the gist of it. We did have some patients that came in they did not have dementia and Alzheimer’s; they might have had other behavioral or psychological issues going on. So, they knew what was going on in the world. But for the ones that had the dementia, they cannot get a grasp of what was going on or why they couldn't see their loved ones. They were still able to have phone calls with them, but it's different seeing their faces versus how up to a low of one on the phone for that population.

Kit Heintzman 05:07

What was it like working with patients with dementia and Alzheimer's in a moment where there were so many sort of changing safety precautions?

Setoria James 05:19

As far as the changes in the safety precautions, it was okay. I mean, we had to wear a mask and they didn't understand why we had to wear our masks. We had to separate the patients because before they would congregate, in a in a room in a general population room where we call, we call it the day room where we did our activities watching TV stuff like that. So, they didn't understand why they couldn't go in the day room. They couldn't do it. They didn't understand why they couldn't, you know, I'm saying watch TV, why they couldn't play the games and do the activities that we usually do. And like when we have the mask on, we will try to explain you know why we got the mask on. But they just couldn't grasp it.

Kit Heintzman 06:03

Do you remember when you first heard about COVID-19?

Setoria James 06:08

Um, yes, the first thing that I had heard about it was I can't remember what state it was. But I know someone has contracted it in a northern state. They say the hit guy and they had flown across the country somewhere and they were like, at a hospital, but they was doing okay. There was my first memory of hearing about COVID.

Kit Heintzman 06:30

And what were some of your early reactions?

Setoria James 06:35

When I first heard about it, I really didn't think it was as serious as it turned out. To be not to say that the media downplayed it, but just because they didn’t, they had contracted this virus and they were doing okay. You know, I was just like, "Okay, well, somebody caught this virus, they're doing fine." You know, the world still goes on.

Kit Heintzman 07:02

A little curious about what it meant for you to be watching a disease spreading at first in the north, and then seeing how it developed as it came further south.

Setoria James 07:13

Yeah. Now, yeah. Now once it started hitting closer to home, then it will not even before it started paying closer to home. But when you started hearing about more and more people contracting it, and it was spreading very rapidly, then it was like, "Oh, okay, uh oh." You know, this, this, this is something, you know, saying something serious that they can affect anybody. So, when I had started working- Well, I was already working, but like, once, you know, it started becoming more and more popular some people were wearing masks, but um, I higher management did not want us to wear masks before fear of scaring the public. And I remember that I did have a coworker who she had a father that she helped take care of, they had a weakened immune system and so she was like, "Well, I'm going to wear my mask anyway." And it was like, "Well, if you wear masks, you can't use our mask at the hospital." She said that was fine she would purchase her own mask and wear them. And then so a couple of days went by, and it was like, "Well, you can't wear your own mask, because of the views that you know either have on the public as far as affecting the public." But at that time, when they started telling us these things, we had already stopped visitations that was that was at the hospital. So, I really don't understand why they were saying that it how it would affect just the reputation of the hospital or how the public saw us if because we worked on a closed unit. So, there was no outside population coming into visitors. They came in like you know in on certain days at certain times where we had stopped the visitations. So that was kind of a hard thing to have to deal with it work because of what we was hearing about the disease and what you need to do to protect yourself from the disease versus your employer's telling you in spite of what you've heard and what you've learned, this is what you need to do.

Kit Heintzman 09:23

To the extent that you're comfortable sharing, would you say something about your experiences with health and healthcare infrastructure pre pandemic?

Setoria James 09:37

Pre pandemic I worked at a small hospital, and everything ran okay, it ran smoothly. There really wasn't any, like glitches-glitches in the health care system per se. But once the pandemic started you saw things, how quickly things shift. One specific event I remember happening was because of the fact that, you know, you needed your PPE when you was going into these patients rooms, your gloves, your mask, your gowns, and stuff like that. And of course, everything was going in short supply. They-they started us, they wanted us to start not protecting ourselves with other diseases that were contagious. And I didn't understand that because I'm like, if, before the COVID, this this other disease, we treated it, ABC XYZ, why are we changing up the way we treat that disease or protecting ourselves in that disease versus protecting ourselves from COVID? Just because COVID is here. And that bothered me.

Kit Heintzman 10:54

That's really interesting. Could you tell me more about that?

Setoria James 11:01

Um, one of the diseases I would remember specifically, is MRSA, which is a is Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. And it is a bacteria that can get in wounds. And how you protect yourself from that, just because of the germ, it can get on any object that is in a patient's room in a hospital setting. You have to put-put on the same PPE minus the mask, you have to wear your gown, you have to wear your gloves since we take when-when entering that patient's room, because you don't know what is contaminated in the room. And you don't want to get that bacteria or germs on you and then you transfer it to other-other patients that you're taking care of, or your coworkers or your family for that matter. But once the-the COVID virus became more prevalent, they wanted us to stop wearing our PPE for the MRSA bacteria and just treat it like it was just a normal disease. But mind you just because the COVID did, you know that COVID was going on MRSA still had the same it-it still has the same bacteria’s and germs that were just as effective and infectious then as it does during the time of the COVID. And I didn't feel that you needed to protect yourself no different than before the COVID versus while COVID is going on.

Kit Heintzman 12:47

Did your employer give any kind of explanation for that?

Setoria James 12:52

No.

Kit Heintzman 12:54

How did that shift make you feel?

Setoria James 12:58

It-it made me upset because of the simple fact that I feel that I should protect myself as well as protect the other patients that I'm taking care of no different than how I would have done it on any other day.

Kit Heintzman 13:14

Thinking about the world before the pandemic, what was your day to day looking like?

Setoria James 13:20

Before the pandemic day to day routine consists consisted of going to work, taking care of my patients, helping coworkers, coming home. On a typical off day, I would run my own errands, do shopping and pay bills, or spend time with my family celebrating birthdays. Sometimes we would get together and just have like little family a little outing where we might go out to eat or we might go to the movies or something like that. Versus once the pandemic started all of that stopped completely, aside from having to go to work. Still had to go to work. Still had to do shopping, but it was only for necessities, and it wasn't as frequently as it as it was before. I wasn't able to see my family anymore. We would talk on the phone would text on the phone and then we would do like video chats like group video chats for whoever could you know get in on the chat just so we can all just have that sense of togetherness. We will have that.

Kit Heintzman 14:41

Do you remember one of the celebrations of birthdays that happened before the pandemic and what that looked like?

Setoria James 14:47

Oh yes, I didn't realize actually um, my cousin's birthday she had turned 45 and it was It was a tough year for us because she was a twin and her twin had died the previous year. So, this was, you know, her first year without a twin, our first year, you know, have a birthday without them. So, I decided to give her a party, you know, just to kind of cheer up some. And so, I had, it was a surprise party. So, I had told my family about it, we had all you know, just pitched in and what-what everybody was bringing, brought it to the house. And she was she was happy to say, though, to say the least, and surprised that we was able to do that for her.

Kit Heintzman 15:38

And what's does birthday celebrations look like in 2020 after the pandemic hit?

Setoria James 15:45

Um, it really wasn't a celebration, it was just like a regular day. Since the pandemic started. I just started spending time with my family last year. So, it's like we went almost two years without being able to congregate together.

Kit Heintzman 16:09

What were your clients day to day lives looking like pre pandemic?

Setoria James 16:14

Some of the patients that I took care of?

Kit Heintzman 16:18

Yeah.

Setoria James 16:21

You say, a pre pandemic?

Kit Heintzman 16:23

Yes.

Setoria James 16:24

Okay. Well, the most of the population that we serve, they came from either long-term care facilities, or they live at home with their families, or they lived in their apartments and stuff like that. So, when you're in a long-term care facility, you know, you have the other residents that live there also that, you know, they was able to congregate with and be able to see their families. As always, post pandemic, once the clients were once the patients discharged from our facility, and they were going back to their long-term care facilities, because of the COVID. And to try and to decrease the spread of it. Our patients will leave right out facility and go to their long-term care resident, but they will have to go on a closed unit for a isolation period of two weeks to ensure that they don't have the COVID. And they won't be spreading it to the other clients there. I know some of the residents, of course, they have stopped visitation at the long-term care facility. So, what they have started doing was just allowing them to do FaceTime with their family members. So, I know that made them sad. Um, I have had some of the patients that we took care of you know, say, "Well, hey, I haven't seen my daughter in three months." "I haven't seen my sister in six months." They had missed holidays with their families, or they had loved ones that had passed, and they were not able to go to the funerals and they were not able to grieve with their families.

Kit Heintzman 18:06

Did you notice any ways that all of that was impacting the sort of just experience and wellness of your patients?

Setoria James 18:14

Yes, they were not as happy and as cheerful as they usually be. It was like it was a it was it was kind of like it was a gloom over the facility while, while all of this was going on.

Kit Heintzman 18:34

I'd love to hear what you noticed about what was going on in Mississippi more generally, during the pandemic. What did the response from the state look like?

Setoria James 18:47

As far as the response from the state in the in the well-being of the citizens of Mississippi, I don't believe that the response was good. I think the-the guidelines that were set into place that was told to everyone of how to take care of their sales and how to protect ourselves was not taken as serious in Mississippi.

Kit Heintzman 19:22

Do you have a sense of why that was?

Setoria James 19:28

What I can attribute it to a lot of people were upset because they had to wear a mask.

Kit Heintzman 19:40

How did you feel about mask wearing?

Setoria James 19:44

I don't mind it because of the simple fact that it is. You're protecting yourself; you're protecting the people that you come in contact with, and you are protecting your loved ones. But some people felt that their rights were being and violated just because they were asked to put on a mask.

Kit Heintzman 20:08

Oh, sorry. Please continue.

Setoria James 20:10

Okay. And I was just saying that I don't feel this fair because, and in my perspective is like, "Okay, if you don't care enough to protect yourself, cared enough to protect the next person here enough to take to protect your son, your daughter, your sister, your brother, your mother or your father."

Kit Heintzman 20:32

How are you- You've mentioned sort of keeping in touch with family over the phone, how are you feeling about your family over this period of time and their safety?

Setoria James 20:43

I was I was worried about them. I miss them. My- I have another cousin she is in health care and we're very close. So of course, where the unit that I was working on, it was a closed unit and like we tested our patients before we came before-before they were admitted to our unit to make sure they didn't have COVID. So, I kind of feel protected there. But she worked on a general med surg[ery] floor where COVID was more prevalent. So, I was worried about her safety as far as her contracting it. My aunt's, they, and my mother, they're retired. So, they were not like, you know, going, they didn't have to go out into the public.

Kit Heintzman 21:35

What was access to things like testing like?

Setoria James 21:40

For me, the access was okay, because of the closed unit that I worked on, we had to get tested every two weeks, to make sure that that we didn't have it. However, I do know that I've had some friends that, you know, was not as privileged as I was to have access to it. But they was trying to get they had different checkpoints, if you want to say set-up where you can go to get tested, and they will talk about how long the lines were to get tested, or how long they had to stay in line to be able to get tests. And once you got tested, you had to wait two or three days before you got your results back.

Kit Heintzman 22:26

Were you or other staff helping patients with dementia do tests?

Setoria James 22:34

Oh, no, I didn't. Well, sometimes we did test the patients. But I did test my coworkers.

Kit Heintzman 22:42

What was that?

Setoria James 22:45

Um, at first it was it was it was weird. It was scary. But then after we have done it for months on end, it became normalized. A lot of people you know, it's very uncomfortable. So, a lot of people didn't like it, you know, the way that they made it feel but after a while, you know, they were comfortable. "Hey, Setoria time for me to take my tests," and you know, just it just became normalized, it was something to do and being you gonna go back to regular routine.

Kit Heintzman 23:22

I'm curious 2020 had so much going on, that wasn't just a pandemic. What were some of the other issues kind of taking up space in your mind and heart?

Setoria James 23:32

Um, one of the things that bothered me was that was my son's it was his senior year. So, he wasn't able to do prom, wasn't able to do graduation, like all the things that seniors kind of like live for. You know, it's like you go through school this whole time and you're like, okay, your senior year. You have all these activities and stuff that the school has planned, you have activities, plans with your friends, you have trips and everything plan. He wasn't able to do that and so I know that affected him because he didn't. Once the spring break hit came in March, they didn't go back to school after that. So, I kind of felt like he got cheated out of some of the activities that seniors normally get to participate in.

Kit Heintzman 24:25

What was it like for you watching him go through that?

Setoria James 24:29

I was sad. I was hurt. And I was also I felt helpless because there was nothing that I could do about it. But one of the things that I was able to do, although I wasn't able to, like get senior portraits taken for him. I did um, I purchased a camera, and we went out and just took pictures.

Kit Heintzman 24:55

How did he take to the online schooling that he had to transition to what was that like?

Setoria James 25:00

it was tough on him, because the only time he had done a couple of online classes was during the summer. They will have classes that will be like eight weeks long, he would take those. But having to go from go but having to go 100% online, it was some adjusting that he had to get used to. Because he was used to the traditional going to school, having the teacher to explain the things that he didn't understand during the lesson. And it was hard for me because of the way that the way children are taught now has changed significantly from how I was taught. And so, I was not able to help him with the list. And so then again, I felt helpless. I remember, one time, he had some math work that he had to do and I'm not a mathematician, but I do like math. And so, I know the problem that he had, I knew how to get to the answer. But the way that they was teaching him was I was like a deer caught in the headlights, I was totally lost with it. So, my solution was, I'm gonna do the problem that I know, the way I know how to do it, you do the problem, the way you know how to do it. And if we come up with the same answer, we're gonna say you're right. And I don't know if that was the best solution for but that was all that I could come up with at the time.

Kit Heintzman 26:34

What was that like talking to your son about the pandemic?

Setoria James 26:40

It was, it was okay. He is a very educated young man. So, he was watching things that was going on, on the news, at the same time that I was going, you know, saying at the same time that I was watching it. So, he was understanding of what was going on and he knew why he couldn't, you know, do certain things or why things you know, saying were the way they were. But and he tried to be strong about it, but I still felt like, like with activities and stuff like that he was kind of sad in about the way that it was affecting the end of his school year of his high school years.

Kit Heintzman 27:26

How did your social relationship changed during the pandemic?

Setoria James 27:31

Um, I wasn't able to see, my coworkers or my friends couldn't see my coworkers outside of work, and I couldn't see my friends. Because sometimes we would like get together and have get together for lunch, like twice a month or something like that. So, what we would do, we just increased on the phone calls. I really wasn't big on video chatting before the pandemic, but we started video chatting more.

Kit Heintzman 28:06

Tell me about not being so interested in video chatting before and then moving to it during the pandemic.

Setoria James 28:15

Oh, before, it wasn't nothing that I was against. But, um, I wouldn't say that I'm old school, but it was just something that I wasn't used to. So, when I'm calling somebody, I'm calling you and I'm putting the phone to my ear and we're having just a verbal conversation this like what I grew up on. That was all I knew. So that was my norm. So now it's like, okay, well you do your video chat. Then I was like, okay, you have to worry about I guess I don't even know if there's a video chat etiquette. As to say that you like text this person and say, "Hey, are you busy? Can a video chat too?" or, you know, I'm saying stuff like this. So, I don't know what the rules and regulations of that are versus me just picking up the phone and calling somebody and they just, you know, they're able to pick up the phone or they decline the call. So, I'm still I'm still kind of getting I'm still kind of getting used to it. Because I feel like when you video chat if you don't let that person know that you're gonna raise the video chat them you don't know what they have going on and your kind of intruding on them.

Kit Heintzman 29:23

Have you started to see people face to face yet?

Setoria James 29:28

Yes, I have.

Kit Heintzman 29:30

What did it look like when you started to do that again?

Setoria James 29:34

Um, when I well I just started, and it's been kind of okay. I've gone to a couple of dinners a couple of lunches and then I still feel in the back of my mind, you know, I still feel kind of scared. Because okay, you're in the restaurant and of course you have to take your mask off so [inaudible] how close people are as far as the vicinity of where they're sitting, not with the party that you're with, but like the next party and how close people stand to. You know, seeing one another, I pay more attention to that. If someone is coughing constantly or sneezing constantly, they kind of in the back of my mind, I'm like, "Oh, you know, do they have the Coronavirus?" So, I was even though I was out starting to socialize, I was still nervous.

Kit Heintzman 30:42

I'm curious, what does the word health mean to you?

Setoria James 30:47

Um typically, when I think about health, I think about someone being someone being in good health. But I mean, you can be in poor health, you can be in bad health, it comes in different varieties. But when I think about it, I just think about someone being in in good physical and mental health.

Kit Heintzman 31:10

What are some of the things you want for your own health?

Setoria James 31:14

For my own health, I would like to be able to right now I work in exercise. So, I would like to be able to keep continue that and to live a healthier lifestyle so that I can live longer.

Kit Heintzman 31:39

What is the word safety mean to you?

Setoria James 31:43

Um, safety means being able to relax. Being if you're in a place, you, you kind of let your guard down, so to speak, and you are comfortable in your surroundings.

Kit Heintzman 32:04

I know you mentioned a bunch of these already, but just in case, there's anything else. In that sort of tiny confines of safety, for related to COVID, what are some of the things you were doing to keep yourself safer?

Setoria James 32:17

I wasn't going anywhere. I did have to go to like, I have to go to the grocery store. But what I started doing was I will go closer to closing time when it was less populated. I tried a couple of times going early in the morning when it first opened. But um, I learned quickly that that was a no-no, because everybody was at the grocery store as soon as they open. So, I will go close to closing time and even though it was less, it was less populated. But of course, all the shelves were if they weren't wiped clean, the selections were very few of what you can pick, because they were not getting in enough supplies and other supplies that they did have-have in, and I waited to the end of the day. So, I've missed out on you know, a greater selection of things. And then going back to safety, getting gas. I know, I had heard of a story out of state where a nurse had, she was beaten up at the gas pump, because she had on her scrubs. And she was getting gas, but she was the victim, and the perpetrator was like, "Well, you're out here risking our lives because you're out, you know, in the public gettin' gas." And that made me scared because of the simple fact that I work in health care. And I would have to you know, get gas in my vehicle. So, I was nervous about doing that. And I you know; I didn't want that same thing to happen to me.

Kit Heintzman 33:54

That's terrifying.

Setoria James 33:57

It is it-it is and it's sad because of the simple fact that we're putting our own lives at risk, you know, going in and taking care of these patients. But, you know, we put that fear aside because we took an oath to do a certain job but then we're-we're being victimized for you know, for taking care of people that you know, that have the disease. We're not the disease but you know, that had the virus.

Kit Heintzman 34:30

Did you feel valued as a health care worker during this period of time?

Setoria James 34:38

Oh, yeah, I'd be, um, before, maybe not, not so much. But-but after that, it seemed like not to say if people were not appreciative of what you did, they were more verbalized with their appreciation after the pandemic happened.

Kit Heintzman 34:59

Would you tell me on-[inaudible] conversation, that is where someone showed that appreciation to you?

Setoria James 35:07

I had a patient that I was taking care of, had been taking care of them for about two weeks. And I'm I had I had taken care of this patient before. And so, if like, like before the pandemic had happened, then they were readmitted to the hospital. So, you know, we would we had developed the rapport, we will sit down and talk and stuff like that. And so, she, you know, she would just say to me, "Oh, I thank y'all for whatcha y'all do. I thank you for what you do." She's like, "Thank you for taking the time to sit and talk with me." Because during the pandemic, she was not able to see her family and stuff like that. So, because they, you know, I've known her before the pandemic, you know, we-we had become friends and stuff. So, she appreciated me doing that. And then she actually nominated me for the DAISY Award. That's an award that nurses get for just doing, not to say the normal, just kind of like going above and beyond what the expected is for patients.

Kit Heintzman 36:11

That's really beautiful.

Setoria James 36:13

Yes.

Kit Heintzman 36:16

What, what did you notice- so for the patients who were confined to their room, what did they do with their days?

Setoria James 36:27

We would, what-what we started doing was just buying like individual activities, books, magazines, some of them they would like to, like do the color-by-number. So, we started doing things like that, that they can actually do individualized in their rooms.

Kit Heintzman 36:51

How are you feeling about the immediate future?

Setoria James 36:56

The immediate future I am, I am hopeful. I wish that people will start wearing their masks more often now, because of the fact that the numbers are starting to increase. And not to say that we go back to how things were during the height of the pandemic, but I just wish that they will go back to start doing the six feet apart, washing your hands and wearing your mask so we can get these numbers back down.

Kit Heintzman 37:33

How's the how of the policies inside of where you work adopted to the sort of different changes?

Setoria James 37:43

During the height of the pandemic, of course, you know, we had stopped visitations altogether. And then once they did start back having the visitations they were allowed, like two visitors a day. No overnight guests, you would only be able to have those two visitors all day for their periods. So, it had to be one at a time in the room. So, if the visit hours was from 10am to 6pm, however long that one visitor stayed, the next visitor came out that first visitor left and stayed the remainder of that time. So that being it has fast forward to where it is now, you can have overnight guests. You can still now you can have four visitors, and they can all be in your room at the same time. Now, um, and then, like if someone is terminally ill, they can have like, unlimited amount of visitors.

Kit Heintzman 38:50

What was it like first witnessing patients being able to see family members again? So, when things just started opening up.

Setoria James 38:59

Oh, it was it was a joy. It was a delight because you was able to see the patient's faces light up when-when they saw a face that was familiar to them. And so, I mean, I was just overjoyed that they were able to I feel like they was you know, kind of having like, "Okay, this is somebody I know that somebody I'm familiar with." They are truly like happy in this moment. So, it made me happy that they were happy.

Kit Heintzman 39:34

How did you decide to become a nurse?

Setoria James 39:38

I became a nurse because when I was younger, my mom she was diagnosed with cancer. And I remember going to visit her in the hospital. I was young I didn't understand what was you know the severity of her disease, but I do remember the nurses, you know coming in helping her even to have to get up and walk and stuff like that. Because I was used to seeing my mom being strong or superwoman doing any, you know everything. But they had to see her at her weakest point. And she needed help walking and those nurses was coming in to help her walk, help her get dressed, help bathe her. I knew I wanted to have that type of impact on someone else.

Kit Heintzman 40:30

What are some of your hopes for a longer-term future?

Setoria James 40:33

The hopes for the long-term future? I hope that this Coronavirus goes away completely, so that we can go back to, I guess, a world of normalcy or pre pandemic. I hope that happens. And then I hope that we find a cure for cancer. They have drugs that can help, you know, decrease the growth of tumors decrease the spread of the cancer, but I want something that were just eliminated and hopefully, cancer would be eradicated.

Kit Heintzman 41:15

What do you think, would need to change, and happen so that we could find a cure for cancer?

Setoria James 41:24

There needs to be more funds donated towards the research of cancer towards the research of the drugs that are used to treat cancer.

Kit Heintzman 41:40

Who's been supportive of you during the pandemic?

Setoria James 41:46

Everyone that I know my family, my friends, everyone.

Kit Heintzman 41:56

Would you tell me a story about a moment where a family member or friend was supportive, supportive of you?

Setoria James 42:05

I have a friend I really like to call my sister because we have been known each other for over 20 years and she works in the healthcare field. Also, she works in a clinic setting versus me working in a hospital setting. And we were talking on the phone, and I remember one day specifically that you know I just kind of broke down to her telling her about the you know, things that were going on at work and she just gave me some encouraging words. She lifted me up and you know just told me not to give up that we're going to get through this, and things are gonna get better.

Kit Heintzman 42:42

Are things feeling better?

Setoria James 42:44

Yes, they are.

Kit Heintzman 42:48

And what are some of the ways that you've been taking care of yourself?

Setoria James 42:53

Um, have started taking more vitamins to kind of ward off to help and to strengthen my immune system so that I wouldn't be able to fight off the Coronavirus if I became in contact with it. Like I say I had I wasn't going to the gym, but I started going to the gym last year to help just-just to get into better shape so that I won't have no comorbidities that you know if I did catch the Coronavirus that it will be more severe on.

Kit Heintzman 43:33

What did it feel like when you first when into the gym?

Setoria James 43:37

Oh, it was I was nervous because of you know just-just being out in public I was wasn't sure how many people going to be there. That local gym did I do that I have joined they have an app so you can actually see its peak times of when it's crowded. And it's typically crowded like in the evening time when people get off work and stuff like that. So, I go early in the morning where it's not a lot of people there it is a 24-hour game if I don't go early in the morning I'll go late at night when it's like almost empty.

Kit Heintzman 44:22

Did these kinds of changes affect your sort of like sleep schedule?

Setoria James 44:28

Oh, it does. Now when I do go late at night to sleep like when I am off the next day, so I am able to sleep in later but when I do go early in the morning it usually doesn't bother me because-because I get up like about five or six o'clock every morning anyway. So, when I was just starting out, I just start just going to the gym.

Kit Heintzman 44:54

What is some of the impact of the work that you're doing with Black Nurses Rock?

Setoria James 45:05

It impacted it tremendously to the fact that before the pandemic, we were able to do events for the community. We were able to have our face-to-face monthly meetings at our local chapter hall. So once the pandemic started, we stopped the face-to-face meetings, and we started doing phone conferences, and we alternate those with virtual meetings just so we can have that interaction that, you know, we were missing outside of that, outside of the face-to-face meetings. And being as far as it affecting the community, we have done different things for nursing homes. We would donate stuff to the homeless, we were hosting events for-for the community, like health fairs and stuff like that. So, we had to stop doing those our together. Now, once the once they came out with the vaccines, we were able to participate in several COVID vaccination programs that was going on. So, we were slowly able to get back in the community and do things.

Kit Heintzman 46:26

When you were doing phone conferences and virtual conferences, what are some of the things you noticed about the nurses that you were supporting and working with through the organization?

Setoria James 46:40

Oh, well, as far as the phone, the phone conferences, go, they-they are okay, because we still do those, but they just kind of feel more impersonal, impersonable. When-when we was doing the face-to-face ones, it's like we could kind of feed off each other. As far as what, whatever the topic were, we were discussing. And so, by us not having that, um, it kind of just, I guess it made the meetings less personal for me. And also, I would like to see my cohorts, you know, because a lot of the nurses that are in our chapter, we don't work together. But because nursing is our is the thing, we haven't come and you know, we've developed a bond. So, when we have these meetings, you know, you're excited because you get to see your other cohorts, we don't typically see outside of having the meeting or doing something for the community.

Kit Heintzman 47:51

Could you explain a bit about the importance of having an organization like Black Nurses Rock at this moment?

Setoria James 48:01

I think it is important to have, because true enough, we are nurses, but we are only providing skills to our to the population that we serve through our employer. I'm being a nonprofit organization that is community based, we're able to get out and see some of those faces, a lot of the faces that we will not normally see if we were not in the hospital setting.

Kit Heintzman 48:34

You'd mentioned changing a bit after vaccinations came out. What was access to vaccines like where you are?

Setoria James 48:42

Our job offered the vaccines to the employers. Um, we did have it was very few clinics that were given them out. And now the own health departments, they were giving them out where they had these little drive throughs that a lot of states had. And the lines to get those were just as long as the lines that were available to get tested. But when we had these vaccination drives, we had them at different locations in the area. They were sponsored by local churches, they were sponsored by Miss Mississippi, she had one-one day, so the kids were not the kids, but the parents that wanted to come and get the vaccine, they were able to come. And then it's also still able to bring their kids because even though it was the COVID vaccine drive, we still had other benefits that the kids could partake in and one event that I presented. We were still in like blood pressure screenings; we was doing health education. They had a dentist booth set up where the kids can go learn about oral health. They had another table set up where they was given out supplies and stuff like the sanitizer wipes, it was getting back a little individual sanitizers to the public.

Kit Heintzman 50:11

It sounds like there was a lot of awareness that even as COVID was changing, all of these other health needs kept happening.

Setoria James 50:20

Yes, yes, it did. And then that's the thing, just-just because COVID started and happening and it was at the top of the chain, everything else did not stop. Just because COVID happened, you still have to be aware of other things that could be going on with your health.

Kit Heintzman 50:44

What do you think people in the humanities in the social sciences could be helping us do to understand this moment? So, people studying literature or film or sociology? What can we do?

Setoria James 51:03

I think it's doing things like this, doing other documentaries, and making it open for the public to see so they can understand just how real it is because of the simple fact that when COVID was going on, everybody was isolated. You were in your home, and you didn't know what was going on. You don't think, you didn't understand how things were affecting the rest of the world or everyone else that was in the world. So doing things like this and making it open to the public, they can get other people's point of view or perspective of how it was affecting them so they can understand the seriousness and the severity of it. Because even though we are I guess we're not post COVID, but you know, we [inaudible] -do believe that COVID isn't real, and it was a hoax.

Kit Heintzman 52:02

What's been like to hear about people who thought COVID was a hoax or still think it's a hoax?

Setoria James 52:10

Oh, I don't understand that. Because my thing is, if you think it was hoax, you think it's fake. Explain how all these people died.

Kit Heintzman 52:26

What-

Setoria James 52:27

-and the one.

Kit Heintzman 52:28

-no, please.

Setoria James 52:30

Oh, I'll say, and I mean, there's no way that you can explain it regardless of how it got here, who-who brought it here or what brought it here. It is here, it has affected everyone in the world in some form or fashion. So, there is no way that people cannot say that it's not real.

Kit Heintzman 52:54

Where are some of the places that you were getting your information about COVID from?

Setoria James 53:01

I was getting from getting it from my co- cohorts. I was speaking with doctors that was like on the health board for the state of Mississippi. And I was also watching the different news or watching the different broadcast that Dr. Fauci did.

Kit Heintzman 53:18

How did you feel about the news coverage? And how did the news coverage make you feel?

Setoria James 53:22

Um, I felt that it was good news coverage. I was, as far as the information goes, I was excited for it because it was given us some insight of the seriousness, the seriousness of it, the things you can do to protect yourself. But as I was seeing that how they were going around and doing the interviews at the different hospitals and stuff like that it made me it made me very sad and depressed.

Kit Heintzman 53:56

Thinking about your own education, what were some of the things in history that you wish you've learned more about younger?

Setoria James 54:13

There isn't, there isn't anything I can just think of right-right off.

Kit Heintzman 54:24

I'd like you to imagine speaking to some historian in the future, someone far enough away that they didn't live through this and have no lived experience of this moment. What would you want them to remember? What would you want them to be sure that as they go forth with whatever their research question is, what would you want them to at the very least keep in the back of their mind?

Setoria James 54:54

When they're doing their interviews, regardless of what their views are on whatever topic that they are covering whoever they are interviewing, um, just be empathetic to that person, and how that situation affected them.

Kit Heintzman 55:16

What are some of the ways that you've learned about empathy?

Setoria James 55:23

Um, the ways that I've learned about empathy. I believe I have always just been a empathetic person. Because of the, I think that this type of person that I am. When I hear things that is going on with someone, it-it saddens me because I, for one, whatever the situation is, I can't imagine myself in those shoes. And I can only imagine, you know, if and how it is affecting that person. So, what I tried to do is try to help them see a different side to it. And if they are feeling helpless and hopeless, I just tried to give them hope or show them ways that they can overcome the situation that they're going through.

Kit Heintzman 56:14

I want to thank you so, so much for the generosity of your time, and the beauty of your answers and everything you've done. Those are all of the questions I have, or I know how to ask at the moment, but I'd love to open some space if there's anything you want to share that my questions haven't made room for, please say so.

Setoria James 56:38

Oh, no, I don't think so. But I do want to thank you for reaching out to me for conducting this interview and I hope that it is helpful to the population that it reaches. And I think that you are doing a good work.

Kit Heintzman 56:56

Thank you so much.

Setoria James 56:58

Yes, ma'am.

Hello, would you please state your name, the date, the time, and your location?

Setoria James 00:07

Okay, my name is Setoria James. Today is July 18, 2022, and the time is now 2:57pm Central Standard Time.

Kit Heintzman 00:20

And where are you located?

Setoria James 00:22

Oh, I'm sorry. I'm located in Clinton, Mississippi.

Kit Heintzman 00:26

And do you consent to having this interview recorded, digitally uploaded, and publicly released under a Creative Commons license attribution noncommercial Share-alike?

Setoria James 00:36

Yes.

Kit Heintzman 00:38

Thank you so much. Would you please start by just introducing yourself to anyone who might find themselves listening to this? What would you want them to know about you?

Setoria James 00:48

My name is Setoria James. I am a Masters Prepared Nurse (MPN). I am currently working in the Jackson area on an oncology unit. I am the president of Black Nurses Rock Metro Jackson chapter of the Black Nurses Rock Foundation. Oh, I think this [inaudible].

Kit Heintzman 01:13

Would you tell me a story about your life during the pandemic?

Setoria James 01:21

Well, during the pandemic when I first started, I was working on a geriatric behavioral unit. And so, I'm in Mississippi. And when we first heard about it, we had heard about it happening in the northern states. And so, it slowly trickled down to Mississippi. But once they did get the population that I was serving at work, they were had history of dementia and Alzheimer's and stuff like that. So, once it started, we had to stop visitations for the patients that we were taking care of. And it really bothered them because they were not able to see their families and their friends on a regular schedule of visits that we had before the pandemic happened. So that bothered me because you can see a decline in their behavior and in their personalities by them not being able to see their loved ones.

Kit Heintzman 02:22

Would you say more about how it impacted you to be witnessing that happening?

Setoria James 02:29

It was depressing, because of the fact that I was still able to go home to my loved ones and they were not. They were there in that unit, the typical length of stay, be arranged anywhere from one week, up to six months, just depending on the treatment that the patient had going on, and the response to their treatment. And so, dealing with people that have dementia and Alzheimer's, they lose their memory, the short-term part of the memory, but being able to see their loved ones faces, they still remember their loved one faces, they remember their names, you know, their new their daughters, their own sons and nieces, their nephews whoever had taken care of. So, it made me sad, because they were sad, and, and being by me being able to go home, like I said, being able to go home to my loved ones. It was something before the pandemic that I actually took for granted. But once I saw how, you know, in such a short time, everything had changed. In America, those the ones that were stuck in a hospital, but they could not see their loved ones so that that familiarity that they had, of seeing their loved ones, they-they lost it. And even though we were taking care of them, we were, were per se um strangers to them, because we were new faces that they would meet. So, they did not have a history of us with us as they had with their loved ones.

Kit Heintzman 04:08

What was that, like explaining that to the loved ones who wouldn't be able to come? Who was, who was having to do that?

Setoria James 04:16

We asked the nurses; we were having to do that. And also, the social workers and the activity directors that there they were having to explain, but because of their memory loss they wasn't able to get the gist of it. We did have some patients that came in they did not have dementia and Alzheimer’s; they might have had other behavioral or psychological issues going on. So, they knew what was going on in the world. But for the ones that had the dementia, they cannot get a grasp of what was going on or why they couldn't see their loved ones. They were still able to have phone calls with them, but it's different seeing their faces versus how up to a low of one on the phone for that population.

Kit Heintzman 05:07

What was it like working with patients with dementia and Alzheimer's in a moment where there were so many sort of changing safety precautions?

Setoria James 05:19

As far as the changes in the safety precautions, it was okay. I mean, we had to wear a mask and they didn't understand why we had to wear our masks. We had to separate the patients because before they would congregate, in a in a room in a general population room where we call, we call it the day room where we did our activities watching TV stuff like that. So, they didn't understand why they couldn't go in the day room. They couldn't do it. They didn't understand why they couldn't, you know, I'm saying watch TV, why they couldn't play the games and do the activities that we usually do. And like when we have the mask on, we will try to explain you know why we got the mask on. But they just couldn't grasp it.

Kit Heintzman 06:03

Do you remember when you first heard about COVID-19?

Setoria James 06:08

Um, yes, the first thing that I had heard about it was I can't remember what state it was. But I know someone has contracted it in a northern state. They say the hit guy and they had flown across the country somewhere and they were like, at a hospital, but they was doing okay. There was my first memory of hearing about COVID.

Kit Heintzman 06:30

And what were some of your early reactions?

Setoria James 06:35

When I first heard about it, I really didn't think it was as serious as it turned out. To be not to say that the media downplayed it, but just because they didn’t, they had contracted this virus and they were doing okay. You know, I was just like, "Okay, well, somebody caught this virus, they're doing fine." You know, the world still goes on.

Kit Heintzman 07:02

A little curious about what it meant for you to be watching a disease spreading at first in the north, and then seeing how it developed as it came further south.

Setoria James 07:13

Yeah. Now, yeah. Now once it started hitting closer to home, then it will not even before it started paying closer to home. But when you started hearing about more and more people contracting it, and it was spreading very rapidly, then it was like, "Oh, okay, uh oh." You know, this, this, this is something, you know, saying something serious that they can affect anybody. So, when I had started working- Well, I was already working, but like, once, you know, it started becoming more and more popular some people were wearing masks, but um, I higher management did not want us to wear masks before fear of scaring the public. And I remember that I did have a coworker who she had a father that she helped take care of, they had a weakened immune system and so she was like, "Well, I'm going to wear my mask anyway." And it was like, "Well, if you wear masks, you can't use our mask at the hospital." She said that was fine she would purchase her own mask and wear them. And then so a couple of days went by, and it was like, "Well, you can't wear your own mask, because of the views that you know either have on the public as far as affecting the public." But at that time, when they started telling us these things, we had already stopped visitations that was that was at the hospital. So, I really don't understand why they were saying that it how it would affect just the reputation of the hospital or how the public saw us if because we worked on a closed unit. So, there was no outside population coming into visitors. They came in like you know in on certain days at certain times where we had stopped the visitations. So that was kind of a hard thing to have to deal with it work because of what we was hearing about the disease and what you need to do to protect yourself from the disease versus your employer's telling you in spite of what you've heard and what you've learned, this is what you need to do.

Kit Heintzman 09:23

To the extent that you're comfortable sharing, would you say something about your experiences with health and healthcare infrastructure pre pandemic?

Setoria James 09:37

Pre pandemic I worked at a small hospital, and everything ran okay, it ran smoothly. There really wasn't any, like glitches-glitches in the health care system per se. But once the pandemic started you saw things, how quickly things shift. One specific event I remember happening was because of the fact that, you know, you needed your PPE when you was going into these patients rooms, your gloves, your mask, your gowns, and stuff like that. And of course, everything was going in short supply. They-they started us, they wanted us to start not protecting ourselves with other diseases that were contagious. And I didn't understand that because I'm like, if, before the COVID, this this other disease, we treated it, ABC XYZ, why are we changing up the way we treat that disease or protecting ourselves in that disease versus protecting ourselves from COVID? Just because COVID is here. And that bothered me.

Kit Heintzman 10:54

That's really interesting. Could you tell me more about that?

Setoria James 11:01

Um, one of the diseases I would remember specifically, is MRSA, which is a is Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. And it is a bacteria that can get in wounds. And how you protect yourself from that, just because of the germ, it can get on any object that is in a patient's room in a hospital setting. You have to put-put on the same PPE minus the mask, you have to wear your gown, you have to wear your gloves since we take when-when entering that patient's room, because you don't know what is contaminated in the room. And you don't want to get that bacteria or germs on you and then you transfer it to other-other patients that you're taking care of, or your coworkers or your family for that matter. But once the-the COVID virus became more prevalent, they wanted us to stop wearing our PPE for the MRSA bacteria and just treat it like it was just a normal disease. But mind you just because the COVID did, you know that COVID was going on MRSA still had the same it-it still has the same bacteria’s and germs that were just as effective and infectious then as it does during the time of the COVID. And I didn't feel that you needed to protect yourself no different than before the COVID versus while COVID is going on.

Kit Heintzman 12:47

Did your employer give any kind of explanation for that?

Setoria James 12:52

No.

Kit Heintzman 12:54

How did that shift make you feel?

Setoria James 12:58

It-it made me upset because of the simple fact that I feel that I should protect myself as well as protect the other patients that I'm taking care of no different than how I would have done it on any other day.

Kit Heintzman 13:14

Thinking about the world before the pandemic, what was your day to day looking like?

Setoria James 13:20

Before the pandemic day to day routine consists consisted of going to work, taking care of my patients, helping coworkers, coming home. On a typical off day, I would run my own errands, do shopping and pay bills, or spend time with my family celebrating birthdays. Sometimes we would get together and just have like little family a little outing where we might go out to eat or we might go to the movies or something like that. Versus once the pandemic started all of that stopped completely, aside from having to go to work. Still had to go to work. Still had to do shopping, but it was only for necessities, and it wasn't as frequently as it as it was before. I wasn't able to see my family anymore. We would talk on the phone would text on the phone and then we would do like video chats like group video chats for whoever could you know get in on the chat just so we can all just have that sense of togetherness. We will have that.

Kit Heintzman 14:41

Do you remember one of the celebrations of birthdays that happened before the pandemic and what that looked like?

Setoria James 14:47

Oh yes, I didn't realize actually um, my cousin's birthday she had turned 45 and it was It was a tough year for us because she was a twin and her twin had died the previous year. So, this was, you know, her first year without a twin, our first year, you know, have a birthday without them. So, I decided to give her a party, you know, just to kind of cheer up some. And so, I had, it was a surprise party. So, I had told my family about it, we had all you know, just pitched in and what-what everybody was bringing, brought it to the house. And she was she was happy to say, though, to say the least, and surprised that we was able to do that for her.

Kit Heintzman 15:38

And what's does birthday celebrations look like in 2020 after the pandemic hit?

Setoria James 15:45

Um, it really wasn't a celebration, it was just like a regular day. Since the pandemic started. I just started spending time with my family last year. So, it's like we went almost two years without being able to congregate together.

Kit Heintzman 16:09

What were your clients day to day lives looking like pre pandemic?

Setoria James 16:14

Some of the patients that I took care of?

Kit Heintzman 16:18

Yeah.

Setoria James 16:21

You say, a pre pandemic?

Kit Heintzman 16:23

Yes.

Setoria James 16:24

Okay. Well, the most of the population that we serve, they came from either long-term care facilities, or they live at home with their families, or they lived in their apartments and stuff like that. So, when you're in a long-term care facility, you know, you have the other residents that live there also that, you know, they was able to congregate with and be able to see their families. As always, post pandemic, once the clients were once the patients discharged from our facility, and they were going back to their long-term care facilities, because of the COVID. And to try and to decrease the spread of it. Our patients will leave right out facility and go to their long-term care resident, but they will have to go on a closed unit for a isolation period of two weeks to ensure that they don't have the COVID. And they won't be spreading it to the other clients there. I know some of the residents, of course, they have stopped visitation at the long-term care facility. So, what they have started doing was just allowing them to do FaceTime with their family members. So, I know that made them sad. Um, I have had some of the patients that we took care of you know, say, "Well, hey, I haven't seen my daughter in three months." "I haven't seen my sister in six months." They had missed holidays with their families, or they had loved ones that had passed, and they were not able to go to the funerals and they were not able to grieve with their families.

Kit Heintzman 18:06

Did you notice any ways that all of that was impacting the sort of just experience and wellness of your patients?

Setoria James 18:14

Yes, they were not as happy and as cheerful as they usually be. It was like it was a it was it was kind of like it was a gloom over the facility while, while all of this was going on.

Kit Heintzman 18:34

I'd love to hear what you noticed about what was going on in Mississippi more generally, during the pandemic. What did the response from the state look like?

Setoria James 18:47

As far as the response from the state in the in the well-being of the citizens of Mississippi, I don't believe that the response was good. I think the-the guidelines that were set into place that was told to everyone of how to take care of their sales and how to protect ourselves was not taken as serious in Mississippi.

Kit Heintzman 19:22

Do you have a sense of why that was?

Setoria James 19:28

What I can attribute it to a lot of people were upset because they had to wear a mask.

Kit Heintzman 19:40

How did you feel about mask wearing?

Setoria James 19:44

I don't mind it because of the simple fact that it is. You're protecting yourself; you're protecting the people that you come in contact with, and you are protecting your loved ones. But some people felt that their rights were being and violated just because they were asked to put on a mask.

Kit Heintzman 20:08

Oh, sorry. Please continue.

Setoria James 20:10

Okay. And I was just saying that I don't feel this fair because, and in my perspective is like, "Okay, if you don't care enough to protect yourself, cared enough to protect the next person here enough to take to protect your son, your daughter, your sister, your brother, your mother or your father."

Kit Heintzman 20:32

How are you- You've mentioned sort of keeping in touch with family over the phone, how are you feeling about your family over this period of time and their safety?

Setoria James 20:43

I was I was worried about them. I miss them. My- I have another cousin she is in health care and we're very close. So of course, where the unit that I was working on, it was a closed unit and like we tested our patients before we came before-before they were admitted to our unit to make sure they didn't have COVID. So, I kind of feel protected there. But she worked on a general med surg[ery] floor where COVID was more prevalent. So, I was worried about her safety as far as her contracting it. My aunt's, they, and my mother, they're retired. So, they were not like, you know, going, they didn't have to go out into the public.

Kit Heintzman 21:35

What was access to things like testing like?

Setoria James 21:40

For me, the access was okay, because of the closed unit that I worked on, we had to get tested every two weeks, to make sure that that we didn't have it. However, I do know that I've had some friends that, you know, was not as privileged as I was to have access to it. But they was trying to get they had different checkpoints, if you want to say set-up where you can go to get tested, and they will talk about how long the lines were to get tested, or how long they had to stay in line to be able to get tests. And once you got tested, you had to wait two or three days before you got your results back.

Kit Heintzman 22:26

Were you or other staff helping patients with dementia do tests?

Setoria James 22:34

Oh, no, I didn't. Well, sometimes we did test the patients. But I did test my coworkers.

Kit Heintzman 22:42

What was that?

Setoria James 22:45

Um, at first it was it was it was weird. It was scary. But then after we have done it for months on end, it became normalized. A lot of people you know, it's very uncomfortable. So, a lot of people didn't like it, you know, the way that they made it feel but after a while, you know, they were comfortable. "Hey, Setoria time for me to take my tests," and you know, just it just became normalized, it was something to do and being you gonna go back to regular routine.

Kit Heintzman 23:22

I'm curious 2020 had so much going on, that wasn't just a pandemic. What were some of the other issues kind of taking up space in your mind and heart?

Setoria James 23:32

Um, one of the things that bothered me was that was my son's it was his senior year. So, he wasn't able to do prom, wasn't able to do graduation, like all the things that seniors kind of like live for. You know, it's like you go through school this whole time and you're like, okay, your senior year. You have all these activities and stuff that the school has planned, you have activities, plans with your friends, you have trips and everything plan. He wasn't able to do that and so I know that affected him because he didn't. Once the spring break hit came in March, they didn't go back to school after that. So, I kind of felt like he got cheated out of some of the activities that seniors normally get to participate in.

Kit Heintzman 24:25

What was it like for you watching him go through that?

Setoria James 24:29

I was sad. I was hurt. And I was also I felt helpless because there was nothing that I could do about it. But one of the things that I was able to do, although I wasn't able to, like get senior portraits taken for him. I did um, I purchased a camera, and we went out and just took pictures.

Kit Heintzman 24:55

How did he take to the online schooling that he had to transition to what was that like?

Setoria James 25:00

it was tough on him, because the only time he had done a couple of online classes was during the summer. They will have classes that will be like eight weeks long, he would take those. But having to go from go but having to go 100% online, it was some adjusting that he had to get used to. Because he was used to the traditional going to school, having the teacher to explain the things that he didn't understand during the lesson. And it was hard for me because of the way that the way children are taught now has changed significantly from how I was taught. And so, I was not able to help him with the list. And so then again, I felt helpless. I remember, one time, he had some math work that he had to do and I'm not a mathematician, but I do like math. And so, I know the problem that he had, I knew how to get to the answer. But the way that they was teaching him was I was like a deer caught in the headlights, I was totally lost with it. So, my solution was, I'm gonna do the problem that I know, the way I know how to do it, you do the problem, the way you know how to do it. And if we come up with the same answer, we're gonna say you're right. And I don't know if that was the best solution for but that was all that I could come up with at the time.

Kit Heintzman 26:34

What was that like talking to your son about the pandemic?

Setoria James 26:40

It was, it was okay. He is a very educated young man. So, he was watching things that was going on, on the news, at the same time that I was going, you know, saying at the same time that I was watching it. So, he was understanding of what was going on and he knew why he couldn't, you know, do certain things or why things you know, saying were the way they were. But and he tried to be strong about it, but I still felt like, like with activities and stuff like that he was kind of sad in about the way that it was affecting the end of his school year of his high school years.

Kit Heintzman 27:26

How did your social relationship changed during the pandemic?

Setoria James 27:31